|

Source: Unsplash

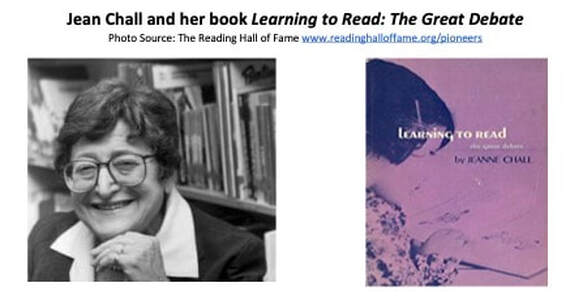

This post was specially written for MarkWeaklandLiteracy.com By: Reina Janice In recent years, digital technologies have occupied a huge space in education. For example, our post on using ‘The Slide Show to Build Language Comprehension’ talks about how a modern slideshow can convey so much information in an engaging way. Compared to previous decades, where available images could be limited or outdated, slideshows are a tool to add new words and their corresponding meanings to a child’s mental lexicon. Based on Maryville University’s description of American education, digital innovations are also rapidly transforming the way we approach learning. Around 21.1% of public schools offer at least one purely online course, while 90% of teachers believe that classroom technology is important to student success. However, 60% of teachers also report that they are “inadequately prepared to use technology in classrooms.” Many instructors need to keep up with shifts like swapping textbooks for tablets to effectively prepare students for a high-tech future. One area of concern, in particular, is whether or not reading in a digital format affects comprehension. Reading is not a natural skill, and it takes real work for us to master it. Unlike learning to talk, which we absorb by listening to others, the brain doesn’t have a special network of cells exclusive for reading. Instead, it borrows networks that evolved to do other tasks. For example, brain circuitry that evolved to recognize faces is used in reading to recognize letters. This flexibility is beneficial, but it can be a problem when reading different types of texts. When we read online, we use a different set of cellular connections from the ones we use to read in print. In this article, we’ll look at how reading in digital formats can affect comprehension and how to help students read across mediums. Reading a screen makes us faster readers – but not in a good way Reading on a screen often involves skimming, scrolling, browsing, and scanning. There is a sheer volume of content available online, which invites us to read quickly without going in-depth. As the University of Washington’s study on social media points out, we often enter a dissociative state when we scroll online and stop paying attention to what we’re doing, so sometimes we don’t even remember what we read on our phones. We’ve also gotten used to short reads like text messages or Tweets that don’t require much effort to understand. Living in a fast-paced digital world can change younger students’ brain plasticity and influence their ability to improve in comprehension, since the environment rewards shorter attention spans — even if we’re not absorbing ideas well. Digital reading can lead to shallow processing A research on smartphone reading published in Scientific Reports discovered that reading on a smartphone can promote brain overactivity in the prefrontal cortex, leading to poor narrative content comprehension and lower cognitive performance. It’s possible that the amount of digital stimuli — ads, updates, emails, texts — places a heavier visual load on our brains. In comparison, reading in print is less visually demanding. There are spatial and tactile cues that help us process the words on the page. For example, while reading in a digital format, readers can only navigate through text left to right and up and down. But a physical book gives spatial cues in three dimensions: left-right, up-down and forward and backward, across pages and entire chapters. Digital reading is also less likely to foster habits like reflection and note-taking, and a gap in these habits can limit overall comprehension. Some training is needed to read digital text effectively Researchers at the Complutense University of Madrid note that when eBook materials are properly selected and used, young children can develop literacy skills equally well and sometimes better than with print books. eBooks are more accessible, after all. Those with reading disabilities can adjust the font size, background color, and typeface for ease. And you can highlight the text, take notes, or visit links to additional resources. It just takes some training to better engage with digital text. For younger readers, they can try to summarize what they’ve read orally, while older children can reflect through writing. The key is to be mindful and strategic when interacting with whatever we read. Specially written for MarkWeaklandLiteracy.com By: Reina Janice I love reading. It informs me, whisks me away to other worlds, entertains me with gripping stories of love, adventure and redemption. I love science, too, because it thrills me with descriptions of billion year-old life forms and humbles me with deep-space photos of a million spinning galaxies. So, I was delighted to discover a few years ago something called the Science of Reading. “It’s science and reading combined,” I cried, “like sweet chocolate and peanut butter in a Reese’s Cup! What could be better?” But I must confess that lately, when I see that capitalized label stamped on book covers and classroom materials, I am surprised to hear my inner skeptic whispering words of caution. And I can’t help but think of that quote from the American philosopher Eric Hoffer: “What starts out here as a mass movement ends up as a racket, a cult, or a corporation.“ To ensure the Science of Reading avoids this fate, let’s consider how we present the science behind the teaching of reading. I’ll kick off the consideration by sharing two things on my mind: honoring our reading history and avoiding the bandwagon. Honor Reading History Scientists (aka researchers) have been shedding light on the subject of reading for a long time. This is true for both theories that describe what reading is and instructional practices that bring it into being. Sixty-five years ago, Harvard’s Jeanne Chall wrote Learning to Read: The Great Debate and the subject it surveyed was the fifty years of reading research that occurred prior to the book! Around now for at least 115 years, the science of reading is nothing new. That, of course, doesn’t mean reading science has nothing new to offer us. For me, the information bundled as the capitalized Science of Reading is exciting for a number of reasons. First, by highlighting the workings of the human brain (and the mind that arises from it), it brings new information and energy to old ideas. Second, by emphasizing particular aspects of reading, it makes effective instruction more possible, specifically because we have increased our focus on teaching phonology and orthography, using explicit and systematic instruction, and melding language comprehension and automatic word recognition. But although the capitalized label is relatively recent, much of the information that supports the Science of Reading (SoR) is not. Regarding the research that supports the movement, the work of (among others) Linnea Ehri, Philip Gough & William Tunmer, Jeanne Chall, and David Share goes back forty or more years. Also, many important areas of reading research that have lead to effective classroom practices are not officially part of SoR. These areas include studies on the transactional nature of reading, the importance of writing, the role of motivation in reading, the function of authentic and diverse books, and the value of differentiation. And here’s something else: just because a practice like literature circles or a philosophy like balanced literacy lacks science in its title, that doesn’t mean it isn’t based on some scientifically derived insight. Nor does it mean that the practice or philosophy isn’t worthy of classroom use. To summarize, the specific scientific ideas promoted by the Science of Reading, and the classroom practices that flow from this promotion, are tremendously important. But there are other important classroom practices to incorporate into our reading instruction and as an educator deeply involved with the lower case science of reading, I owe a debt of gratitude to the scientists who have brought forward all of these important practices. Beware the Bandwagon Also beware the cult and the pendulum swing. All are created when a group of people, from reading specialists to a school board or publishing company, too fully embrace a particular set of educational ideas while rejecting others. The end results include money wasted, conflicts created, teachers confused (and turned off), instructional effectiveness diminished, and worst of all, students who don’t learn what they need to learn. Recently I’ve been wondering if our field’s tendency to jump on a bandwagon is due in part to labeling. Any educational label – from guided reading and balanced literacy to the science of reading and structured literacy–collapses a rich body of thinking into just a few words. Thus, labels perform a useful function, allowing us to quickly grasp and remember the details of intricate, multi-faceted subjects. Perhaps labeling is part of our brains’ amazing ability to create schema: one thing is attached to another, which is also attached to another and another. Conjure up one strand and very quickly an entire tapestry comes into focus. But catchy labels are double-edged swords: they can lead to simplistic and fuzzy thinking, blind allegiance, and corporate greed, all of which can keep large numbers of children from learning how to read. Lucy Calkins, the well-known educator and creator of Units of Study, seems to have been effected by all three (as described in a 5/22/22 NYTimes article), embracing her own theories and data too fully, excluding other important data sets too completely, and concentrating too much on product production and not enough on product effectiveness. Perhaps this explains how and why a thirty-year giant in the field has only recently embraced the idea that teaching phonemic awareness and spelling-phonics to mastery levels is a critical part of any foundational reading program. Sadly but not surprisingly, the Science of Reading may be suffering from the same effects. Scroll through the #scienceofreading Twitter feed and you’ll see blindly allegiant Tweeters angrily tagging others as idiots, the enemy, or both. And recently a friend mentioned a meeting he had with an educator who demanded more fidelity to the Science of Reading message and more publications flying its banner. To my friend, the encounter felt “like a witch hunt.” As for money making, I have on my computer desktop The Reading League’s defining guide on the Science of Reading. According to the League, the Science of Reading is definitely NOT a program of instruction or a one-size-fits-all approach. But also on my desktop is a Science of Reading product, available from Teachers Pay Teachers, that very much looks like a program of instruction that feed a one-size-fits-all approach. Products such as these, each promoting their particular version of the Science of Reading, proclaim that balanced literacy “teaches with no pre-determined scope and sequence,” “presents spelling as if words are remembered by sight,” and “does not address orthographic mapping.” I know many excellent teachers, teaching in “balanced literacy” schools, who say nothing could be further from the truth! In a World of Riches, Why Be Binary? Sadly, our nation is plagued by divisions. Media reporting repeatedly uses the word “war” to describe our political, cultural, and economic differences. I don’t agree with the use of that term and I certainly don’t believe there needs to be some horrific struggle over how to teach reading. Rather, there is room for sharing and synthesis because we know what works. In fact, I see this sharing and synthesis all the time. The field of reading is blessed with more scientifically-derived support than any other elementary school subject area. Again- there is much agreement on what works. So don’t sweat the tiny details. And certainly don’t let anyone say you have to choose one side over the other: direct and explicit spelling-phonics over shared reading, small group skill work instead of guided reading, decodable text rather than engaging picture books. Pick the best parts of each, basing your picks on the needs of your students, giving some students more of this and less of that. Finally, regarding the Science of Reading, let’s do the following: 1) connect the current Science of Reading movement to the long history of science in the field of reading, 2) show how SoR works with other science-informed bodies of classroom practice, and finally, 3) work to keep its message respectful, nuanced, and positive. The end result will be more reading success for more students.

|

Mark WeaklandI am a teacher, literacy consultant, author, musician, nature lover, and life long learner.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed