|

We are now at least seven weeks into the new school year. Yikes! Where does the time go? The days are getting short but there’s still time for some last minute gardening, a bike ride, or stroll down the lane or around the block. During my strolls, my mind often meanders into areas of education: how to help principals efficiently create new literacy programs, how to help kids enjoy writing more, how to help teachers teach children to read and write. In a session yesterday at the amazing 2017 KSRA Conference (happy 50th year, KSRA!), I talked with teachers about spelling instruction. Because spelling is an overlooked way to boost reading achievement, my goal was to convince teachers that they should spend time on quality spelling instruction, as well equate quality spelling time to quality “becoming a better reader” time. To that end, I offer a few thoughts on how spelling ability does and does not develop.

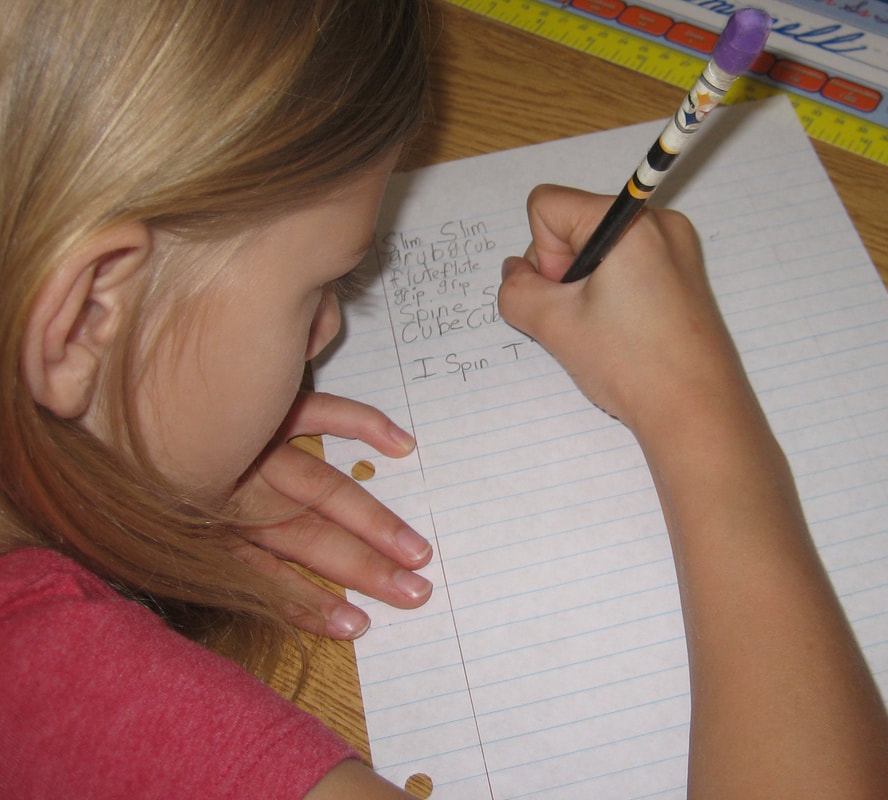

Spelling ability doesn’t develop from memorizing a weekly word list. The most effective spelling instruction is not a weekly routine in which you give your students a list of words, have them complete worksheets and write the words numerous times at home, give them an end of the week test where they regurgitate the words from memory, and then move on to another list of words. This “memorize-and-move-on” routine does little to help children become better spellers, readers, and writers. In my opinion, children who become accomplished spellers in classrooms that use a “memorize-and-move-on” program learn to spell in spite of the program. This is not to say that memory does not play a part in spelling. It does. A well-developed lexicon or “dictionary” of words in the brain is a construct that is critical to fluent reading. This dictionary can be built through well-designed practices, including word study, strategy use, and a great deal of practice in reading, writing, and spelling. In the end, letter-sound relationships, spelling patterns, and eventually, entire words are committed to memory. Spelling instruction that is mastery based, strategy based, differentiated, and centered on sound, pattern and meaning is something very different from instruction that consists of little more than introducing and then testing on a memorize-and-move-on weekly spelling list. Spelling words taught via effective instruction, a focused word list, and a repeating cycle of test-study-test are much more likely to become permanent in a student’s mind. Our ability to spell is improved when we can remember the “look” of a word. Typically, this type of memorizing occurs when we see a word (and related words) many times through repeated exposure. Practice makes permanent, and specific types of instruction and word activities lend themselves to this achievement of permanency. A weekly routine of “memorize-and-move-on” does not. Spelling does develop from excellent instruction If spelling ability doesn’t develop from memorizing a weekly word list, then how does it develop? Additionally, how do we know that there is more to spelling than memorizing and recalling letter sequences? And what should spelling instruction consist of if we need to teach more than how to memorize a weekly word list, week after week after week? One piece of evidence about how to develop spelling ability comes from research that has shown that it is easier for children to remember predictable words than it is for them to remember irregular words (Treiman 1993). Think about it. If spelling were simply an act of memorizing, it should be just as easy for kids to memorize the spelling of irregular words, such as want, does, and said, as it is for them to spell more predictable words like list, slap, and joke. After all, every one of them is al four-letter word. But we know from experience that the first set of words (want, does, and said) is more problematic for children to spell. Some four-letter words are easier to spell than others! If your teaching career has been anything like mine, then you have seen more than your fair share of wunt, duz, and sed. If memorizing a letter sequence were all there was to it, then it should be just as easy for me to spell silhouette and ricocheted as it is for me to spell cannonball and instruction (all ten-letter words). In the interest of full disclosure, it took me three tries with my spell-checking program to spell ricocheted. Cannonball and instruction were not a problem. Spelling is difficult for me, so if I am really interested in learning how to spell silhouette accurately every time I write it, I should learn a strategy for remembering it and then practice employing that strategy as I spell the word multiple times. Research has also shown that children have a limited visual memory for letter sequence. I was surprised to learn that when spelling, a child holds only two to three letters in sequence (Aaron, Wilcznski, and Keetay 1998). Thus, visual memory does not account for how our students spell four- and five-letter words, let alone multisyllabic words. Because children don’t typically spell by visually recalling a string of letters, memorizing a standardized weekly word list does little to help children learn how to spell. So what does? What type of instruction helps kids learn how to spell? At the most basic level, spelling ability develops from excellent instruction. More specifically, the most effective spelling instruction is: • systematic and sequential; • direct and explicit (at times); • focused and mastery based; • differentiated; • strategy based; and • centered on sound, pattern, and meaning. In my next blog, I'll write more about what each of these bullet statements means and looks like in the classroom. |

Mark WeaklandI am a teacher, literacy consultant, author, musician, nature lover, and life long learner.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed