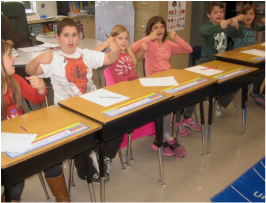

Previously I discussed the general idea of why we should teach spelling, not merely give assignments. Now I’d like to talk specifics: first, why it’s a good idea to teach spelling strategies, and then a specific strategy that teachers can teach younger students. (Early next month I’ll present one for older students.) Just as it is useful to have strategies while driving - setting the cruise control to avoid inadvertently speeding on the highway, regularly checking mirrors in heavy traffic– it is useful for students to have strategies they can employ while reading, writing, and spelling. Whether it’s adjusting their reading rate, reading their writing out loud to check for errors, or spelling unknown words by assigning letters to sounds, all children make use of literacy strategies. To get kids to the point where they use strategies automatically, we must first have them practice strategies intentionally. Thus, we must explicitly teach strategies to our students, model strategies for them, guide them as they use strategies, and finally step back and let them independently use what they’ve learned. But before we teach strategies, we need to raise our students’ awareness of this fact: when they spell, especially during writing, they will surely misspell some words, even if they are accomplished spellers. Thus, we should tell our students “even good spellers make mistakes.” Equally important, students need to hear from us that “good spellers work to fix their mistakes.” We want our students to know that when they don’t know how to spell a word, they can purposefully use a spelling strategy to get close to the correct spelling and, later, to spell the word exactly. Here is one spelling strategy children can use. Consisting of three parts, it’s a strategy for any child, younger or older, who is in the early stages of spelling development. Hear and Spell the Sounds In the earliest stages of spelling, spellers hear a word aloud or in their heads (audiation) and then translate or encode the sounds into letters. When it comes to helping students notice the sounds in words (in order to assign letters to them), I’d say stretching the word, zapping the sounds, and feeling the chin drop are three easy and effective strategies to teach. Stretching and zapping are best for single-syllable words. The chin drop is best for children encountering multi-syllable words, such as fantastic and locomotion. Stretching, zapping, and feeling your chin drop develop phonemic awareness, which is beneficial for students in the early stages of spelling development, as well as for those behind in reading, writing, and spelling. Reporting on its meta-analysis of research studies, the National Reading Panel clearly stated that teaching phonemic awareness not only helps preschoolers, kindergartners, and 1st graders learn to read, but also older readers with reading problems. (NICHD, 2000). These three concrete actions (stretch, zap, drop your chin) function as stepping stones to the sound-letter stage of spelling development. When children do them they can better understand the abstract concept that words are made up of sounds. Early in the school year, a kindergarten child might segment the word lap into its component sounds - /l/, /a/, /p/- and stop there. But later that child must spell the word by assigning correct letters to each sound. For young readers, the process is reversed: letters are seen, sounds are assigned to the letters, and the sounds of the letters come together to make words. At first, encoding and decoding a word may involve a series of matching one letter to one sound. The words bat, flip, and slaps lend themselves to this one-to-one sound and letter matching. Later, word chunks are recognized, such as the ch and ur chunks in the word church or the th and ank chunks in the word thank. At this point spellers are entering the pattern recognition stage of spelling development. Still later, words are recognized in their entirety. Speaking from personal experience, explicit phonemic awareness instruction not only works wonders for kindergartner children, it also benefits struggling third graders. I've even done phonemic awareness activities with fifth grade students in special education. Stretch the Word In my last years in public education, I worked with an especially talented group of kindergarten teachers (yes, I'm talking about you, United Elementary School K teachers). All of them taught two specific techniques that helped their students hear the sounds in words. One technique was stretching and the other was zapping. To stretch a word, tell your students to imagine the word as a big, strong rubber band. Grab hold of either end of the word (make two fists and hold them in front of you) and then slowly pull your hands away from each other, stretching the word out, holding out the vocalization of each phoneme as you stretch. Keep in mind some consonants can be held and stretched (m, f, l, s, z), while other cannot (b, t, k, p). Here are some 2nd graders stretching out the sounds of a word prior to spelling it. Some teachers teach this technique as “bubble gum words.” Students grab hold of the word with their thumb and index finger then stretch the sounds out in front of them, like they are pulling and stretching a wad of bubble gum. Regardless of whether the word is a rubber band or a wad of gum, it’s best to start with words that have consonants and vowels that can be “held,” such as f, l, m, s, short a and short o. Don’t start with words such as bait or coin. Instead, start with words like sat, moss, and flip, which would be stretched sss-aaa-t, mmm-ooo-ssss, and fff-lll-iii -p. After the rubber band is stretched as far as it can go and all of the phonemes have been drawn out, snap the band back together with a handclap. When students clap, they say the word. In this way, the phonemes are brought back together to make a word. For example, flip would be modeled ffff-llll-iiii-p, (clap) flip! Zap the Sounds After students stretch the word, teach them to zap the sounds. Later, when students are more in tune with paying attention to the sounds of a word, they won’t need to stretch. They’ll just zap. There are many possibilities for showing phonemic segmentation through physical actions. In Wilson Reading, students tap out sounds using the fingers and thumb. The kindergarten teachers I worked with taught zapping. Here's what it looks like. First say the word as you make a fist. Next, segment the word into the sounds you hear, pumping your hand and throwing out a finger for each sound you say. For example, the word it gets two pumps. The index finger comes out when you say /i/. The middle finger comes out when you say /t/. Finally, draw your fingers back into a fist, blending the sounds together, and saying the word. When giving words, it is important for you to say the word and have your students repeat it before the zapping begins. In this way, a model of the correct pronunciation of the word is given prior to sound segmentation, and your students have the opportunity to repeat that correct pronunciation. After all, a sound-letter speller can’t spell an unknown word correctly if it isn’t pronounced correctly. Here's an example of a teaching routine I ran during spelling time. If I used six or seven words, it took about five minutes. My instruction was direct, explicit, and fast paced. The point was to work in lots of practice so that the kids could master the technique. Once mastered, children could use it as an independent strategy for spelling and reading unknown monosyllabic words later in the year. In this lesson, we’ll pretend I'm working with a group of 2nd graders on r-controlled sound spellings. MW: This lesson is about spelling r-controlled sounds. What is this lesson about, everyone? Students: Spelling r-controlled sounds! MW: The /ar/ sound is spelled a-r. How is the /ar/ sound spelled, everyone? Students: a-r. MW: The /or/ sound is spelled o-r. How is the /or/ sound spelled, everyone? Students: o-r. MW: Watch me as I zap out the word stork. Stork! [Say the word and make a fist]. /s/ /t/ /or/ /k/ [Pump hand, putting out a finger for each phoneme]. Stork! [ Pull fingers back into a fist]. Watch! I’ll do it one more time [Repeat the process.] MW: Now I am going to spell each sound with a letter or a group of letters. [Write letters as I say the sounds.] Now I go back and check by reading the word. Stork! MW: Now you try it. Your first word is card. Say it. Students: Card! [They make a fist.] Teacher: Zap it. Students: /c/ /ar/ /d/. [They pump their hand and throw out a finger for each sound, ending with index, middle, and ring fingers out. Then they draw their fingers back into a fist and say the word again.] Card! Teacher: Write it. [Pause while students write the word.] Teacher: Check your answer. The word card is spelled c, a, r, d. Correct your answer if you need to. If your word is correct and you want to put a star next to it, do so. [Students check, correct, and make a star] Teacher: Our next word is born. [Repeat routine.] Feel Your Chin Drop Hearing individual sounds and assigning a letter to each is not an especially efficient or manageable method for spellers encountering complex multi-syllabic words. Just think of trying to segment and spell the word kindergarten at the individual sound level, not the syllable level. But spelling at the pattern level, through syllables, is efficient and manageable, and by placing their hand under their chin, saying a target word softly and slowly, and counting the number of times their hand moves (which is equivalent to the number of times their chin drops), students can easily break words into syllables. Then they can stretch and/or zap the sounds in each syllable to spell the sounds. Still later, they can apply pattern and meaning knowledge to help them decide how to spell each syllable of an unknown word. To model the chin drop, place the tips of your fingers, with your hand palm down, firmly against the edge of your chin. Say the target word slowly but naturally. Start with long vowel words that cause a deep drop in your chin, words like time and phone. You can also say word parts or “nonsense” words, like ipe, ove, and ain. Tell your students how many times your hand moved and tell them why it moved: every syllable has a vowel and vowels make our chins move downward when we say them. Sometimes the movement is large and sometimes it’s small. By the way, this is why I greatly prefer the chin drop to the handclap. Mouths and chins move naturally and unerringly with syllables. Claps do not. Once you have practiced one-syllable words, move on to two-syllable words. Choose your words carefully. Words with long I and long O sounds are good places to start: silent, highway, bowtie, robot, and so on. Have your students repeat the words with you as they feel their hands move and their chins drop. Next say three and four syllable words –volcano, condensation. Finally, mix up the words, and after each pronunciation, ask your students how many syllables they felt. For older children or children more phonemically advanced, ask them to identify the second syllable in a three syllable word, or the first. All of this draws attention to the sounds in words at the syllable level. Summary With short bursts of repeated practice, your students will master the art of stretching, zapping, and chin drops in just a few weeks. If you regularly review these Hear and Spell the Sound strategies as needed, it will come as no surprise when later in the year, during independent reading or writing time, you see your students silently mouthing words with their hands under their chins or pumping their fists and throwing out their fingers. |

Mark WeaklandI am a teacher, literacy consultant, author, musician, nature lover, and life long learner.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed