|

Here is a fact: Journalist Emily Hanford helped popularize the term “Science of Reading,” Some would call that fact a dead fact. Here’s another fact: It takes some children hundreds of repetitions to associate a sound with a letter. I call that fact a live fact. Okay, here’s another dead fact: The term dyslexia is made from two Greek roots, dys, meaning “difficult or inadequate,” and lexis, meaning “word.” Now, another live fact: Teaching students the six syllable types can increase their chance of mastering encoding and decoding. Are you starting to see how dead and live facts differ? What is a dead fact? In his thought-provoking book If Nietzsche Were a Narwhal: What Animal Intelligence Reveals About Human Stupidity, author Justin Gregg explores how unique human cognitive abilities, such as mental time travel and creating moral systems, are double-edged swords, each as likely to lead to individual suffering and world catastrophe as to personal contentment and a livable future. In one chapter, Gregg introduces the term dead facts. Coined by philosopher Ruth Garrett Millikan, dead facts have to do with the human brain’s tendency to elaborate and expound upon (to think thoughts about) incoming sensory information. To understand just what a dead fact is, let’s first consider a nonhuman brain and its reaction to sensory input. For example, if I were a rabbit and I heard a loud rustling behind a nearby tree, I would bolt in the opposite direction. Why? As a rabbit I know this fact: rustling equals danger. And so I run! Most animals that hear rustling probably don’t think anything more than rustling equals danger. Humans, however, are different. My human brain might quickly move from “rustling equals danger” to thoughts about why the rustling is happening. It's a fox, I think, or a falling branch. Or maybe it's a coyote. Could it be a wolf? Just as quickly, my brain might fabricate more improbable thoughts. For example, I might remember the time I played hide and seek with my sister, who was hiding behind a tree. Then I might think, “Wouldn’t it be crazy if my sister is making that rustling sound?” Cooler still, I might wonder “What if the rustling is caused by a lost extraterrestrial or a sasquatch, hiding to avoid detection?” For humans, these recollections and imaginings are simply how we roll – one event occurring in our environment can trigger the remembering of countless bits of trivia and the dreaming of endless stories of fiction. Ruth Millikan called these kinds of thoughts dead facts because they have nothing to do with our acting on incoming sensory data in ways that boost our chances of immediate survival. This is not to say that our wishful thinking and imaginative musings don’t have a place in the world. I enjoy thinking weird and whimsical thoughts. And ever-evolving thoughts and connections often lead to innovations, solutions, art, and religions. But when it comes to the efficient solving of an immediate problem, fabrications, ruminations, and the random recall of trivia can distract us. Which leads me to reading instruction. Live Facts for Reading Instruction

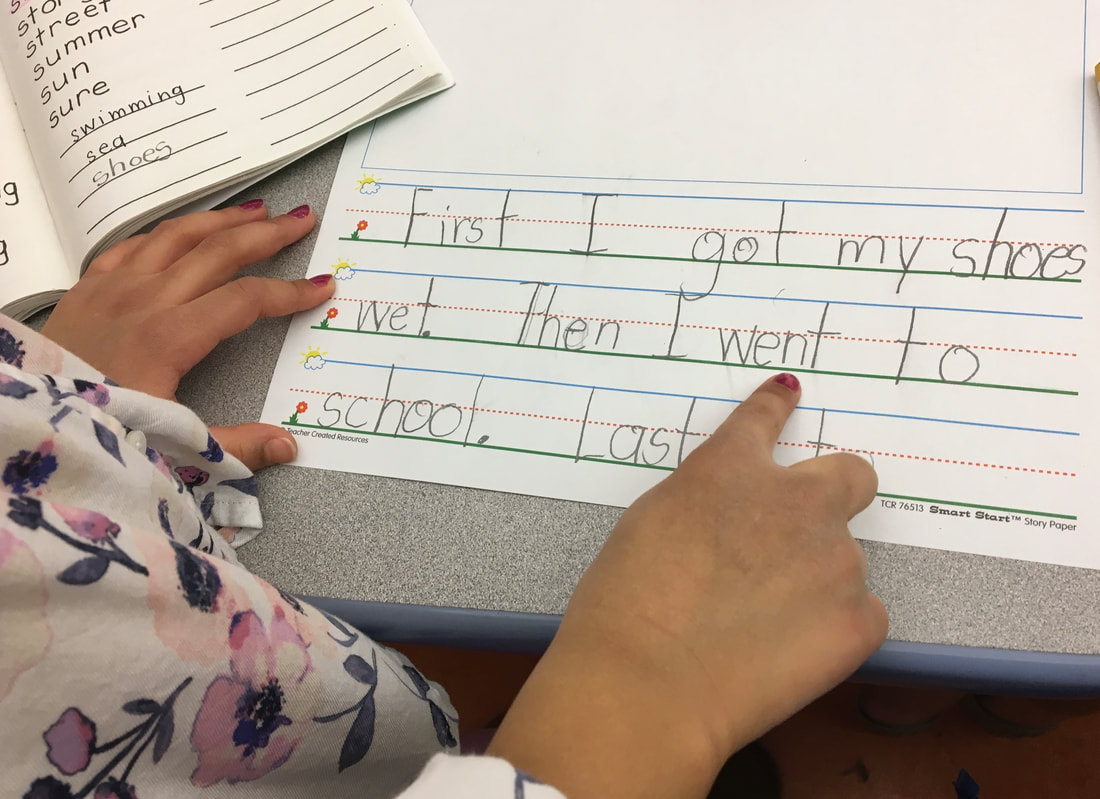

Yes, facts like “journalist Emily Hanford helped popularize the term science of reading” and “the term dyslexia is made up of two Greek roots” are fun to know. But they are of no use to me when comes time to teach kindergarten students sound-letter associations or help a dyslexic adult become a more fluent reader. Thus, I want to stay focused on live facts, the ones most useful in my day-to-day instruction and capable of lifting my teaching to the most effective level. Here are some live facts I strive to keep in mind:

In conclusion, when it comes to reading instruction, consider the facts and decide which ones are dead and which ones are live. Then give the live facts priority! Review them on a regular basis and keep them in a brain space that is easily accessible. Finally, use them as the foundation of your reading, writing, and spelling instruction. When instruction is built upon a firm foundation of live facts - facts that enable efficient and effective teaching - students more easily become thriving readers, writers, and spellers. |

Mark WeaklandI am a teacher, literacy consultant, author, musician, nature lover, and life long learner.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed