|

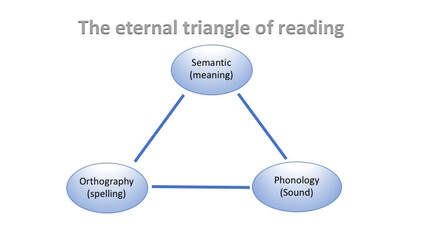

The Eternal Triangle - it sounds mysterious, like a Masonic symbol or a stone carving on an ancient Celtic tomb. Actually, the eternal triangle is a brain-based model of how we read. To understand it, let’s start with a few facts about the brain itself. Weighing only three pounds, the human brain contains approximately 85 to 95 billion branching neurons, each one firing between 5 to 50 times per second. These neurons connect and communicate with each other through more than 100 trillion synapses. Yet for all its billions of neurons, trillions of connections, and gazillions of synaptic firings, the brain requires only 20 watts of energy to run, barely enough to power small incandescent light bulb! Having evolved over millions of years, our brain is really three brains in one. First is the reptilian brain. Evolutionarily very old, reliable but rigid in its operation, and consisting of the brainstem and cerebellum, our “lizard brain” sits in back of the skull and above the spinal cord, automatically controlling vital body functions such as heart rate, breathing, and body temperature. Next is the limbic brain, which evolved in the first mammals. Its main structures are the hippocampus, amygdala, and hypothalamus. The limbic system records behavioral moments and the agreeable or disagreeable experiences associated with them. From these records, our emotions are generated. So the next time you feel angry, fearful, or joyful, thank your limbic brain. The crowning glory of the human brain is the neocortex, which first arose in the primates. Our modern-day neocortex consists of two large hemispheres, each divided into four folded lobes (frontal, temporal, parietal, and occipital) and connected by a thick band of neurons called the corpus collosum. The hemispheres of our neocortex – packed with neurons, unbelievably rich in synapses, and communicating at lightning fast speeds – give us much of what makes us human: complex language, music and song, abstract thought, imagination, and high levels of consciousness. Our hemispheres also bequeath us with the ability to read. It was eight to nine thousand years ago that humans first started using their brains to read. To turn spoken language into written text, areas of the non-reading brain were pressed into action. Parts of the visual center, typically used for facial recognition, began to process and perceive letters. Memory centers then stored these letter forms for later identification. They also stored the correct spellings of entire words, as well as their associated meanings. And sound processing centers were trained to parse speech into tiny parts called phonemes. Our brains then linked those phonemes to specific letters and letter sequences. Today, in classrooms across the country, the brains of children are shaped and trained so they can read. This teaching is necessary because unlike spoken language, reading must be taught. The teaching of reading is sometimes done by parents but mostly done by teachers. Once the basics are mastered, however, children and adults continue the teaching on their own. This is possible because the very act of reading wires each brain to read in increasingly complex and rich ways. THREE IS A MAGIC NUMBER Coined by cognitive scientist Mark Seidenberg and described in his book Language at the Speed of Sight, the eternal triangle describes the brain areas and circuitry that give rise to reading. Like all good triangles, it consists of three points and three lines. We can think of the points as areas of brain processing and the lines as the pathways (or circuitry) of language and reading. When connected, the three areas of processing that lead to reading are, in no specific order:

Here’s a brief description of each:

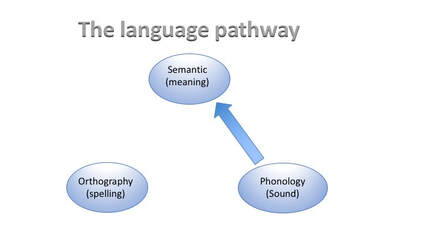

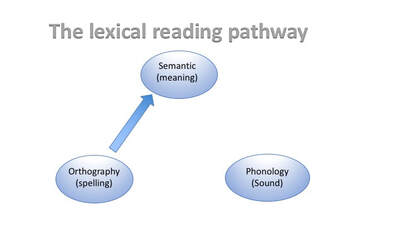

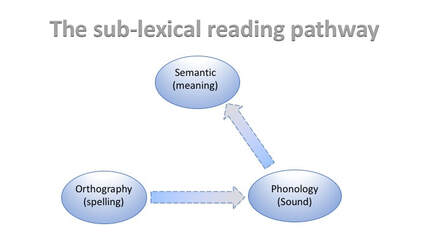

Now let’s consider the lines of the triangle, which we can think of as pathways. One line denotes the pathway of spoken language. Another is the pathway of fluent reading. A third, which is actually two lines connecting three points, describes a second reading pathway. THE LANGUAGE PATHWAY The eternal triangle shows that language is the interaction between phonological processing and semantics. Some educators add syntax to the mix. But according to Seidenberg (as well as Kilpatrick and others), research has shown that syntax has little to no effect on one’s ability to read. Thus, syntax is not included in the eternal triangle. Spoken words are stored via phonological processing. Word meanings are stored via semantic processing. The two are inextricably linked in the pathway of spoken language. As very young children, we hear words spoken by others and quickly associate their meaning, and we engage in these associations mostly on our own. As infants, we hear and observe. Soon we understand that /mama/ refers to a specific person and /dada/ refers to another. One amazing aspect of the language pathway is that it wires itself. But the wiring is sometimes given a boost by others. “Where’s your nose?” asks Grandma. A toddler touches the rubbery little lump in the middle of her face. “Good job!” grins Grandma. “Where’s your chin?” she asks next. The toddler grabs the bump below her mouth. “You’re a genius!” Grandma exclaims. As in any spoken language, English is made up words. Each word is a “blob” of sound and each blob has meaning. For example, WORM has come to mean a small, wriggling ropelike creature that lives in the ground and eats dirt. Another blob – HOP – has come to mean an action with both vertical and horizontal dimensions, is something less than a LEAP, and is probably done on one leg. Sometimes a word meaning is specific and narrow; at other times it is rich and multi-faceted. Each spoken word – NOSE, CHIN, WORM, HOP – consists of co-articulated sounds. When we are young and have not yet learned to read, or if we are living in a pre-literate society, we don’t think in terms of the individual sounds of word (phonemes). Phonemes are an artificial construct. They are, however, a construct foundational to the act of reading. And so, teaching the skills of phonemic analysis, segmentation, and manipulation is a critical part of reading instruction. This is because phonology anchors word learning and enables the act of word reading. SOUNDS TO LETTERS So far we have discussed two points of the triangle: phonology (sound) and semantics (meaning). We must add the third – orthography or spelling –for reading to occur. Orthography ultimately has to do with entire written words. But it also encompasses “chunks” or word families (both rimes, like ANK, and morphemes like DIS-), as well as single letters and letter combinations that represent single sounds. In a letter-based writing system, the individual phonemes of a language are represented by letters, which are then sequenced to create written words that can be read. We call this sound-letter association the alphabetic principle and it is a huge part of learning how to read. If children don’t master the alphabetic principle, their reading is greatly impaired or non-existent. Because encoding (spelling) is the flip side of decoding (reading), thinking of them as two sides of an inseparable whole helps us to understand how the reading process works. Once we have mastered sound-letter associations, we represent sound combinations through letter combinations. For example, we represent the spoken word /pat/ with the letter combination P-A-T. Conversely, when we read PAT, we hear /pat/ in our mind. When a young child reads various letter combinations, he works to put the sounds together into the co-articulated spoken words of language. If through spoken language the “sound blob “has been stored, and if the word has a stored meaning, then the read word (a combination of sound, meaning, and spelling) will be stored in memory. Amazingly, most children only need 4 or 5 reading repetitions to store a word in memory. Some children, however, need many more. PATHWAYS OF READING With the addition of orthography (spelling), we have the third point of our reading triangle. Now we can discuss how reading in the brain occurs along and between two basic pathways. The first reading pathway is the one that mature, competent readers use most of the time. Known as the lexical pathway (or whole word pathway), it is dependent upon only two points of the triangle: semantics and orthography. To understand how this pathway works, let’s take a minute to consider orthography. We can think of our brain’s orthographic system as a brain dictionary, a term I learned from the writings of Richard Gentry and Daniel Willingham. Stored in the brain’s dictionary are the correct letter spellings of thousands of words. We store them through a process known as orthographic mapping (more on this in another blog post) and in brain areas that were once used for non-reading purposes. Hooray for brain plasticity! To read, we visually take in letter sequences that represent sounds (words, in other words) and then we match them to meanings stored in our semantic system. The automatic action of matching a spelling sequence to a pronunciation and a meaning is known as word recognition and word recognition is the beating heart of the reading process. For word recognition to occur, all three chambers of the triangular reading heart must be beating in seamless and unending cycles of spelling-sound-meaning. Because you are a mature reader, you are using the lexical reading pathway to read most of the words in this blog. And you would certainly use it to read: The big dog ran after the ball. But even competent readers like yourself use a second reading pathway, especially when you encounter unfamiliar words in a sentence such as this: Nursultan Nazarbayev, the President of Kazakhstan, has resigned. The second reading pathway, called the sub-lexical pathway, is the sounding out or decoding pathway. Decoding can occur at the level of letters and sounds but in more advanced readers, it occurs at the “chunking” level. We break apart a word (Nur-sultan or Nur-sul-tan) to read it. And we may chunk in a few different ways (Ka-zak-hstan, Ka-zakh-stan, Kaz-akh-stan) and compare their pronunciations, all the while searching our brain’s semantic center to see if one of them matches a known word. Using context and background knowledge, we attach meaning to the decoded word. After enough practice, the word (made up of its sound, its spelling, and its meaning) becomes fully stored in our brain dictionary. Young readers rely on the sub-lexical pathway a great deal. Picture how a kindergarten reader who is just learning to “break the code” would read the sentence: Mom and Dad like the cat. At first, the sounding-out pathway is the exclusive pathway for reading. But as readers become more accomplished, they use the efficient lexical pathway more and more. The two pathways, however, are not binary (either/or). Rather, they are both/and, meaning that they function at varying levels of co-activation according to a reader’s level of reading ability, as well as a text’s level of reading difficulty (which varies according to each reader).

CONCLUSION I find the process of word reading to be fascinating. And I am in awe of the researchers who have discovered, and are continuing to discover, how the pieces of the process work together to give us the ability to effortlessly decode and deeply understand big, beautiful blocks of text. I hope you have enjoyed exercising your lexical and sub-lexical reading pathways as you’ve read this post. And I hope you find the information as interesting as I do! In June, I’ll use the language of the Eternal Triangle to describe the reading difficulties many children experience. I’ll also talk about dyslexia and how the eternal triangle informs our understanding of that condition. Until then, I wish you the best with you're the end of the school year. Happy almost-summer! |

Mark WeaklandI am a teacher, literacy consultant, author, musician, nature lover, and life long learner.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed