|

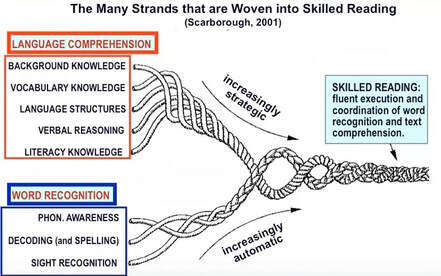

For more than thirty years, neuroscientists and reading researchers have been collaborating to discover how reading “happens” at the level of brain structures, neural circuitry, and even the neuron itself. It’s exciting to know that their hard work is paying off. Now, many parts of the “reading brain” have been identified and the reading process is generally understood, including how letters and sounds are visually and aurally processed, how letters and sounds are associated and turned into words, how word spellings are stored in brain areas, and how decoding, word spellings, and language comprehension (or meaning) come together and give rise to the act of reading. Last but not least, instructional practices have been created from this knowledge. These practices activate and strengthen the brain areas and circuits involved in reading and writing. In many classrooms, teachers are using these practices to teach reading and to help struggling readers become successful and confident readers. If the word keeps getting out about the science of reading and its related instructional practices, a preponderance of schools will make use of these practices and this, in turn, will increase reading achievement, especially for those children who struggle. Who will get the word out on the reading brain and the instruction that strengthens it? In the book Theoretical Models and Processes of Reading(ILA, 2013), George Hruby and Usha Goswami present a chapter titled Educational Neuroscience for Reading Researchers(p. 558-588). Early in the chapter, one sentence caught my eye: “… the field [of neuroscience] has a clear need for literacy education scholars who are knowledgeable about the developmental and life sciences – individuals who could make use of insights from the disciplines such as neuroscience to help inform reading theory, policy, and research.” The sentence spoke to me for two reasons: 1) it neglected to specifically mention classroom instruction as an area in need of informing, and 2) I believe that literacy education scholars, ones who might make use of neuroscience insights, are on the scene now and are actively engaged in the process of “informing reading theory, policy, and research.” In addition, these scholars are taking their insights to the next level by explaining how the science of reading can be turned into classroom reading instruction beneficial to all learners and critical to struggling readers. There are many of these literacy education scholars. Five of them have special importance to me. Because they wear many hats (author, researcher, scientist, presenter), the five are able to synthesize information to explain the workings of the reading brain, as well as offer effective classroom instructional practices (based on science) that help teachers alleviate and possibly eradicate reading impairments. Here are my top five literacy education scholars, along with their must-read books: Maryann Wolf: Proust and the Squid (2008) Mark Seidenberg: Language at the Speed of Sight (2015) Sally Shaywitz: Overcoming Dyslexia (2008) David Kilpatrick: Essentials of Assessing, Preventing, and Overcoming Reading Difficulties (2015) Richard Gentry & Gene Ouellette: Brain Words (2019) To be clear, these science-minded writers are the ones who have helped me deeply understand how reading “works” at its most fundamental levels. You might have your own gurus (Daniel Willingham immediately comes to mind). And of course both the writing and the research of these five is based on a body of work – broad and deep and more than thirty years in the making – that was built by dozens of brilliant researchers, including Linnea Ehri, Marilyn Adams, Nicole Speer, Bruce McCandliss, Allan Paivio, and many others. My journey of understanding brain-based reading began with a two-year exploration of spelling and some direct and explicit instruction from Dr. Richard Gentry, who told me why spelling is for reading. Thanks, Dr. Gentry! It grew as I explored the work of Allan Paivio (the dual coding model of reading) and Linnea Ehri (the phases of word learning). Next, I synthesized that information with what I learned from Mark Seidenberg’s reading framework, which he calls the Eternal Triangle. Most recently, I’ve connected all of this to the Simple View of Reading, a brilliant and elegant formulation of what reading is (at a fundamental level). I know many teachers have been aware of the Simple View's formula (Reading comprehension = word level reading x language comprehension) for many years now. I was late to the table, but better to feast later than never, right? I do remember the "Rope of Reading" that was popular in the early 2000s, but some reason I never connected it to the framework that is the Simple View of Reading. Perhaps you have your favorite group of research-writers who have informed your practices. If you are reading this blog, I bet you do! As for me, I’ll continue my exploration with more reading and teaching, as well as more commentary (in upcoming blog posts) on the Simple View of Reading and the Eternal Triangle. In these posts, I’ll make connections from the two frameworks to the condition of dyslexia, as well as to engaging and effective classroom instructional practices that, in the words of literacy guru David Kilpatrick, “prevent and overcome reading difficulties.” |

Mark WeaklandI am a teacher, literacy consultant, author, musician, nature lover, and life long learner.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed