|

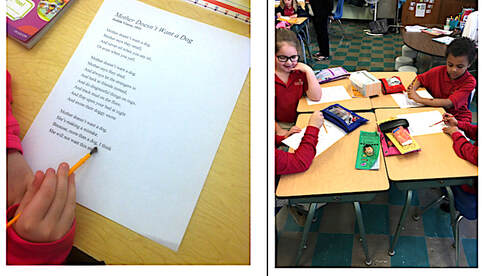

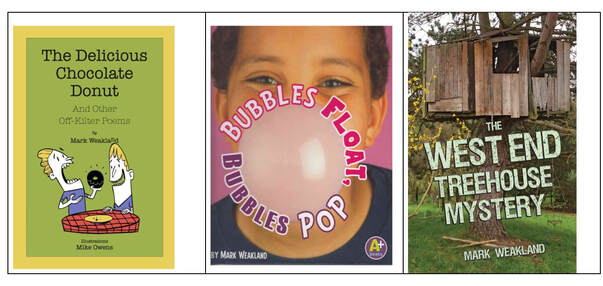

Playful, lyrical, musical, moving, Hopeful, joyful, anguished, blue. Concentrated yet expansive, To the norm they may not hew. Read in classrooms and on stages, Through the ages, old and new. Small but mighty, I applaud them, and Wonder if you laud them, too. -M.W. Why Use Poems? For me, a poem is like a pop-up book, or maybe Yoda and a can of Popeye’s spinach. A poem is minute but mighty, compressing a ton of surprise, wisdom, and fortifying energy into a small space. Efficient and powerful, poems are perfect for teaching, and then having students practice, a wide variety of important literacy elements, including comprehension through close reading, asking and answering questions, genre and author study, vocabulary building, grammar and sentence structure study, phonic-spelling patterns, fluency, and speaking and listening. Additionally, poems are relatively easy to find and manage. They can be used for shared reading, guided reading, and independent reading. Finally, most children find poems engaging and enjoy reading and presenting them. I attribute this to the brevity, rhythm, and rhymes of poems, as well as their ability to evoke a wide variety of feelings and wonderment. When striving readers fluently read and then present poems to others, they gain a real sense of accomplishment and success . All in all, poems are an effective tool for teaching primary grade reading. What follows are places to find them, thoughts on leveling them for differentiated teaching, and a flexible routine for using them to teach a variety of important early reading skills. Where to Find Poems Old school nursery rhymes, traditional poems from years past, and poems from modern and contemporary authors are all at your fingertips, easily found online. Here are three sites to get you started.

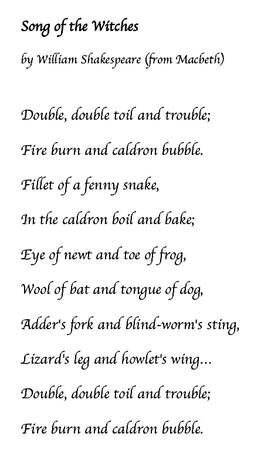

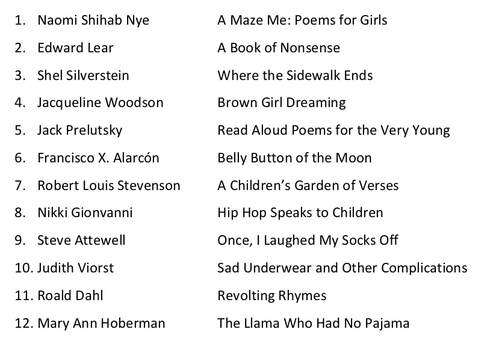

By The Way: Shakespeare for 3rd Graders I found this Renaissance classic in the Poetry Foundation’s children’s section. In mid-October, pass out the witchy-poo pointer fingers, model a good ghoul voice, and let your third graders have at it. By Halloween, some will be clamoring to present! Published poetry collections are the ultimate source of classroom text. Collections often include upwards of 100 or more poems meaning you can generate a collection of appropriate poems for your class in no time. Here’s a list of twelve respected and beloved children’s authors and a poetry collection from each to get you started. Collecting and Storing Poems Between well-stocked websites and comprehensive print collections, you can amass dozens of poems for kids to read in a short amount of time. Storing them as PDFs or word document files allows for easy sharing with other teachers. For use during shared reading time, print poems on poster-sized sheets or present them on SmartBoard slides. For guided and independent reading, copy poems as single sheets. My mother, now retired, presented two poems a week to her first graders. During my years in third grade, I presented about three poems a month. But knowing what I know now (the power of poetry, the myriad ways it can be used), whenever I teach children, I use three or four poems every two weeks. Presenting a number of poems allows you to differentiate for different reading levels, provides numerous possibilities for classroom activities, gives students choices on what they read, and provides options when creating personal poetry anthologies for each student (more on this at the end of this section). Loosely Leveling Poems Leveling poems enables a number of instructional best practices, including providing choice, challenge, and support. Some poems come with a Lexile or grade level. For those that don’t, you can type a poem into a website or word document and generate an ATOS or Flesch-Kinkaid grade level and readability score. But I find these scores are often misleading, sometimes egregiously so. That’s why I roughly determine the appropriateness of a poem for any particular group of students by considering the following:

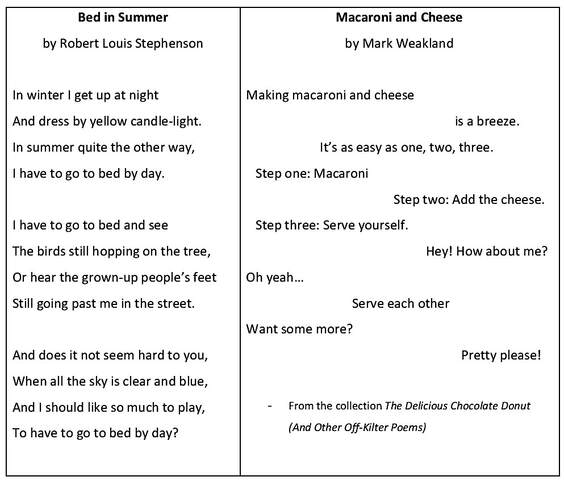

To illustrate, here are two poems I might present to second graders: Comparing these two poems, I see that although Macaroni and Cheese has a complex layout (the poem is written for two or more readers), it has half the number of words of Bed in Summer, fewer phonic patterns, more repeated words, more contemporary language, and relatively simple subject matter. Thus, I think Macaroni and Cheese would be appropriate for readers who need more support. Meanwhile, the Stephenson poem would be appropriate for shared reading because its meaning is more complex, its subject matter more nuanced, it would lead to more questioning and inferring, and some of my striving readers might find its number of words frustrating to read without support. Finally, I would assign the Stephenson poem to my more advanced readers for independent reading, although I would give all my students the choice to read both. Routine for Teaching Reading Skills Through Poems After I have decided on the two or three poems I want to use, I generally follow this 3-day routine to teach a variety of reading skills, from applying comprehension strategies to noticing phonic patterns and re-reading for fluency. First Day (15 t0 20 minutes)

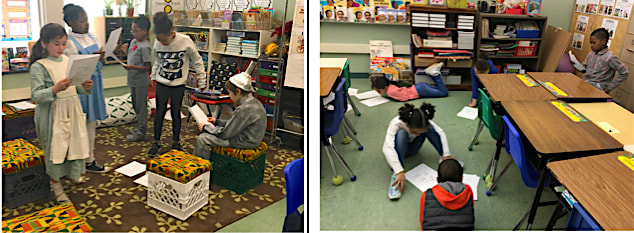

Personal Poetry Anthologies Personal poetry anthologies grow and expand as the months goes by, reflecting a child’s personal preferences. Each poem in the anthology provides an opportunity for students to re-read and build fluency during independent reading time, as well as share their reading with others. Regardless of whether you use the 3-day routine (given previously) or not, put the poems each child has read into a 3-ring binder with his or her name on it. If students are able to do their own 3-hole punching and operate a binder, then so much the better. I give students the option to take a second or even a third poem, each one typically at a different level of difficulty. Thus, after two months, some children will have a dozen poems in their anthology while others may have only four or five. If your budget and/or storage space is limited, you can store poems in a two-pocket folder with or without fasteners. If you don’t use fasteners, I suggest you gradually staple the poems into packets of six to eight poems (so papers don’t go flying if the poems fall out). Illustrating the cover of the poetry book is always a fun and engaging thing to do at home or in the classroom. What can a child can do with her poetry anthology? Here's a list of poetry reading possibilities: During independent reading time, read your poetry anthology...

By The Way: Paintbrush Reading Fluent reading unfolds smoothly, with expression, and in broad brushstrokes of phrasing. To drive the point home, consider putting out a can filled with small paintbrushes. Then allow your students (independently or in small or large groups) to grab a paintbrush and re-read a poem or passage by pulling the brush smoothly below each sentence as it is read. It’s a kinesthetic feedback trick that keeps kids engaged during re-reading. Read like a painter, not…like…a…pointer!

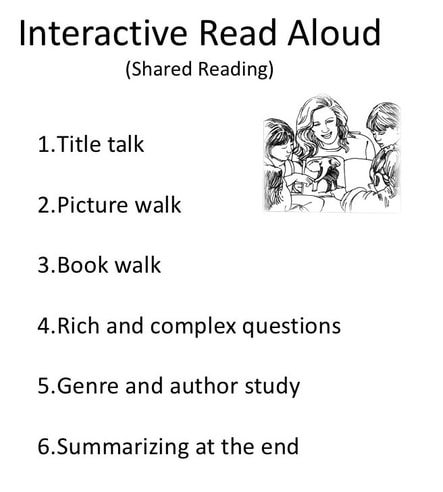

Note for Parents and Teachers To help with National Poetry Month, I’ve put free PDFs and sound files of some of my most popular poems online. Just go to this File Cabinet tab on this website (top of the page, immediately to the right of the blog tab). Then look in the right hand column. There you will find PDF poems and dramatic readings of A Bug, A Bug!, poems for two voices, like Nuh Uh! and Mac & Cheese, and more. The mp3s are super fun readings done by actors Chris Laitta & Biff Baron. According to Kilpatrick (2015) and Scarborough (2001), metacognition, background knowledge, and topical knowledge are components of language comprehension, one of the two variables that describe the Simple View of Reading (the other being word recognition). Other components of this important variable include vocabulary knowledge, grammatical and syntactical knowledge, and self-monitoring. The more a student has of each, the more chance he has of understanding what he has read. Additionally, when the many parts of language comprehension are strong, reading difficulties are less likely to occur. Conversely, if the parts are weak, reading difficulties are more likely to occur. Making meaning is foundational to what it means to read; one’s ability to construct meaning from written text is dependent on knowledge. When language knowledge is combined with the automatic recognition of correctly spelled words, the brain’s reading circuits are connected and the reading process can unfold. In a 2018 overview of the reading process, researchers Anne Castles, Kathleen Rastle, and Kate Nation said this: “When children begin to learn to read, they usually already have relatively sophisticated spoken-language skills, including knowledge of the meaning of many spoken words.” We know, however, that due to differences within families, languages, and social and economic environments, some children come to school with deficits in spoken word (language) knowledge. So, to head off reading difficulties caused by a lack of language comprehension, we have to build language comprehension knowledge of all types, especially background knowledge. It’s well known that background knowledge is essential for reading comprehension (Coppola, S. 2014; O’Reilly, T., Wang, Z., & Sabatini, J., 2019). Just think about it: to construct a mental model of what you are reading, it helps to know something about the text topic. The knowledge can consist of specific information, general information, or both. Regardless, the more a reader knows about any topic, the easier it is for him to read a text, understand it, and retain its information (Neuman, Kaefer, & Pinkham, 2014). Thus, a teacher will find it easier to digest the concepts presented in this blog than a fighter pilot or financial advisor. Interactive read aloud Reading to children is a simple pleasure. When infused with thought-provoking questions and purposefully modeled reading strategies, reading aloud becomes an effective and practical way to build language comprehension. More specifically, interactive read alouds can build background knowledge, topical knowledge, vocabulary knowledge, genre knowledge, and the ability to use metacognition strategies (such as predicting or visualizing). In any give classroom there is a wide range of reading achievement. Thus, reading out loud gives some students a way to access and discuss a book written well above their independent reading level. For other students, a read aloud piques interest in a book they can read independently at a later time, once it is placed on a book-shelf or in a browsing bin. Finally, an interactive read aloud not only generally strengthens components of reading comprehension, but it also provides explicit opportunities to model specific reading skills, such as fluent reading, re-reading, and defining vocabulary from context. It all begins with a carefully chosen quality children’s book, one that is engaging, of any genre, and full of rich vocabulary and concepts. You’ll also need a strong sense of what language comprehension components you want to focus on and an understanding of how to teach them. Let’s tackle this last element first. A series of purposeful activities makes up a typical interactive read aloud. They can include any or all of the following, done for a variety of purposes: Title talk, picture walk, and/or book walk.

Rich and complex practices like an Interactive Read Aloud demand rich and complex study, more than what this blog can provide. Perhaps you’ll want to check out these resource books and material, as they might help you take your instruction to a higher level.

SOURCES

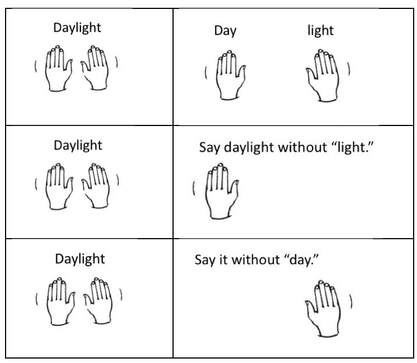

For decades, the educational community has known of the importance of phonological awareness. Many researchers pointed it out prior to 2000 (Bradley, L. & Bryant, 1983, Stanovich, K.E. & Siegel, L.S., 1994, Ehri, L.C., 1998), but it really moved front and center when the National Reading Panel report named it as one of the Five Big Ideas of Reading. The Panel said that teaching phonemic awareness not only helped preschoolers, kindergartners, and 1st graders learn to read, but also helped older readers with reading problems. (NICHD, 2000). Since that time, reading researchers like Sally Shaywitz (2003/2020), Maryanne Wolf (2008), David Share (2011), and Mark Seidenberg (2017) have been highlighting the research on and importance of phonological and phonemic awareness. Here’s Seidenberg talking about it in his book, Language at the Speed of Sight: “For reading scientists, the evidence that the phonological pathway is used in reading and especially important in beginning reading is about as close to conclusive as research on complex human behavior can get” (p. 124). In his 2015 book on preventing and overcoming reading difficulties, David Kilpatrick spotlighted phonological and phonemic awareness within intervention programs, saying that the especially effective ones "…aggressively address and correct students phonological awareness difficulties and teach phonological awareness to an advanced level” (Kilpatrick, 2015). Robust teaching is critical to the development of orthographic mapping: if children cannot analyze and discriminate between the individual sounds of a language, it is very difficult for them to assign letters (alone or in combination) to each sound, and if sound-symbol associations are not mastered, reading and spelling cannot develop. Kilpatrick also mentioned a study that shows how “training in phonological awareness and letter-sound skills reduced the number of struggling readers by 75%” (Shapiro & Solity, 2008). But why wait until students are struggling to teach phonological awareness to an advanced level? To prevent reading difficulties, let’s teach advanced sound analysis skills in regular education classrooms at the Tier I level. What follows are classroom activities that begin moving young students towards advanced phonological awareness. The first focuses on large chunks of sound – syllables. The second has to do with the smallest bits of sound – phonemes. Hands Together, Apart, and Away Advanced phonemic skills include adding, subtracting, and substituting phonemes to make new words out of existing words. Set the stage for this by teaching students to delete or add larger sound chunks such as syllables. One practical way to do this is to practice the deletion of one word in a compound word. Then, practice a more advanced version by replacing the deleted word with another word, thus forming a new compound word. To help children better understand how these deletions and additions work, use hands together, apart, and away. To do this activity with hand motions and preserve “reading left to right,” you’ll need to turn your back to your students and present the back of your hands. With your hands together, thumb touching thumb, say a compound word like “Daylight.” Pull your hands apart and say the compound word as separate words: “Day, light.” Next, put your hands back together and say, “Daylight.” Then, ask your students to say daylight without day. Model taking away your left hand and gently shaking your right. If they don’t know the remaining word, say, “Light.” Ask your students to say daylight without light, taking away your right hand and gently shaking your left. If they don’t know the word, say, “Day.” Here are other words to say as you move your hands to show syllables and syllable deletion:

An advanced form of Hands Together, Apart, and Away is not using hands at all! Bump up to an even higher level by using three syllable words. At this point you will definitely give up the use of your hands to segment syllables (unless you are an octopus). Have students say a three-syllable word like November. Then ask them to say only the first syllable, the last syllable, or the middle. A more advanced version is to ask them to say the word with a syllable deleted. For example, “Say November without the No.” (Vember) Or say, “Say November without the last syllable.” (Novem). Stretch and Zap the Word. Then go beyond! Sound stretching helps students hear the individual sounds of a word. Later they can segment the phonemes more discretely by zapping out the sounds., Use the I Do, We Do, You Do sequence to first model the action and then have students practice.. To stretch a word, tell your students to imagine the word as a big rubber band. Or if you live in western Pennsylvania, tell them to imagine a “gum band.” They’ll know what you mean. Grab hold of either end of the word (make two fists and hold them close to each other in front of you). Then slowly pull your hands away from each other, stretching the word out, holding out the vocalization of each phoneme as you stretch. After the rubber band is stretched as far as it can go and all of the phonemes have been drawn out, snap the band back together with a handclap. When students clap, they say the word. In this way, phonemes are brought back together to make a word. For example, flip would be modeled ffff-llll-iiii-p, (clap) flip! And dream would be d-rrrr-eeee-mmmm, (clap), dream! Some teachers teach this technique as “bubble gum words,” stretching the word out from the mouth as they were stretching a wad of chewed bubble gum. Is this disgusting? Perhaps. But if kids are engaged, do it. We do whatever it takes to get students to learn, right? Second graders stretching a word Add zapping to the stretch routine to help students phonemically segment words and feel that segmentation in their bodies. To model zapping, first say the target word as you make a fist. Next, segment the word into the sounds you hear, pumping your hand and throwing out a finger for each sound you say. For example, the word it gets two pumps. The index finger comes out when you say /i/. The middle finger comes out when you say /t/. Finally, draw your fingers back into a fist, blending the sounds together, and saying the word - it! When giving words, it is important for you to say the word and have your students repeat it with you (I Say, We Say) before the zapping begins. I Say, We Say gives a model of the correct pronunciation of the word prior to sound segmentation and an opportunity to repeat that correct pronunciation. After all, one cannot segment phonemes correctly if the word isn’t pronounced correctly. Here is an example of a teaching routine I ran in classrooms. If I used a total of six or seven words, it took about five minutes. My instruction was direct and explicit, used modeling, and proceeded at a brisk pace. The point was to work in lots of practice so the kids could master the technique. Once mastered, children can use zapping as an independent strategy for spelling and reading unknown monosyllabic words. In this lesson, we’ll imagine the teacher is working with a group of second graders on the r-controlled syllable.

With short bursts of repeated practice distributed over time, students can master the art of stretching and zapping in just a few weeks.Then they will be ready for more advanced work: sound identification and sound deletion. For example, after students have segmented stork as /s/ /t/ /or/ /k/, ask, "What is the first sound?" The answer should be /s/. Then ask, "What is the final sound?" and "What is r-controlled sound?" The answers are /k/ and /or/. Sound identification is a more advanced form of phonemic analysis than simple segmentation.

Finally, ask students to delete a sound. For example, and once again using stork as the target word, ask your students to "Say stork without the /s/." The correct response is /tork/. Then ask them to "Say stork without the /k/." The correct response is /stor/. Sound deletion activities are a great way to build advanced phonemic awareness. They also have the added benefit of being sensitive to some types of reading difficulties. This means that sound deletion tasks can provide clues as to why a child is having a difficult time learning to read and write, and here I am thinking of students who have dyslexia due to phonological processing impairments. One last thing: if you prefer to use a program, and you are looking for effective, low-cost options, here are three excellent resources:

SOURCES

“No single truth does not mean no truth.” - Iain McGilchrist It’s the first month of the first year of a new decade and I’m ready to tackle new blog postings. This month I’ll start with thoughts on the truths of reading instruction. In upcoming weeks and months, I’ll post activities, routines, and strategies that flow from these truths. From Research to Practice In our modern era, the definition of truth has become increasingly open to debate. Nowadays, there’s a lot of emphasis on personal truth, truth is equated with authenticity. and your truth might not be my truth. In many instances, truth, like beauty, now resides in the eye of the beholder. Historically, however, the word’s definition was rooted in objective facts, observable phenomena, and measurable standards. Because I believe teaching is the melding of art and science, I am going to use truth as defined by facts, phenomena, and agreed upon standards as my starting point. When viewed in light of reading theory and classroom instruction, Iain McGilchrist’s opening quote on truth speaks to the idea that there are many ways to teach reading and writing, and that no single way of instructing children is best. But the quote is also a reminder that no single best way does not mean no best ways at all. In fact, when it comes to helping children become competent readers, some instructional practices are better than others, and by better I mean more effective. Reading researchers know a lot about how kids learn to read and write and the theories of reading and writing processes (as well as instruction) developed by researches are increasingly stable and predictive. Here, for example, are two recent statements from well-known literacy experts. Both put a point on what others have been saying for decades:

On the one hand, statements such as these can be helpful because they point to truths about reading instruction. On the other hand, these types of statements provide little insight into what teachers can actually do in a classroom on a Monday morning. A lack of practical classroom activities built on scientific truths may be one reason the field of teaching still isn’t moving large numbers of students to the point of proficient reading (NAEP, 2017). There are other reasons, of course. Societal ills, such as drug abuse, poverty, and a weak social safety net for children, negatively impact student learning in a big way. Also, uninformed or ideological thinking among teachers and professors of education can lead to a dearth of effective instruction. A 2009 study in the Journal of Learning Disabilities found many teacher preparation programs lacked attention to concepts put forth by the National Reading Panel in 2000 . Fast forward seven years and things weren’t much better. Here’s what a 2016 Journal of Childhood & Developmental Disorders article said about one important area of reading and instruction: “Although the Science of Reading provides considerable information with regard to the nature of dyslexia, its evaluation and remediation, there is a history of ignorance, complacency and resistance in colleges of education with regard to disseminating this critical information to pre-service teachers.” One of my interests is giving teachers instructional practices, rooted in a stable theory of how reading arises in the brain, that lead to lots of learning in phonologic, orthographic, and language comprehension knowledge. These practices include teaching decoding and encoding (sometimes a lot of it) as well as metacognition and meaning (sometimes a lot of it). The parenthetical comments “sometimes a lot of it” are important because I believe reading instruction shouldn’t be balanced at all times for all kids. There are times to focus on one skill set more than another. For example, capable readers who are ready to explore genre, authors’ purpose, and metacognition strategies can be given these and for these children, pattern work and re-reading for fluency will take a back seat. Meanwhile, students still trying to “break the code,” need higher doses of encoding, decoding, and re-reading for fluency. Of course we don’t want to go overboard. Reading is always about meaning, and engaging children’s literature and comprehension activities should always have a seat at the table. The Components of Reading Success I think of effective reading instruction, grades K-2, in terms of four basic components. Because each component reinforces the other, the effect that is greater than the sum of the parts, and literacy instruction works best when all are in place.

Each of these components can be taught through any number of techniques, activities, routines, and/or strategies, which I collectively call practices. In upcoming blogs I’ll highlight ones useful for teaching low achieving readers as well as typically achieving ones, effective with young children and older children, and applicable in classroom instruction as well as specialized interventions. Also, none of the practices will be programmatic, which means they can be integrated (to varying degrees) into any number of instructional frameworks, from balanced literacy and Reader’s Workshop to basal reading programs such as Reading Street and Wonders. In my next blog, I’ll start with two ideas for building language comprehension.

Preventing Reading Difficulties When appropriate instruction and intervention are provided, most students with literacy problems in their early years do not have long-term difficulties. This is wonderful news! If we identify areas of concern early and instruct specifically and effectively, serious reading difficulties might never arise. Some research states that interventions can greatly reduce the number of children with continuing difficulties in reading, perhaps even below 2% (Torgesen, 2003; Vellutino et al., 2000). So, here’s to 2020 and to looking at instructional practices that provide foundational reading skills and help prevent reading difficulties from occurring. Thank you for joining me in the important action of teaching children to read! SOURCES

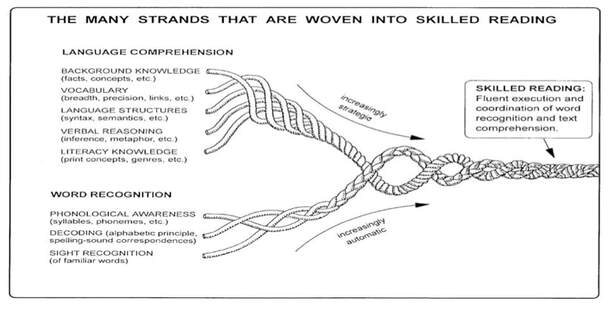

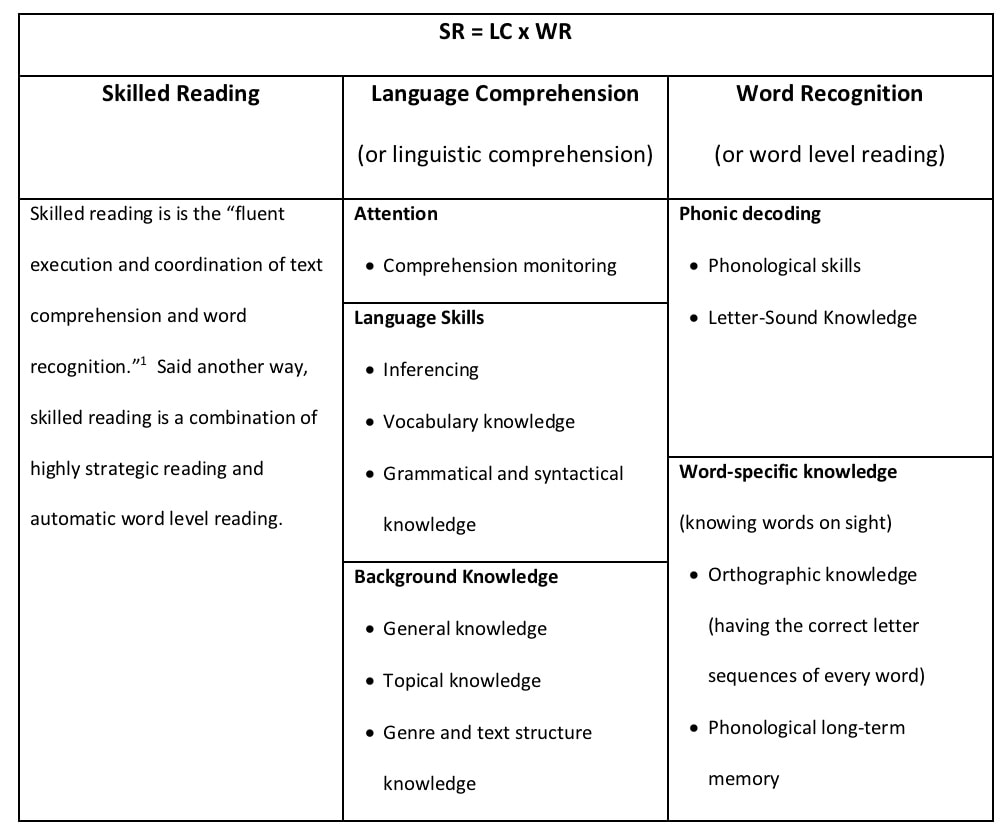

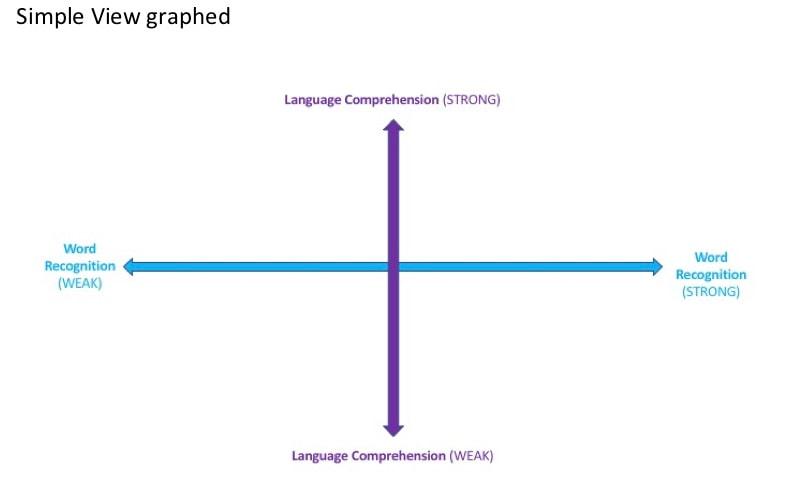

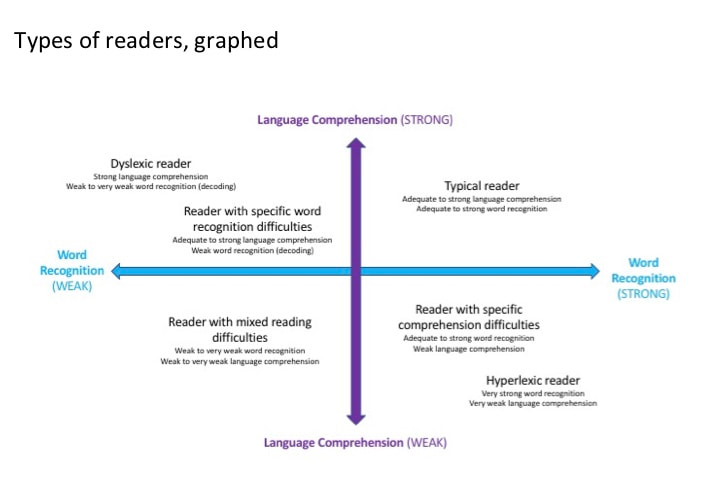

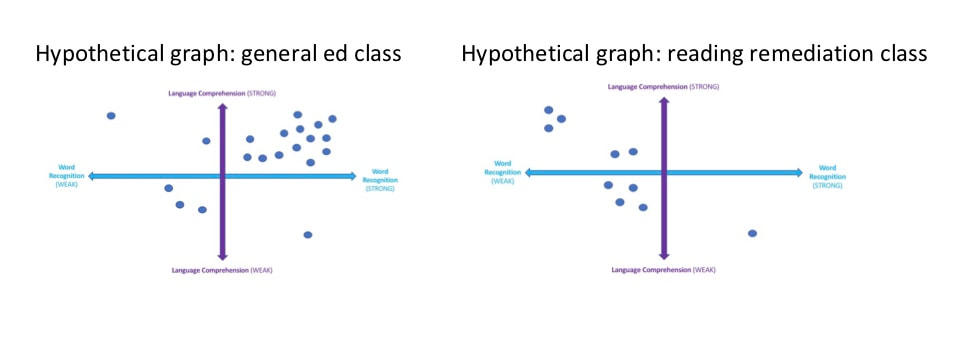

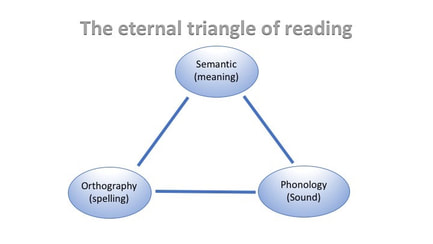

Reading involves identifying letters, mastering sound-letter associations, combining letters into phonic “chunks,” learning word meanings, reading through every word on a page, making connections between text ideas, understanding genre, employing strategies to stay on task, and much more. In other words, reading is complex! Are there simple ways of entering into the complex world of reading theory? For sure. In earlier blogs, I presented the Eternal Triangle, which describes the foundations of the reading process through three terms: semantics, orthography, and phonology. Amazingly, these terms can be condensed even further. The Simple View of Reading The formula that is the Simple View of Reading was put forth more than 30 years ago in a seminal article entitled “Decoding, Reading, and Reading Disability.” Then, reading researchers Philip Gugh and William Tunmer proposed the following equation: R = D x C. In other words, “…reading equals the product of decoding and comprehension” Over time, this elegantly described process of reading has come to be understood in increasingly nuanced ways. Thus, the formula’s terms and definitions have changed a bit. For example, shortly after the National Reading Panel released its report in 2000, Dr. Hollis Scarborough[ii] presented the Simple View of Reading as a braided rope, constructed of two main strands, each consisting of numerous threads. Anchoring her innovate and illuminating graphic is a slightly-tweaked formula: SR = LC x WR. Here SR is skilled reading, LC is language comprehension, and WR is word recognition. Later, in 2015, David Kilpatrick wrote the Simple View’s equation as R = LC x D, where LC equals linguistic comprehension and D is actually word-level reading[iii]. He then broke down the two variables – linguistic comprehension and word-level reading - into components and sub-components, all of which overlap and interact in complex and interesting ways. The chart below provides a synthesis and a summary of most, but not all, of the components and subcomponents of the Simple View of Reading according to Scarborough and Kilpatrick. When I look at the chart, I realize the Simple View of Reading is really not so simple! Nonetheless, Scarborough’s and Kilpatrick’s organizational schemes help me in my quest to understand why many children experience varying degrees of difficulty while learning to read. Because narrowly defined skills influence the development of broader ones, small problems often beget big ones. For example, if a child fails to develop strong phonological skills, especially in the area of phoneme analysis, her ability to map letters onto sounds is diminished. In turn, word-level reading is diminished and this ultimately leads to deficits in reading comprehension. Likewise, if a child lacks knowledge about words (vocabulary knowledge) and the world (background knowledge), her language comprehension is diminished. In the end, this leads to deficits in reading comprehension. I love the Simple View of Reading for many reasons. First, research has widely supported the ideas inherent in the model. Second, the Simple View reflects the same reading process described by the Eternal Triangle. The two inform one another. Third, the equation is a clean, straightforward way for teachers like me to enter the intricate world of reading theory, including how reading works, how reading can be assessed, and how reading can be instructed. Fourth, the Simple View helps me to quickly conceptualize and organize my classroom reading practices so they prevent reading difficulties from happening in the first place. To Understand Reading Difficulties, Graph the Simple View The Simple View of Reading describes the constant interaction between two dynamic processes: language comprehension and word recognition. Graphing the two processes makes this interaction even easier to see. To create a graph, first think of a child. Then think of how much difficulty or ease that child has with each process. This difficulty or ease can be represented as a specific point on each process line. For instance, a point on the far left end of the word recognition line would represent a student who is experiencing great difficulty in decoding. Meanwhile, a point somewhere towards the middle of the line shows a child who finds decoding to be only somewhat difficult (or somewhat easy), and a point on the far right denotes a student who has automatic and effortless word recognition.The same holds true for any child’s position on the language comprehension line. Next, show the Simple View’s two processes as two perpendicular intersecting lines. Viola! We now have a graph with quadrants of reading variability. We can use these four quadrants to frame our observations and assessments of any child’s reading behaviors. [iv][v] [vi] Any reader not in the “typical reader” quadrant can be said to have some type of regularly occurring reading difficulty.The figure below shows and defines categories of readers as described by their position in the quadrants. Of course, assessments helps us to pinpoint a reader on the graph. Information from reading words lists, running records, and oral reading fluency probes give information on word recognition. Assessments that measure vocabulary, metacognition skills, and background knowledge give us information on language comprehension. Plotting a reader as a point on the graph gives a student’s general reading profile or category[vii]. Plotting many students gives a scatter plot that generally describes the make up of a classroom or roster. Below are scatter plots from a hypothetical general education classroom (20 students) and a reading remediation roster (10 students). The second graph shows one student with hyperlexia, three students with dyslexia, two students who are having some difficulty with word recognition, and four students who have deficits (to varying degrees) in both word recognition and language comprehension. Keep in mind that reading comprehension is strong only when a reader has strength in both variables. Conversely, reading comprehension is always negatively affected by a weakness in either variable. Thus, even though a boy has a high degree of language comprehension, he could still show a low degree of reading comprehension. In this case, a lack of word recognition (decoding) keeps the child from accessing meaning. If you were to read this sentence to this boy – “A volcanic eruption was imminent” – he’d know just what it meant. But if you asked him to read it independently, he would struggle through the words volcanic, eruption, and imminent, and in the end, might have no idea of the sentence’s meaning. The End Goal In earlier blog’s, I’ve described the reading process in terms of the Eternal Triangle. This time it’s been The Simple View of Reading. When I think of how the two inform one another, my takeaway is this: successful and happy readers effortlessly recognize words as they read AND exist in a constant state of language comprehension and meaning-making. Conversely, unsuccessful readers have a limited ability to break the code, cannot effortlessly recognize words as they read, and/or lack the skills and knowledge that generate high amounts of language comprehension. So, as a teacher of reading, where do I put my instructional eggs? Into two baskets, of course: practices that help kids “break the code" and promote effortless word recognition, and practices that develop a child’s ability to make meaning and comprehend language while reading. Reading is a complex process. Many things can go wrong as teachers teach it and learners learn it. Still, reading difficulties can be prevented. One way to accomplish this goal is to employ general classroom instruction that offer all children many opportunities to learn and practice important skills while simultaneously supporting striving readers and writers. In upcoming blogs, I’ll share examples of this type of instruction. Sources

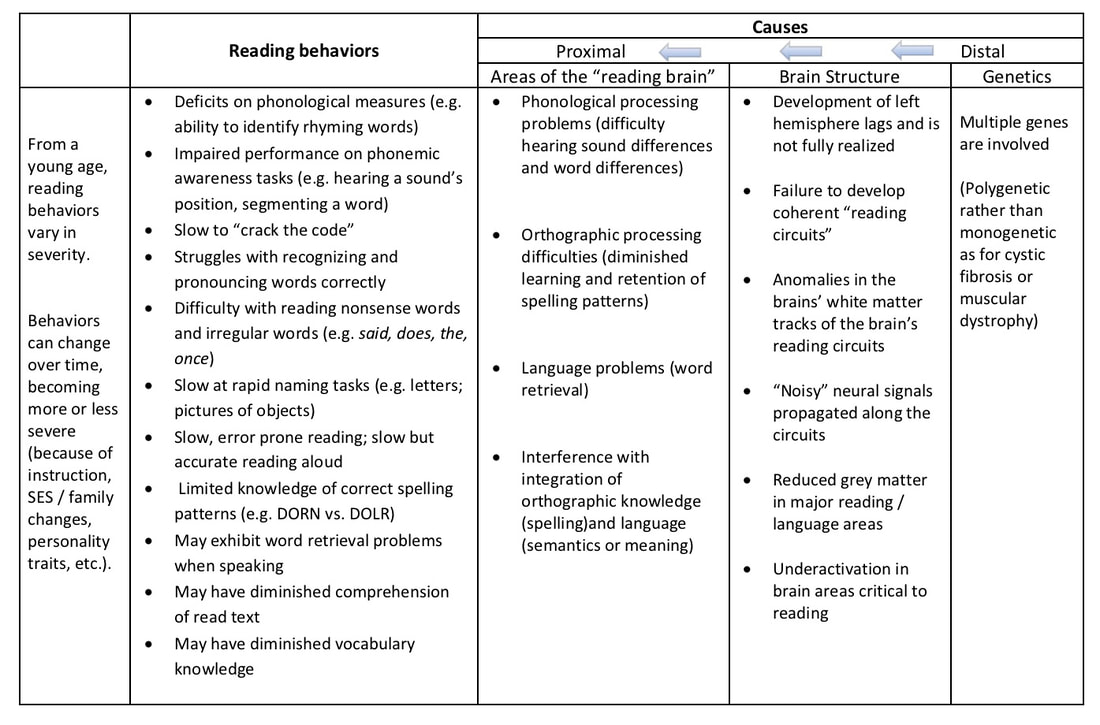

Recently I was talking to an editor, discussing an idea for a teacher resource book. “I think you should include information on what a reading difficulty is,” she said. “Good idea,” I thought. “No problem.” Later, after hours of pouring over articles and studies on reading difficulties, disabilities, and disorders, my thought was, “Yeah, that was easy for you to say!” Reading, and learning to read, is a difficult for many children. Some experts say up to 20% of our nation’s kids experience reading difficulties. Others, like Dr. Kathryn Drummond, put a number on the problem: “One estimate is that about 10 million children have difficulties learning to read.” Meanwhile, reports from the National Assessment of Educational Progress show that about one-third of America’s fourth graders are reading below a Basic level. According to the NAEP, these children are having a difficult time reading. (Sources below). The good news is that reading difficulties can be prevented and even overcome. Dr. David Kilpatrick, reading expert and professor of psychology, says research studies indicate that the the number of struggling readers can be reduced by 70-80% or more. Others are even more optimistic. The International Literacy Association, citing the research of Frank Vellutino and Joe Torgesson, asserts that appropriate interventions can “… reduce the number of children with continuing difficulties in reading to below 2% of the population." But what exactly is a reading difficulty? Who decides how to define them? Are there different types? If yes, what do they look like and what causes them? Behaviors Before we consider difficulties in terms of reading behaviors, let’s look at non-reading behaviors, which are also important to note. When you scan your classroom, it’s easy to spot the kids who enjoy reading. They willingly tackle text, independently reading for long periods of time, focusing intently as they read through paragraphs and pages. When they read aloud their fluency is strong. After reading, they happily discuss their thoughts, feelings, and opinions about all they have read. All in all, these children enjoy the act of reading. Other children are not so involved and contented. They may avoid books. Some don’t want to read in front of their classmates. Others may actively try to avoid the task. Avoidance behaviors include acting silly, asking to go to the bathroom or nurse, or becoming painfully shy. When it comes to the actual act of reading, as well as spelling and writing, struggling readers exhibit a wide range of behaviors. Each can have a differing degree of severity. The list below, based on the work of Seidenberg, Kilpatrick, and Wolf, gives examples:

Some children show only a few signs of struggle. Others show many. Some students have only mild impairments. Others have severe. For some, reading difficulties are easily corrected and short lived. But other children have problems that are tenacious, long-lasting, and debilitating. Difficulty vs. disability Behind each observable reading difficulty is an underlying reading weakness. In other words, there is a reason, or a combination of reasons, why a child makes spelling errors, fails to accurately decode words, cannot remember what was read, fails to read fluently, or doesn’t understand the meaning of the text. Like the behaviors themselves, the reasons for reading difficulties are varied and exist in varying degrees of severity. Some students may have a reading-related disability or disorder. Often these conditions are rooted in biology. Most, like dyslexia, manifest as a group of specific reading difficulties that are moderate to severe in their impact, persist over time, and are not caused by environmental factors such as economic or environmental disadvantages, a lack of reading instruction, or difficulties speaking and/or understanding the language. For special education purposes, a struggling reader might be identified with a specific learning disability, an intellectual disability, or a speech-language impairment. Meanwhile, over in the clinical realm, a child might be diagnosed with dyslexia or dysgraphia. Each of these is a specific learning disorder, according to the American Psychiatric Association. For example, dyslexia is a learning disorder that is neurodevelopmental in nature and begins at school-age. Case Studies To illustrate a reading difficulty severe enough to be labeled a disability, I offer Robert (not his real name). Teachers were concerned about Robert even when he was in kindergarten. He was always a happy child, friendly and outgoing, and he didn’t shy away from reading. But learning to read was chronically difficult for him. He was slow to recall the names of letters. Spelling words using sounds-letter associations was difficult for him, as were generating rhyming words and segmenting the individual sounds of CVC words. In first grade, his progress through the guided reading levels was slow. Because he wasn’t learning through the general classroom instruction, Robert was given instruction in an intervention group twice a week for 25 minutes. By the end of 1st grade, Robert was behind in his reading. In second grade, Robert received instruction in a co-taught classroom staffed by a general education teacher and a reading specialist. The class size was limited to 16 students. Still, Robert only made 0.3 to 0.5 year’s-worth of growth on various reading assessments.. In third grade, Robert was once again placed in a classroom with low student numbers and two teachers. This time his program included more guided reading, more direct and explicit instruction, more phonics and spelling practice, more guided writing, and a class-wide behavior reinforcement program. Robert made more progress than before (0.8 year’s-worth of growth) but it still wasn’t enough to allow him to reach important reading benchmarks or catch up with other students. At the end of 3rd grade, Robert was referred to the school psychologist who, after giving a battery of assessments, determined he had a specific learning disability. In contrast with Robert, who had a diagnosed learning disability, I offer my niece Morgan, who graciously gave me the go ahead to write about her. In kindergarten and first grade Morgan was a typically achieving student, neither struggling nor high flying. But her reading took a turn for the worse in 2nd grade. At the beginning of the school year she came down with mononucleosis. For almost seven weeks, she was mostly at home. Thanksgiving and Christmas breaks added to her days out of school. By January, she was experiencing reading difficulties. Truth be told, Morgan’s school was ill-equipped to help children in her class who were falling behind but weren’t in special education. I know this because I did volunteer work there. Second grade instruction was basal-based, mostly whole group, with lots of workbook assignments. There was a dearth of direct and explicit instruction, little differentiated instruction, and no guided reading. Additionally, non-special ed reading intervention groups met twice a week for 30 minutes, and after subtracting the minutes it took kids to transition, the time left for instruction was more like 20 minutes. Through January, Morgan fell further behind. At an early-February parent-teacher meeting, Morgan’s mother was shown her daughter’s low reading scores. The homeroom teacher suggested Morgan be assessed for the special education program. Morgan’s mom was dead-set against that option. Instead, she asked me to help. Before I began tutoring my niece, I listened to her read. It was slow, hesitant and full of errors. Morgan failed to understand portions of the stories she read. She didn’t engage in much self-monitoring or employ meta-cognition strategies. And when I gave her a phonics inventory and spelling inventory, it was obvious she lacked foundational decoding and encoding skills. Over the next four months, I tutored Morgan two to three times a week for 60 to 75 minutes. She studied phonic patterns, built words with the patterns, and read word lists. She wrote and practiced applying sounds and letters, patterns, and other strategies while spelling. She worked on fluency through repeated readings of passages and I made sure that she looked at every word and read through the entire word using decoding strategies. She read for an extended amount of time in books that were on her independent and instructional levels and we discussed how she could fix up her mistakes, as well as make connections, visualize, and ask and answer questions. And we ended the session with my reading a bit rom a chapter book she had picked. By early June, Morgan was back on track. I talked to her mom about making sure she read a lot over the summer and Morgan did this. I did a bit of tutoring over the summer, too. Since then, there have been no major problems. Morgan recently told me she has to work extra hard to achieve in school, probably harder than most students, and she’s not much of a recreational reader. Nonetheless, Morgan went on to get her bachelor’s degree. Now she’s working on her master’s degree and pulling a 4.0. Conclusion Both Morgan and Robert experienced reading difficulties. Robert’s were severe and long lasting. Morgan’s were not. Both students, however, were helped by specific instructional practices. And in Morgan’s case, specific practices prevented further problems. All striving readers require instruction that speaks to the underlying causes of the problems. In my next blog I’ll use the Simple View of Reading to go “behind the scenes” and examine the actual causes of many reading difficulties. Sources:

You may have heard that “In primary grades, kids learn to read, and in upper grades, kids read to learn.” It’s a cleverly constructed saying, but it’s not true. Children in all grades do both. So, if you’re a middle school teacher focusing on using text to convey information (reading to learn), you can also help your students learn to read. One practical way to help middle grades students improve their reading skills is to provide direct and explicit spelling instruction. Did you know spelling is for reading? It’s true! Spelling instruction helps students store the correct letter sequences of words in their “brain dictionary.” Once a word is stored, it is available for reading as well as for writing. To read, children (and adults) make use of the sounds, meanings, and spellings of words resident in their brains. The three elements – sound, meaning, and spelling – interconnect through brain circuits that bring about reading. Morphology is the fancy word for studying the meaning-making parts of language. Younger children will be exposed to simple letters, like the letter “s,” which in the word forks means more than one. For middle grades students, one logical way to connect spelling to sound and meaning is through syllables, the “chunks” of spoken and written language. Spoken or “audiated” syllables are encoded when students spell words in writing. Conversely, written syllables are decoded into sound during reading. In the upper grades, syllables often take the form of prefixes, suffixes, and Greek and Latin roots. Middle school kids see them all the time in English, History, Science, and Geography. When you help students understand the meaning of syllables, be they affixes or roots, you connect spelling instruction to reading and vocabulary. Wow – talk about synergistic, powerful teaching! Common chunks taught by category What spelling syllables should be taught in middle school? Here are three suggestions. The first two are based on fascinating work done by reading researchers Patrick Manyak, James Baumann, and Ann-Margaret Manyak. The third is featured in my spelling resource book, Super Speller Starter Sets.

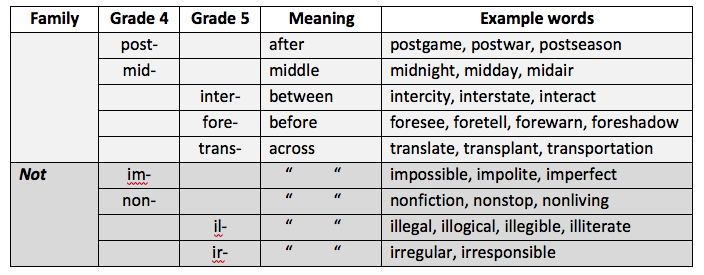

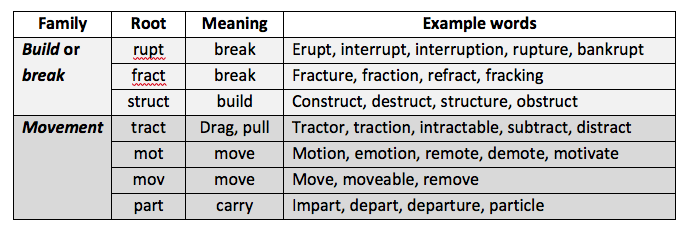

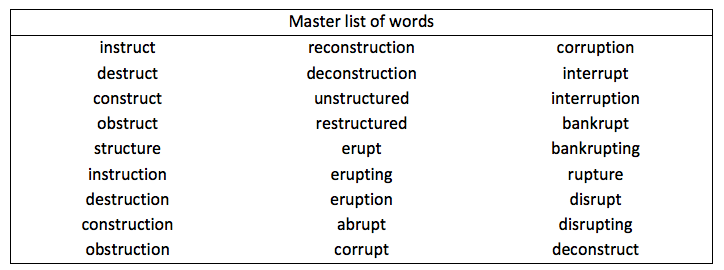

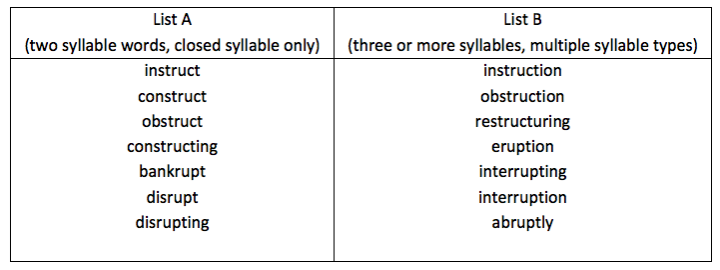

Let’s start by considering some prefixes that mean “not.” According to researchers, the prefixes im-, non-, il- and ir- appear frequently in text. So teach them, perhaps grouping them two at a time. Do the same for post, mid, inter, and fore, which are commonly occurring and united by their relationship to position. Treat Greek and Latin roots similarly. Charts are adapted from Patrick C. Manyak, James F. Baumann, Ann-Margaret Manyak, Morphological Analysis Instruction in the Elementary Grades: Which Morphemes to Teach and How to Teach Them, The Reading Teacher, 72, 3, (289–300), (2018). Differentiating Spelling instruction is stronger when it is focused. So consider teaching just three spelling patterns per week, rather than five or six. Spelling instruction is also more powerful when it supports a variety of achievement levels. So, rather than giving the same spelling list to all students, create two lists, thus providing options. A focused but rich master list, containing many words built from only a few patterns, is a good way to go. I discuss the idea of the master list in my books Super Spellers and Super Speller Starter Sets, and in previous posts on this blog. Above is a master list of words built from two Latin roots: rupt (break) and struct (build). Because these roots are commonly occurring and thematically related, teach them together. To get at the meaning of words, you’ll have to touch upon the meanings of additional prefixes and suffixes (-tion, un-, de-, in-, con-, dis-), but these won’t be the focus of your instruction. The main focus is word meaning that flows from the roots rupt and struct. Finally, differentiate your list based on the number and type of syllables in each word. Two-syllable words are less complex than three-syllable words. Likewise, words made from only one or two syllable types are less complex than words made from many syllable types. Here are two spelling lists that vary in complexity The words in your master spelling list can be used for phonics and vocabulary lessons, too. Here are some activity ideas:

Spelling deserves instructional time

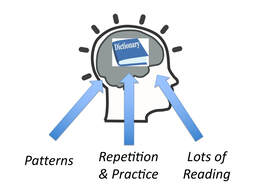

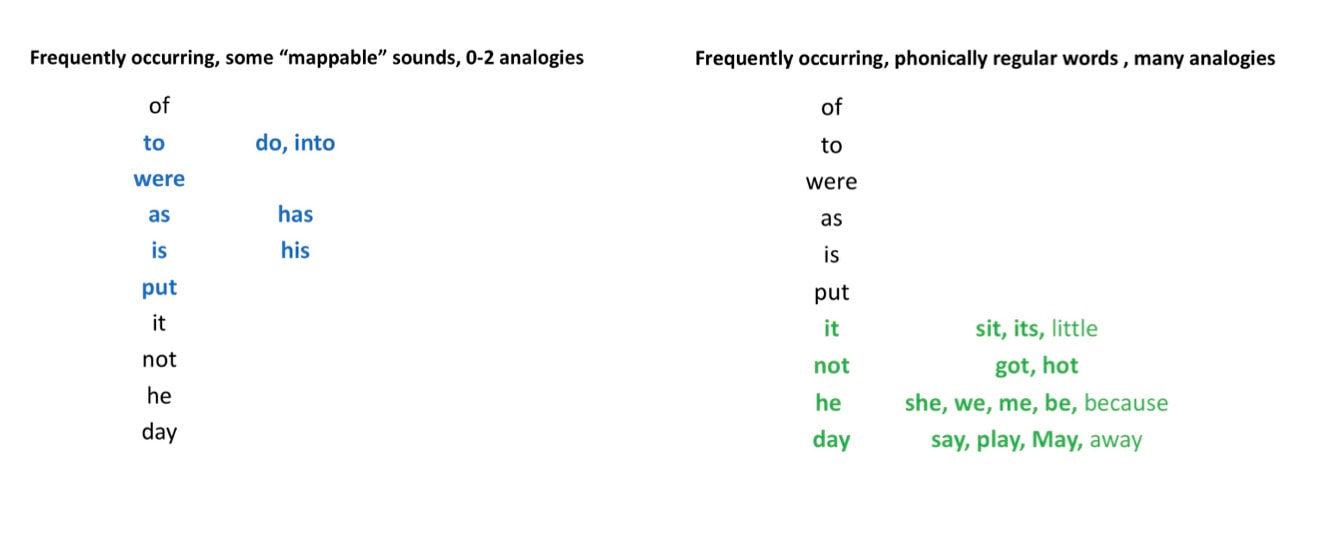

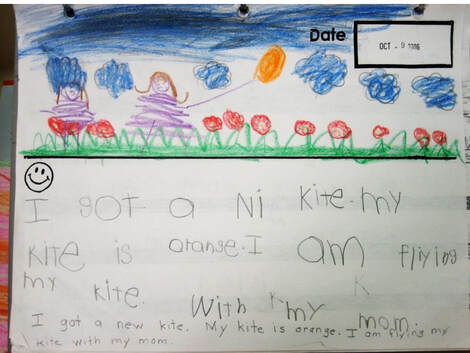

Even in middle school, students are still learning how to read. Because spelling is for reading (as well as writing), spelling is an important part of the instructional day. When you find it difficult to find enough time to teach everything, think of how spelling, vocabulary, and reading overlap. By conceptualizing spelling instruction as a way to also teach decoding and vocabulary, you can be both efficient and effective. This blog post first appeared as an article published in MiddleWeb (07/09/2019) https://www.middleweb.com/40587/spelling-matters-in-middle-school-too/ To more effectively build students' foundational reading skills, help children build a storehouse of words in their brain, and teach this basic body of store-able words in in a way that is different than traditional "sight word" instruction. Over the last three years, as I have read the research and writing of Linnea Ehri, Mark Seidenberg, and Maryanne Wolf, I often found myself reflecting upon how words are really learned and read, and how the sight word instruction I gave to my reading impaired third graders and developmentally-typical kindergarten children was, at times, inappropriate and ineffective. In March of 2018, I wrote a blog titled “No More Sight Words.” Then, just this month during a spelling presentation and in an email response to a teacher, I found myself once again discussing sight word instruction. So I thought it appropriate for me to devote this month’s blog to the body of words that many call “sight words” and a few call “early automatic reading vocabulary words” (Rawlins & Invernezzi, 2019). But my preferred term is brain words, a term coined by Richard Gentry and Gene Ouellette in their book Brain Words: How the Science of Reading Informs Teaching (Gentry & Ouellette, 2019). I prefer the term brain words because I want to move away from the term “sight words," its associated meaning, and its associated method of word instruction: presenting high-frequency and “irregular” words on cards, four to five at a time, using instruction routines that force kids to rely solely on sight to move the words into long-term memory. I’m using quotes around “sight words” and “irregular" because as we will soon see, words such as when, said, all, and some aren’t solely learned through sight, nor are they outrageously difficult to decode (and thus they are not truly irregular). The term brain words more accurately reflects how foundational reading is brought about by the workings of our brain, which encodes words in the dictionary of the mind, and best-practice instruction that presents highly-usable words in activities that connect meaning, pronunciation, and spelling. Here’s what Gentry and Ouellette have to say about words and instruction: “Teaching students to read [is] about fostering developmental changes within each student’s brain that lead to improved reading. The missing piece of effective reading instruction enables the brain to become specialized for reading so that it can store brain-based spelling representations. This process is called orthographic learning, and the resulting brain-based representations are what we call brain words” (p. 3). As I have discussed in previous posts, Mark Seidenberg’s Eternal Triangle is my go-to model for understanding the foundational workings of the reading brain. The three points of his amazing triangle are sound, spelling, and meaning (or phonology, orthography, and semantics). When we consider the triangle in light of Linnea Ehri,'s research, we know that fluent word reading occurs when children immediately pronounce and understand the words they see. These instantly recognizable words are read from memory, with no need to sound them out (Ehri, 2005, 2014). In other words, they are brain words. All words recognized automatically are brain words. A brain word is stored in the brain’s dictionary, ready for instant use in reading (or writing) whenever it is seen on a list or in a sentence. It can, of course, be found on the Dolch list and the Fry list, but it can also be found on a word wall, in a picture book, on a spelling or phonic list, and in early chapter books found in your classroom library. Linnea Ehri’s research illuminates how words are stored in the brain through repeated opportunities to engage in a process that involves decoding (turning letters into sounds) AND attaching a meaning to the combined sounds. Unfortunately, some teachers try to get children to store words in their brain dictionary through instruction that looks and sounds like this:

A week later the teacher presents five more words in the same manner. Then, a week after that, five more are given. At the end of the month, the teacher pulls the students aside, one at a time, and tests each child on the twenty words. What does she typically find? After four weeks of instruction, a few kids know most of the twenty, some know ten or twelve, some know only five, and one has failed to store any words. Presenting high-frequency words on cards to children and drilling them in a sight-based routine is something of a tradition in schools. Now, I am not necessarily knocking tradition. Traditions preserve history, foster togetherness, provide comfort, and build strength in a community or family. But some traditions hold us back and shield us from the truth. The traditional word instruction routine described above falls into the latter category. It is a practice that results in too little learning over too much time, it ignores the neuro-scientific truth of the reading process, and when students fail to master the 100, 200, or even 500 words their teachers are trying to cram into their heads, it causes worry and stress in the kids and their parents. The “learn it strictly by sight” method is problematic because it doesn’t make use of the way a human brain actually encodes written information. The human brain is a pattern recognition machine and a meaning making machine, and at its most foundational level it reads words through a seamless process of connecting sound, spelling, and meaning. This means that to efficiently and effectively teach children brain words - words that are instantly pronounced and understood when they are seen - we need instructional routines that:

For example, the word ME is best taught by teaching a child to recognize the letters M and E, associating the sounds /m/ and /e/ with the letters, building the word from letter tiles or blocks, presenting the word ME in association with other similarly patterned words (such as BE, WE, SHE, and HE, as in the "Keys of e" shown below), reading the word in books, and writing the word in sentences such as “Look at me” or “My mom wants me to go to bed.” Many, if not most, high-frequency words contain highly mappable (phonetically regular) letter-sound associations. These associations often appear in analogous words that demonstrate the same pattern. Thus, most “irregular words” aren’t very irregular! One truly irregular word is OF. It has no analogies and thus no mappable sounds. But many other words, such as put and said have highly regular consonant pronunciations -it is only the vowels that are out of the ordinary. And so, a teacher can point out that the P and T in put is the same as the P and T in pot, pit, pat, and pet, just as the S and D in said is the same as the S and D in sad, sled, and slid. And most words on the Fry and Dolch lists, such as in, that, it, just, him, ask and day, contain totally predictable patterns found in many analogous words (like spin, cat, little, must, rim, little, and say). One last thing: teachers miss the boat when they concentrate too much on brain words that convey little meaning. These are the words of Fry’s First 100 Words, words like the, was, have, are, for and from. Rawlins and Invernezzi remind us that the research of Ehri (and others) has repeatedly shown that children learn concrete nouns, adjectives, and action verbs more readily than articles and prepositions. This means it makes more sense to emphasize words such as these: food, woman, water, people, run, play, happy, and big. These are the words we want to teach to the point of becoming brain words, for once children have a repository of brain words, they are ready for guided and independent reading and writing. In their excellent Reading Teacher article Reconceptualizing Sight Words (May/June, 2019), Amanda Rawlins and Marcia Invernezzi offer five helpful assertions that speak to word learning and teaching early readers (and I would add struggling readers). They are:

In conclusion, I encourage you to talk to parents and other teachers about how children best learn words and I challenge you to swap out the term "sight word" for the term brain word. And keep your eyes on the prize: promoting lots and lots of real world language comprehension and extended reading in school and at home. As Gentry and Ouellette say in Brain Words: “The more you read and study and experience life, the more words you add to that dictionary in your brain.” (p. 4). Articles and Books Cited and Referenced

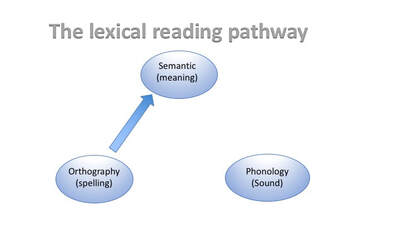

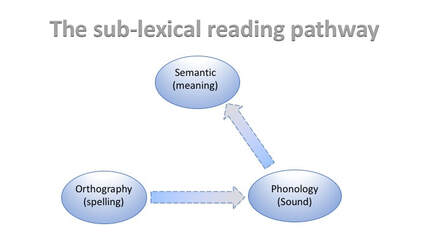

Mark Seidenberg's eternal triangle shows the fundamental elements of reading and gives a visual for the reading process. One reading pathway uses all three points of the triangle. This is the sublexical (decoding) route and it is wired through instruction that teaches young children phonemes, letter identification, sound-letter associations, and phonic/spelling patterns. Another pathway is the lexical, the reading circuit that utilizes whole words and flows between orthographic processing and semantic processing. As readers become more accomplished, this pathway is used more often because perceiving whole words and instantly connecting them to sound and meaning is more efficient than perceiving chunks, matching them to sounds, and blending everything into words. The eternal triangle also provides a way for us to understand how reading difficulties come about. When the points and pathways of the triangle are well developed and functioning smoothly, students experience fluent reading and accurate spelling. But underdeveloped and poorly performing points and pathways lead to deficits: slow and/or hesitant reading, errors while reading aloud, a lack of comprehension, a slow pace of writing, chronic spelling errors. Some reading difficulties are rooted in a lack of language comprehension. When a child lives in a language impoverished environment, she doesn’t hear and engage in word-rich conversations. This can lead to a dearth of background knowledge and vocabulary. Similarly, if her world is print impoverished, she won’t see written words, infer their meanings, or gain vocabulary through reading. Intellectual disabilities caused by birth defects or trauma can also impair language comprehension. Reading difficulties happen for other reasons. Dyslexia is a neurodevelopmental, brain-based condition that can lead to slow reading, word recognition errors, difficulty with phonemic analysis tasks, poor spelling, and slow and labored writing, among other things. Dyslexia begins with “glitches” in the genetic code. Evidence for this comes from observations of how the condition runs in families, passing from grandfather to father to son or daughter. Multiple genes are involved, but scientists don’t yet know which ones. Through the direct analysis of brain tissue, but mostly through functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), neuroscientists have gained evidence that the brain of a person with dyslexia has structure and circuitry that work differently than those of a typically achieving reader. Because phonology anchors written word learning and contributes to the act of word reading, problems with phonological processing lead to problems with word reading. It is difficult for a child with dyslexia to discriminate between sounds in a word. For example, it is hard for them to hear how words sound the same. Thus, grain and plane sound more different than alike. For kids with dyslexia, it is tough to learn the “chunks” of phonics and spelling. This, in turn, makes decoding and spelling more difficult. Impaired orthographic and phonological processing equates to poorly functioning reading pathways. Storing words in the brain dictionary is more difficult for children who have dyslexia, as is the retrieval of words that make it into storage. This leads to poor spelling as well as reading that is hesitant and error-prone. It’s like an older guitarist who can’t play a fluent solo because when he was younger, it was difficult for him to practice and play the scales. In this chart I have summarized information gleaned from Seidenberg, Shaywitz, and Wolf. It shows how the more distant causes of genetics and anomalous brain structures lead to processing problems in specific brain areas. These poorly functioning brain areas ultimately cause many of the deficit reading behaviors associated with dyslexia. THE REALITY OF DYSLEXIA “No single truth does not mean no truth.” - Iain McGilchrist We live in a time when observable facts, documented information, and scientific findings are not only questioned but are aggressively replaced by misinformation, false dichotomies, and downright lies. “Vaccines cause autism, its either jobs or the environment, climate change is a hoax and the earth is flat…” Good grief! Although debates about serious two-sided issues are healthy and necessary, and scientific truths often emerge only after decades of deliberation and argument, not all thoughts and ideas are worthy of equal consideration and, after a point, some are not worthy of consideration at all. When it comes to teaching reading, vast troves of information are available to answer questions about what constitute effective foundational literacy practices, why reading difficulties arise, and what teachers can do to prevent and correct them. Likewise, there is much evidence to support the idea that dyslexia is a biological, brain-based condition that affects how some children (and adults) think and learn, and that certain types of instruction help readers surmount difficulties caused by the condition. Dr. Sally Shaywitz said this almost fifteen years ago: “As a result of extraordinary scientific progress, reading and dyslexia are no longer a mystery; we now know what to do to ensure that each child becomes a good reader and how to help readers of all ages and all levels” (Shaywitz, 2005). Knowing the science of reading and the biological basis of some reading difficulties is tremendously important. Over the years I have talked with many parents whose children were having a hard time learning to read. These parents were distressed to see their children falling behind, upset when no one knew why their kids were struggling, and angered when they had to do battle with school systems that were unable or unwilling to assess their child fully and provide some kind of meaningful help. Unattended / unassessed dyslexia can be extremely difficult for kids, too. I have seen them frustrated, angered, and intimidated by their reading difficulties, and I’ve felt for them. If the educational community could straight up acknowledge dyslexia, it would accomplish a number of important things. First, children would be in a better position to understand themselves and not engage in blaming themselves for their difficulties. As they grow older, they could play to their strengths and work around their weaknesses. Knowing that dyslexia is a real condition helps parents, too, because they can better help their kids navigate their feelings and struggles. Finally, acknowledging dyslexia and educating others about it would help teachers understand how to instruct their students, both generally and specifically, and support children with dyslexia as they engage in the difficult task of learning to read. Acknowledging the truths of dyslexia allows us to move on to the business of “preventing and overcoming reading difficulties.” (Kilpatrick, 2015). And we need to get moving because the times in which we live demand action on many fronts. Concerning dyslexia, one action is using foundational literacy instruction that can be used to both prevent many reading difficulties and overcome them. This instruction is grounded in both science and common sense, logically arrived at, relatively easy to implement, and far removed from “pendulum swings” and “paradigm shifts.” In general, this type of instruction addresses the needs of many children, not just those with reading difficulties, takes place in general classrooms, and with some tweaking and connecting, functions in Tiers II and III as well. Also, it need not be program-based. More specifically, the instruction that prevents and overcomes reading difficulties (regardless of whether they arise from dyslexia), includes building language comprehension and background knowledge, as well as regular doses of phonemic awareness instruction (and more for those who need it), lots of phonics and spelling instruction, and many opportunities to read extended text (during all types of reading times, such as guided, independent, literature circles, and so forth). Here I want to clearly state that teaching kids phonics and teaching kids “reading” are in no way antithetical and attempts to frame reading instruction as a war between two camps is misleading and unhelpful. Teaching is inclusive, not exclusive. Thus, in all grades, kids are learning to read and reading to learn. There is decoding and encoding instruction (sometimes a lot of it) as well as metacognition and meaning instruction. And many opportunities for extended reading are present so that kids can practice their reading skills, and here I am talking about both phonics and meaning-making skills. There is too much ideological and binary thinking in our world. This is why I am dreaming of informational books devoted to literacy instruction based on multiple areas of theory and comprised of science-based, positive, and practical teaching actions that work with both whole groups and small groups, with young children and older children, and during dedicated phonics/spelling time and extended reading time. These practical actions form a foundation of basic classroom instruction as well as the bones of specialized interventions for those children who need them. In conclusion, dyslexia does exist. In the words of Dr. Timothy Shanahan, “There is a group of learners whose struggles to read are not due to any environmental problem or crummy parenting/teaching or low intelligence… These individuals, for some organic or developmental reason, can’t master reading without extraordinary effort. Whatever is disrupting the learning of these kids is within them, not around them.” The sooner we get onto the business of acknowledging truths about reading difficulties and dyslexia, and the sooner we take science-based action, the sooner we can take some weight off the shoulder of kids with dyslexia and help make their extraordinary reading efforts easier. (Thanks to Tori Bachman for inspiring this post) Citations and References

The Eternal Triangle - it sounds mysterious, like a Masonic symbol or a stone carving on an ancient Celtic tomb. Actually, the eternal triangle is a brain-based model of how we read. To understand it, let’s start with a few facts about the brain itself. Weighing only three pounds, the human brain contains approximately 85 to 95 billion branching neurons, each one firing between 5 to 50 times per second. These neurons connect and communicate with each other through more than 100 trillion synapses. Yet for all its billions of neurons, trillions of connections, and gazillions of synaptic firings, the brain requires only 20 watts of energy to run, barely enough to power small incandescent light bulb! Having evolved over millions of years, our brain is really three brains in one. First is the reptilian brain. Evolutionarily very old, reliable but rigid in its operation, and consisting of the brainstem and cerebellum, our “lizard brain” sits in back of the skull and above the spinal cord, automatically controlling vital body functions such as heart rate, breathing, and body temperature. Next is the limbic brain, which evolved in the first mammals. Its main structures are the hippocampus, amygdala, and hypothalamus. The limbic system records behavioral moments and the agreeable or disagreeable experiences associated with them. From these records, our emotions are generated. So the next time you feel angry, fearful, or joyful, thank your limbic brain. The crowning glory of the human brain is the neocortex, which first arose in the primates. Our modern-day neocortex consists of two large hemispheres, each divided into four folded lobes (frontal, temporal, parietal, and occipital) and connected by a thick band of neurons called the corpus collosum. The hemispheres of our neocortex – packed with neurons, unbelievably rich in synapses, and communicating at lightning fast speeds – give us much of what makes us human: complex language, music and song, abstract thought, imagination, and high levels of consciousness. Our hemispheres also bequeath us with the ability to read. It was eight to nine thousand years ago that humans first started using their brains to read. To turn spoken language into written text, areas of the non-reading brain were pressed into action. Parts of the visual center, typically used for facial recognition, began to process and perceive letters. Memory centers then stored these letter forms for later identification. They also stored the correct spellings of entire words, as well as their associated meanings. And sound processing centers were trained to parse speech into tiny parts called phonemes. Our brains then linked those phonemes to specific letters and letter sequences. Today, in classrooms across the country, the brains of children are shaped and trained so they can read. This teaching is necessary because unlike spoken language, reading must be taught. The teaching of reading is sometimes done by parents but mostly done by teachers. Once the basics are mastered, however, children and adults continue the teaching on their own. This is possible because the very act of reading wires each brain to read in increasingly complex and rich ways. THREE IS A MAGIC NUMBER Coined by cognitive scientist Mark Seidenberg and described in his book Language at the Speed of Sight, the eternal triangle describes the brain areas and circuitry that give rise to reading. Like all good triangles, it consists of three points and three lines. We can think of the points as areas of brain processing and the lines as the pathways (or circuitry) of language and reading. When connected, the three areas of processing that lead to reading are, in no specific order:

Here’s a brief description of each:

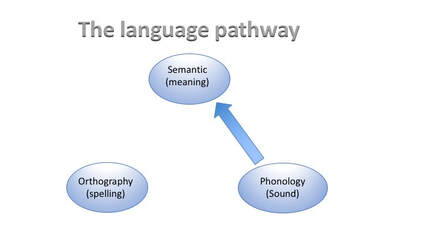

Now let’s consider the lines of the triangle, which we can think of as pathways. One line denotes the pathway of spoken language. Another is the pathway of fluent reading. A third, which is actually two lines connecting three points, describes a second reading pathway. THE LANGUAGE PATHWAY The eternal triangle shows that language is the interaction between phonological processing and semantics. Some educators add syntax to the mix. But according to Seidenberg (as well as Kilpatrick and others), research has shown that syntax has little to no effect on one’s ability to read. Thus, syntax is not included in the eternal triangle. Spoken words are stored via phonological processing. Word meanings are stored via semantic processing. The two are inextricably linked in the pathway of spoken language. As very young children, we hear words spoken by others and quickly associate their meaning, and we engage in these associations mostly on our own. As infants, we hear and observe. Soon we understand that /mama/ refers to a specific person and /dada/ refers to another. One amazing aspect of the language pathway is that it wires itself. But the wiring is sometimes given a boost by others. “Where’s your nose?” asks Grandma. A toddler touches the rubbery little lump in the middle of her face. “Good job!” grins Grandma. “Where’s your chin?” she asks next. The toddler grabs the bump below her mouth. “You’re a genius!” Grandma exclaims. As in any spoken language, English is made up words. Each word is a “blob” of sound and each blob has meaning. For example, WORM has come to mean a small, wriggling ropelike creature that lives in the ground and eats dirt. Another blob – HOP – has come to mean an action with both vertical and horizontal dimensions, is something less than a LEAP, and is probably done on one leg. Sometimes a word meaning is specific and narrow; at other times it is rich and multi-faceted. Each spoken word – NOSE, CHIN, WORM, HOP – consists of co-articulated sounds. When we are young and have not yet learned to read, or if we are living in a pre-literate society, we don’t think in terms of the individual sounds of word (phonemes). Phonemes are an artificial construct. They are, however, a construct foundational to the act of reading. And so, teaching the skills of phonemic analysis, segmentation, and manipulation is a critical part of reading instruction. This is because phonology anchors word learning and enables the act of word reading. SOUNDS TO LETTERS So far we have discussed two points of the triangle: phonology (sound) and semantics (meaning). We must add the third – orthography or spelling –for reading to occur. Orthography ultimately has to do with entire written words. But it also encompasses “chunks” or word families (both rimes, like ANK, and morphemes like DIS-), as well as single letters and letter combinations that represent single sounds. In a letter-based writing system, the individual phonemes of a language are represented by letters, which are then sequenced to create written words that can be read. We call this sound-letter association the alphabetic principle and it is a huge part of learning how to read. If children don’t master the alphabetic principle, their reading is greatly impaired or non-existent. Because encoding (spelling) is the flip side of decoding (reading), thinking of them as two sides of an inseparable whole helps us to understand how the reading process works. Once we have mastered sound-letter associations, we represent sound combinations through letter combinations. For example, we represent the spoken word /pat/ with the letter combination P-A-T. Conversely, when we read PAT, we hear /pat/ in our mind. When a young child reads various letter combinations, he works to put the sounds together into the co-articulated spoken words of language. If through spoken language the “sound blob “has been stored, and if the word has a stored meaning, then the read word (a combination of sound, meaning, and spelling) will be stored in memory. Amazingly, most children only need 4 or 5 reading repetitions to store a word in memory. Some children, however, need many more. PATHWAYS OF READING With the addition of orthography (spelling), we have the third point of our reading triangle. Now we can discuss how reading in the brain occurs along and between two basic pathways. The first reading pathway is the one that mature, competent readers use most of the time. Known as the lexical pathway (or whole word pathway), it is dependent upon only two points of the triangle: semantics and orthography. To understand how this pathway works, let’s take a minute to consider orthography. We can think of our brain’s orthographic system as a brain dictionary, a term I learned from the writings of Richard Gentry and Daniel Willingham. Stored in the brain’s dictionary are the correct letter spellings of thousands of words. We store them through a process known as orthographic mapping (more on this in another blog post) and in brain areas that were once used for non-reading purposes. Hooray for brain plasticity! To read, we visually take in letter sequences that represent sounds (words, in other words) and then we match them to meanings stored in our semantic system. The automatic action of matching a spelling sequence to a pronunciation and a meaning is known as word recognition and word recognition is the beating heart of the reading process. For word recognition to occur, all three chambers of the triangular reading heart must be beating in seamless and unending cycles of spelling-sound-meaning. Because you are a mature reader, you are using the lexical reading pathway to read most of the words in this blog. And you would certainly use it to read: The big dog ran after the ball. But even competent readers like yourself use a second reading pathway, especially when you encounter unfamiliar words in a sentence such as this: Nursultan Nazarbayev, the President of Kazakhstan, has resigned. The second reading pathway, called the sub-lexical pathway, is the sounding out or decoding pathway. Decoding can occur at the level of letters and sounds but in more advanced readers, it occurs at the “chunking” level. We break apart a word (Nur-sultan or Nur-sul-tan) to read it. And we may chunk in a few different ways (Ka-zak-hstan, Ka-zakh-stan, Kaz-akh-stan) and compare their pronunciations, all the while searching our brain’s semantic center to see if one of them matches a known word. Using context and background knowledge, we attach meaning to the decoded word. After enough practice, the word (made up of its sound, its spelling, and its meaning) becomes fully stored in our brain dictionary. Young readers rely on the sub-lexical pathway a great deal. Picture how a kindergarten reader who is just learning to “break the code” would read the sentence: Mom and Dad like the cat. At first, the sounding-out pathway is the exclusive pathway for reading. But as readers become more accomplished, they use the efficient lexical pathway more and more. The two pathways, however, are not binary (either/or). Rather, they are both/and, meaning that they function at varying levels of co-activation according to a reader’s level of reading ability, as well as a text’s level of reading difficulty (which varies according to each reader).

CONCLUSION I find the process of word reading to be fascinating. And I am in awe of the researchers who have discovered, and are continuing to discover, how the pieces of the process work together to give us the ability to effortlessly decode and deeply understand big, beautiful blocks of text. I hope you have enjoyed exercising your lexical and sub-lexical reading pathways as you’ve read this post. And I hope you find the information as interesting as I do! In June, I’ll use the language of the Eternal Triangle to describe the reading difficulties many children experience. I’ll also talk about dyslexia and how the eternal triangle informs our understanding of that condition. Until then, I wish you the best with you're the end of the school year. Happy almost-summer! |

Mark WeaklandI am a teacher, literacy consultant, author, musician, nature lover, and life long learner.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed