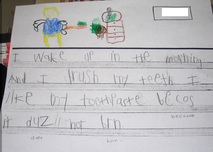

When it comes to understanding spelling and its role in literacy, my greatest leap forward occurred when I went back to the classroom to teach kindergarten, second grade, and third grade children. During this time, I was able to compare all of the “book learning” I had gained as a consultant with what actually happens with children as they learn to read and write. While teaching kindergarten students, I saw how young children take the sounds of language and turn them into the letter symbols of our English language. And I saw how they acquired reading, writing, and spelling skills at different rates, so that by the time kindergarten ended, some children were reading on an end of first grade level and writing entire paragraphs with many correctly spelled words, while others were just making the end of the year reading benchmarks and were writing simple sentences that showed basic sound-letter correspondence. And while teaching children in the corrective reading class, I saw how some older children had not yet “cracked the code,” even though they were in third and fourth grade, and I saw how the typical basal method of spelling instruction (fast paced sequence, weekly spelling test, worksheets) did little to move these children along in their spelling, writing, and reading achievement. My journey through the land of literacy has taken more than twenty years. And I have yet to arrive at a final destination. But I understand so much more about spelling instruction than when I first started teaching. In this blog post, I’d like to share some of what I have learned. My hope is that by sharing what took me decades to learn, I will help you shave years off the process of transforming your spelling program. Spelling ability does not develop from memorizing a weekly word list Spelling instruction should not be a weekly routine in which we give students a list of words, have them complete worksheets and write the words numerous times (so that they memorize the “look” of the words), and then give them a test at the end of the week where they regurgitate the words from memory. We all know some children (and adults) who seem to have a great visual memory for words. For example, my wife is someone who spells any given word by closing her eyes until the letter sequence of the word appears in her mind. Then she simply says or writes down the letters she “sees.’ However, this is not the way many of us spell. And research has shown that this is certainly not the way children spell. Spelling is not, and should not be taught as, an exercise in brute memorization. Spelling ability does develop from specific types of instruction How do we know that spelling is not an exercise in brute memorization? How do we know that there is more to spelling than recalling a letter sequence? One piece of evidence comes from research that has shown it is easier for children to remember predictable words than it is to remember irregular words (Treiman, 1993). Think about it. If spelling were simply an act of memorizing, it should be just as easy for kids to memorize the spelling of irregular words, such as want, does, and said, as it is for them to spell more predictable words like list, slap, and joke. The words just listed are all four-letter words, but we know from experience that first set is more problematic for children to spell. Some four-letter words are simply easier to spell than others! If your teaching a career has been anything like mine, then you have seen more than your fair share of want, said, and does spelled wunt, whunt, sed, sied, and duz. Thinking about my own spelling, if memorizing a letter sequence were all there was to it, then it should be just as easy for me to spell silhouette and ricocheted as it is for me to spell cannonball and instruction (all ten letter words). In the interest of full disclosure, it took me three tries WITH my spell check program to spell silhouette. Cannonball and instruction were not a problem. Research has also shown that children have a limited visual memory for letter sequence. I was surprised to learn that when spelling, a child holds only two to three letters in sequence (Aaron, Wilcznski, and Keetay, 1998). Thus, visual memory does not account for how our students spell four and five letter words, let alone multisyllabic words. Because children don’t typically spell by visually recalling a string of letters, the memorization of a standardized weekly word list is a practice that does little to help children learn how to spell. This begs the question, what type of instruction does help kids learn how to spell? As I said in my last blog post, the most effective spelling instruction is: • Systematic and sequential; • Direct and explicit (at times); • Focused and mastery-based; • Differentiated; • Strategy-based; • Centered on sound, pattern, and meaning. This is not to say that memorization plays no part in spelling. Certainly, some spelling involves committing to memory the specific letter sequence of a few irregular words, such as of, do, said, was, and once. And through varying amounts of repetition and practice, spelling is also the memorization of word patterns and rules (such as those governing the six syllable types or those governing aspects of meaning), which later can be accessed and used to spell unknown words. Finally, our ability to spell is improved when we can remember the “look” of a word because we has seen it many times through repeated exposure to words in reading and writing. But instruction that is focused and mastery-based, strategy-based, differentiated, and centered on sound, pattern and meaning, is something very different from instruction that is basically introducing, practicing, and then testing on a one-size-fits-all, memorize-and-move-on weekly spelling list. When we understand that instruction should be focused and mastery-based, we know that we should only introduce one or two spellings for a sound at a time, and that the introduction of sound spellings should unfold from the simple to the complex. Some core-reading programs introduce way too many sounds in one lesson (more on this later). And if ten of our first grade students have not mastered the spelling of short vowel sounds, then we should not be moving those students into the next set of spelling lessons which focus on long vowel sounds. Especially with K, 1, and 2 students, moving children too quickly through a spelling sequence leads to a lack of learning, a good deal of confusion, and the chance that guessing will become a habit. All of this can, in turn, lead to bigger problems in later grades. Our initial instruction should include many opportunities to slow down, step back, re-teach, and review, especially when we are teaching children who are in the early stages of spelling and reading development. When we understand that instruction should be differentiated, we know that because there is a continuum of development and achievement in our classroom, a rigid one-size-fits all spelling scope and sequence is not effective for all children. In November, in a classroom of 22 first grade children, there may be ten who have not yet mastered the spelling of short vowel sounds. There may also be five children in this classroom who easily spell short vowel sounds and are very capable of spelling multisyllabic words. This means the teacher needs to consider providing different words and different types of instruction to two or even three different groups of students. When we understand that spelling instruction should be strategy-based, we know that spelling instruction should not lead children and parents to believe that the only way to spell a word is to memorize it and then recall it when we need to use it in our writing. Rather, we know that spelling instruction should involve teaching the students a number of strategies that they can use independently to spell unknown words correctly right off the bat, get as close to the correct spelling of unknown words as often as possible, and notice and then fix-up spelling mistakes, fine-tuning any words that are “close” until they are exact, When we understand that spelling instruction should be centered on sound, pattern, and meaning, we know that spelling instruction should not lead children to believe that words are a string of letters, which can be memorized through a classroom activity that sounds like this: “The word is dumbfound. Spell it! D-U-M-B-F-O-U-N-D! The word is diphthong. Spell it! D-I-P-H-T-H-O-N-G! The word is discombobulated. Spell it! D-I-S-C… you get the idea. Rather, we know that spelling is orthography, which is generating a correct sequence of letters to create a specific word through a process that utilizes involves hearing sounds and assigning letters to them, thinking in terms of patterns found in words, and always cross-referencing what we hear and see with what the word means. Thus, our instruction leads children to understand that they can spell by listening to the sounds of a word and then applying single letters and groups of letters to each sound. Our instruction also teaches children that they can spell by remembering and applying letter patterns (or word families), such as –an, -ight, and –all, as well inflectional endings like –ing and –ed and common prefixes and suffixes like dis-, pre-, -tion, and –able. And our instruction teaches children to pay attention to meaning as they spell. When children get in the habit of thinking about meaning, they are more likely to spell homophones correctly, as in the sentence “Their dog was somewhere out there, lost in the forest,” or correctly spell the /t/ sound at the end of verb as –ed, as in the words helped, fussed, and plopped. Spelling is developmental For me, literacy is a wonderful blend of art and science: I enjoy practicing the art of motivating kids and getting a complex concept across to a classroom of students, and I also enjoy exploring the many fascinating theories that populate the field, including behaviorism, constructivism, reading as a transactional and metacognitive process, and spelling as a developmental skill. These theories – studied, debated, and discussed over many decades – allow me to move beyond intuition to a place where I can logically and scientifically understand how and why literacy skills develop in children. From there I can better understand how and when to use particular classroom instructional practices. To help us better understand what we see in our student spellers, and how we might best instruct those spellers, let’s consider the theory of spelling development for a few moments. When we understand that spelling is developmental, we know that all children acquire knowledge in stages about how they can use sound, letter patterns, and meaning to spell words. As Marcia Invernizzi says in No More Phonics and Spelling Worksheets, “… all students learning to read and write English experience these same developmental trajectories” (p. 22). But although all students experience the same paths of knowledge acquisition and skill development, different students travel these paths at naturally varying rates of speed. For this reason, we can expect to see varying levels of spelling achievement in a classroom, and we can begin to understand why a one-size-fits-all spelling program is not the best fit for any given classroom. It’s important to note that spelling development also varies according to our ability to effectively teach our students. At the start of every year, we can expect a variety of achievement levels. But as the year progresses, if achievement is occurring in some but not in others, it may be due to inappropriate instruction. I say may because there are, of course, many factors outside of school that impact student learning. But we can’t discount our own instruction. There’s no doubt that some instructional practices bring forth surges of achievement while others promote only modest or minimal gains. When we understand that spelling is developmental, we know that the mistakes students make on their spelling quizzes and in their authentic writing are not random, bizarre, or meaningless, but merely attempts to apply the knowledge they currently have about how spelling works. It takes a trained eye and a knowledgeable mind to understand where a student lies on the continuum of spelling development, but when we correctly place a child, we are in a much better position to help him achieve. Spelling instruction should stand alone, but should also be taught during reading and writing Teaching spelling well is something of an instructional paradox. Spelling should be taught as a stand-alone subject. During this stand-alone time, word study can occur, patterns can be explored, strategies can be explained and practiced, and word work activities can take place. All of this leads children to the mastery and control of word patterns, as well the understanding of how sound, pattern, and meaning come together to produce a correctly spelled word. Yet spelling should also be directly and explicitly linked to writing (including grammar) and reading (including vocabulary). This is because spelling and reading are two sides of the same coin (Ehri, 2000). The alphabetic principle is the idea that letters and letter patterns represent the sounds of spoken language. Conversely, the sounds of spoken language can be represented by single letters and letter patterns. During reading, we decode by looking at letters (graphemes) and then turning them into sounds. Typically we teach the graphemes for decoding in our phonics instruction. Spelling is other side of decoding and phonics. Spelling is encoding, or the turning of phonemes into graphemes, with the end result being standardized spelling for written communication. To spell, we turn sounds into letters. Because encoding is the flip side of decoding, spelling is a skill that supports more fluent reading. It does this because it serves as a second vehicle for delivering phonics instruction. It is also a tool that enables fluent writing. In turn, more reading and writing enable more fluent spelling. Reading widely exposes kids to more words and provides better background knowledge of how commonly used words are spelled. Writing widely does the same thing because when children write, they see words as they spell them, they see words as they revise and read their writing back, and they see words as they read their writing one last time, sharing it with a buddy, small group, or larger audience. It is important to remember that spelling is a means to an end, not an end in and of itself. Children do not spell so that we teachers can calculate a grade that goes on a report card. Children spell so that they can write. We can gauge the success of our spelling instruction by looking at our students’ fluency in writing. Is the act of writing becoming easier for them? Are they enjoying writing more? Are they able to write at increasing rates of speed? Do their writing samples show more and more correctly spelled words? Children also spell as part of the process of learning how to read. Thus, we can gauge the success of our spelling instruction by looking at our students’ reading fluency. Is their rate of reading picking up? Do they make fewer and fewer decoding mistakes? Are they able to use sound, pattern, and meaning to help them decode unknown words? If your answer to these questions is “yes,” “yep,” or “you bet your sweet bippy,” then your spelling instruction is working. What's Next Now that we know that spelling is more than a list and a test, we can put our knowledge to work and begin taking steps towards differentiated and developmental spelling instruction that teaches children how to spell, not what to spell. In my next post, I’ll discuss how to conduct quick and easy diagnostic assessments at the beginning of the year. These assessments will accomplish a number of things, including providing information on the overall “spelling health” of your class, pointing to areas of deficit for individual students, and offering possibilities for formative assessment as you move forward in the year. |

Mark WeaklandI am a teacher, literacy consultant, author, musician, nature lover, and life long learner.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed