|

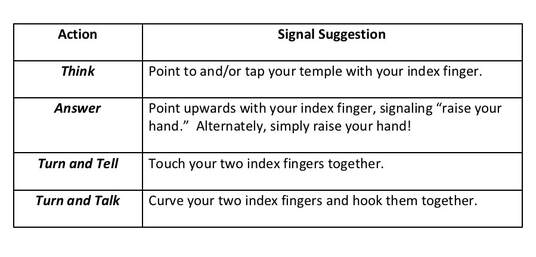

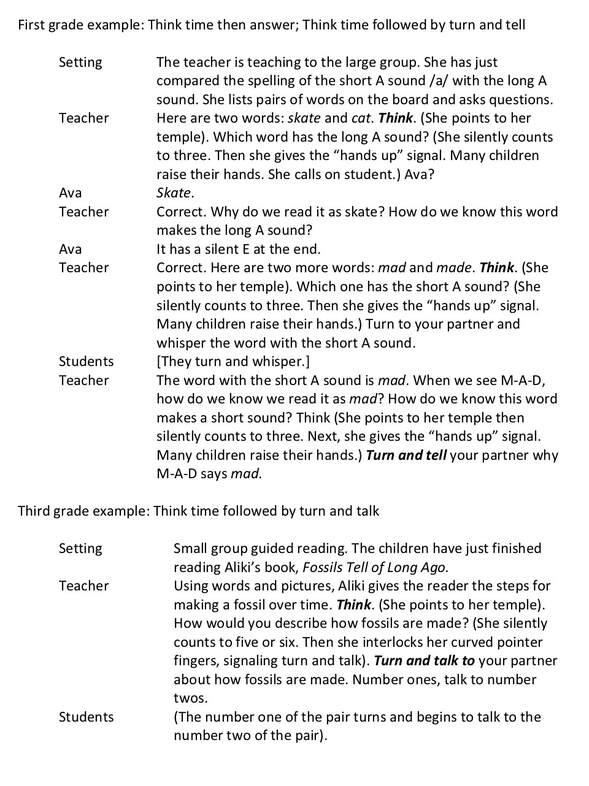

Teaching is hard work. So, it makes sense that you carefully consider how you spend your instructional energy each and every day. You want to maximize your efforts, minimize wasted time, and ultimately enjoy the fruits of your labors. What general instructional practices help you do this? Five immediately come to mind: 1) think time, 2) direct and explicit instruction, 3) descriptive reinforcement, 4) repetition, and 5) instant error correction. These five have a terrific research track record, lead to great gains in learning (when effectively employed), work with all children, are especially helpful to those who struggle to learn, and can be used to teach all subjects, including reading, writing, and spelling. Think Time Today’s post concentrates on think time, an instructional technique that promotes comprehension and language use. At its core, think time involves 1) a teacher asking a question or requesting an action, and 2) students thinking silently for three to five seconds before raising their hands to answer or turning to talk to a partner to discuss. Consistently fold think time into your instruction and I guarantee you’ll be amazed at how student answers become richer and more sophisticated, and children become more engaged. During instruction that does NOT provide think time, a teacher might ask her kindergarten students (after reading the book Swimmy by Leo Leonni), “Who is the main character?” Immediately, two, three, or four hands might shoot up. The teacher quickly calls on one of the hand-raisers, listens for the correct answer, and then moves on. With think time, you ask students the same question. But then you require them to think a little before raising their hands. Your requiring looks like silently counting: 1, 2, 3. As you count, the children think quietly and you scan the group, checking to see that everyone is thinking. Next you give a signal that it’s time to raise their hands. This time, twelve or more hands whoosh into the air. Finally, you call on a student, or even better, you give a signal to the children that tells them to turn and tell a partner the answer. As the children whisper their responses, you listen. Three seconds of think time is suggested for kindergarten children because their attention span is very short (roughly that of a gnat or hamster). If you provide too much time, you’ll lose them. For first and second graders, keep think time at three seconds, or increase it to four or five. For older students, give up to seven or eight seconds. Decide what amount of time works best for your students. The general behavior of different groups may demand more or less time. Also, vary the amount of time depending upon the task. Students benefit from four or five seconds, or maybe a bit more, if the question demands a longer, more complex answer. You should expect your students to accurately engage in thinking during your lessons. Many teachers model active listening. Do the same for active thinking. First, you may want to model what non-thinking looks like (gazing around the room, fidgeting, playing with an eraser, poking someone nearby, … the list is endless). Then, model what thinking looks like (furrowed brow, squinty eyes, general looks of concentration and pondering). You can also do a think aloud, saying something like, “I was just asked to name a color I see in the classroom. I looked around and saw yellow, blue, and red. Now I am thinking that I will pick blue. Blue is my answer.” Take the technique to its next step by modeling what “turn and tell” looks like (a short burst of quiet talking in which one student turns to another and tells her partner an answer). Also model “turn and talk” (a longer period of quiet talking in which two students share their thoughts related to a question or direction given by the teacher). One suggestion is that you identify classroom activities that benefit most from think time. I like to use it in almost every questioning situation. But open-ended questions, or a question that begin with “why,” are especially appropriate times to use think time. Another suggestion is to use hand signals for “think,” “answer,” “turn and tell,” and “turn and talk.” This keeps students focused on you, as well as insures that your instruction isn’t broken up with too much teacher talk. Here are some signal suggestions. But if you have your own clever alternatives, please, be my guest! Here are two more examples of think time in action. Although the examples are labeled first and third, it’s best if you think in terms of a grade band. Depending upon the needs, behaviors, and achievement levels of the majority of students in any classroom, any one of the scenes in this section could play out in any grade level. The Real Reason to Use It

Often called wait time in research literature, think time gives your students time to think more broadly and deeply about the questions you are asking them, as well as to mentally rehearse an appropriate response. In turn, this thinking and rehearsing enables kids to speak more fluently while answering, give longer answers, and use more sophisticated and appropriate vocabulary words. Additionally, during any instruction, be it large group or small, social studies or math, think time engages more students, many more than during a call-and-response questioning. By call-and-response, I mean this: the teacher asks a question, a few kids raise their hands, the teacher calls on one student, that student answers while the others sit mutely or stare into space, and then the teacher repeats the sequence with another question. Think time is more effective than call-and-response because when you scan the room as you silently wait for students to think, you send the message that engaged thinking is expected. And if you couple think time with “turn and tell” or “turn and talk” (a.k.a. discuss), you crank up the engagement level even more. Another benefit of think time is that it allows for what I call “self-differentiation.” For example, when a teacher asks her class to recall the events in a story, children who are less advanced at thinking and remembering can focus on the lastevent of the story, while more advanced students can recall the middle or beginning events, too. If you call on the less advanced student first, you build in an opportunity for that child to 1) share, and 2) be successful. After that student’s response, call on a child who is more likely to remember a middle or beginning event. Viola! When you insert a three to five second space for thinking into your questioning, you allow your students to think at the level most natural for them. This increases the engagement of all your learners and provides more opportunities for every student to experience success. This is also why think time is a must when working with children in special education classrooms or inclusionary settings. Research on the effectiveness of wait time began in the 1970s, hit its stride in 80s, and still regularly appears in journals. More than 40 years ago, Mary Rowe may have been the first to coin the term wait time and describe its importance to the overall quality of student responses (and thus of learning). Later, Robert Stahl expanded on Rowe’s concept and recommended three second “waits” at various points during class periods. The research of Rowe, Stahl, and others shows that wait time is a powerful way to increase the length and quality of student responses, as well as boost student motivation. More recently, studies done by Barbara Wasik, Annemarie Hindman, and others have examined the effectiveness of wait time with students in first and second grade, kindergarten, and even preschool.

|

Mark WeaklandI am a teacher, literacy consultant, author, musician, nature lover, and life long learner.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed