|

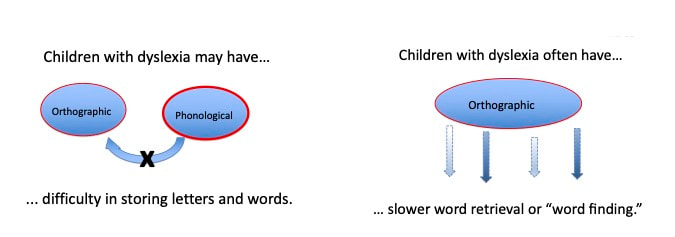

I have been presenting seminars on dyslexia for more than two years now, but the question “What is dyslexia?” still worries my mind. I want to make sure I'm getting it right! Some researchers, like Julian Elliot and Athansios Protopapas, say this: dyslexia is simply the far end of the reading achievement bell curve. They believe this lack of reading achievement is not neurobiological in nature (because evidence doesn’t support this conclusion), and labeling students as dyslexic is generally unhelpful, if not downright harmful. Meanwhile, professors like Andrew Johnson claim dyslexia is best understood as an ineffective use of meaning-making strategies (an idea also put forth by Constance Weaver) and disparage programs like Orton-Gillingham, saying they are unproven, overpriced, and ineffective. Statements such as these, however, are in the minority. Many more experts say this: dyslexia is a collection of traits, neurobiological in origin and arising from genetics, that lead to differences in the performance of reading-brain circuitry. In turn, these differences make it especially difficult for some people to learn how to read and spell and result in life-long challenges (of varying degree) in reading and spelling. Here is something else many experts say: direct, explicit, and systematic instruction - grounded in phonics, phonology, and fluency and focused on mastery learning - is effective in both preventing and overcoming many types of reading difficulties. For me, this stance sits on solid ground and reflects what I see and hear in the world of teaching.. Based on theories of reading built upon large bodies of evidence, the stance is anchored in the research of Bruce McCandliss, David Kilpatrick, Stanislas Dehaene, Gene Oulette, David Share, Mark Seidenberg, Mary Ann Wolf, and Linnea Ehri, to mention just a few. Importantly, this body of evidence points to these facts: 1) reading arises from the interaction of key brain processing areas (semantic, phonological, and orthographic), 2) the visual perception of correct letter sequences is the first thing to occur in the reading process, and 3) processing, strategy use, and opportunities to practice reading and writing collectively work to build increasingly skillful reading. Not only is this theory of reading (and the related theory of what dyslexia is and why it persists over time) backed up by evidence, it leads to many practical and effective classroom actions that can be used to teach the students who struggle the most, regardless of whether or not they are identified as having dyslexia or a specific learning disability. When these classroom actions are put in place, they prevent many reading difficulties from occurring. Not only that, if difficulties do occur, these actions help students to overcome their difficulties. Finally, when I travel around the country and ask teachers if programs like Heggerty Phonemic Awareness, Read Naturally, and Lindamood-Bell’s LiPPS are helping to move struggling readers and spellers forward, their answer is resounding YES! This is why I present dyslexia as being a learning difference that is neurobiological in nature and responsive to Tier I, II, and III instructional practices that stresses phonology, orthography, and fluency. What are some of these specific instructional practices? In the rest of this post, as well as a following one, I will give a variety, starting with PreK to First Grade. Here we go… PreK to First Grade For young students, one of the most important things you can do is teach phonological awareness to an advanced level. Aggressively teaching phonological awareness to an advanced level can help prevent reading difficulties from occurring, as well as help students overcome challenges if they do manifest. A sequence of necessary phonological skills includes the following:

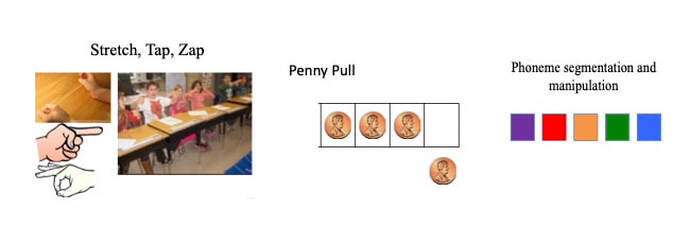

Phonological skills, from identifying and manipulating syllables and rimes to phoneme segmentation and manipulation, can be taught through a variety of activities and materials, including:

Assessments that give information on whether or not students have or are developing advanced phonology skills include:

In next week’s post, I’ll continue the above list of classroom actions, giving you activities for orthography (phonics-spelling) and fluency, kindergarten through 3rd grade. In the meantime, thank you, teachers, for the work that you do! Select Sources

|

Mark WeaklandI am a teacher, literacy consultant, author, musician, nature lover, and life long learner.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed