|

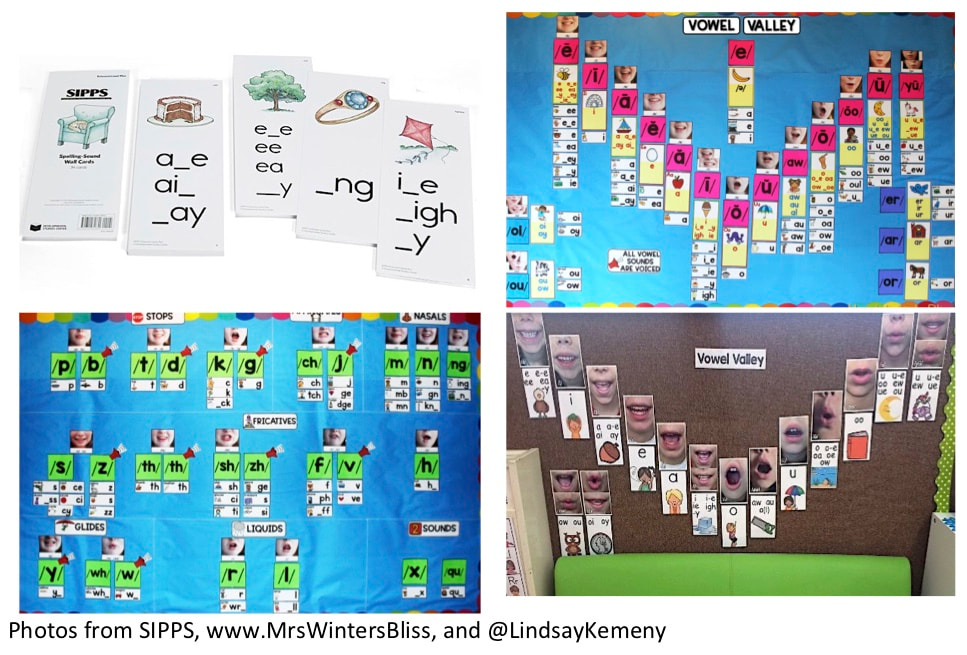

An editor friend recently alerted me to an Instagram posted by a teacher excited to unlearn an old habit. Previously the teacher had only presented letters to her young students and then asked, “What sound does the letter ___ make” and “What sound does this letter say?” Now her instruction often includes presenting a sound and then asking, “How do we spell the ____sound?” “Unlearning is the new learning” is a catchy phrase that reminds us it’s a good idea to replace old ways of thinking with new ones linked to more effective reading and spelling instruction. It’s great to hear of a teacher’s willingness to rub out old routines and replace them with new ones, and I include myself here. I’m glad my stubborn brain is still capable of leaving a rut and heading off in a different direction. In terms of brain circuitry, the processing areas that lead to reading are these: meaning, sound, and spelling. The language pathway (connecting meaning and sound) is one that wires itself and wires itself early. Sure, adults help strengthen this pathway as they interact with infants and young children, but no adult has to directly and explicitly teach a child to hear spoken words and associate them with meaning. On the other hand, the reading pathway must be wired and it is typically wired by teachers. Enter effective instruction. Any teacher exited to ask her students the question “How do we spell the ___ sound” is absolutely on the right track because letters were created to represent discrete sounds of language, not the reverse. Knowing that speech knowledge comes before print knowledge, it makes sense to teach sound-letter associations just as often as letter-sound associations. Also and importantly, when working with some reading disabled students, we may need to teach sound-letter associations very frequently and over a long stretch of time. A quick story: while proof-reading my new Corwin book, How to Prevent Reading Difficulties, PreK-3, I had an extended conversation with my copy editor about whether to use the term sound-letter association or letter-sound association. In my chapter on activities for teaching orthography, I had toggled back and forth between the phrases but to avoid confusing readers, we felt it best choose only one. I dearly wanted to use sound-letter because the term reflects the sequence of skill acquisition, #speechtoprint. But after scanning a slew of articles and websites, I clearly saw the most commonly used term was letter-sound association. As far as I could tell, Louisa Moats was the only researcher to semi-regularly use “sound-letter association” when talking about teaching young children the alphabetic principal. And so I decided to go with letter-sound. So much for unlearning! Looking back on it, I should have chosen sound-letter association. I could have been a trend setter! And I should have included more information on how to use sound walls to teach spelling-phonics. Hence this post. I first learned of sound walls (as opposed to word walls) about 15 years ago during a LETRS training (Louisa Moats and Voyager-Sopris). Sound walls are bridges, helping students cross from speech to visual representation, a.k.a. the letters and letter combinations that represent the 42 to 44 sounds of the English language and come together in specific sequences that make specific written words like shipwreck and kangaroo. Here are what sound cards and sound walls look like: By the way, the phonics program Jolly Phonics (developed in the UK) takes a sound-letter approach by using an expanded phonic sequence that includes all the sounds of the English language: s, a, t, i, p, n, c, k, e, h, r, m, d, g, o, u, l, f, b, ai, j, oa, ie, ee, or, z, w, ng, v, oo, y, x, sh, ch, th, qu, ou, oi, ue, er, ar. Interesting, right? And useful for teaching four to six year-old students many of the basic spellings of English language sounds. If you’re a teacher looking to transition from a word wall to a vowel and/or consonant sound wall, at the end of this post I've posted links to an informative article, a step-by-step sound wall construction guide, and three places to purchase sound cards. But first, a final thought. Students who have or may have dyslexia, often have difficulties processing the individual sounds of language (phonemes). This makes it difficult for their brains' to orthographically map letters onto sounds, as well as store word chunks and whole words in the spelling section of their brain dictionary (Wolf, 2008; Kilpatrick, 2015; Seidenberg, 2017). One way to support all students in spelling-phonics, but especially those who have or may have dyslexia, is to give them lots and lots of practice in analyzing phonemes and then associating those phonemes with letters and letter combinations through reading (decoding) and spelling (encoding). This may be one reason David Kilpatrick gives a shout-out to the LiPPS program (Lindamood-Bell) in his 2015 book. So, if you are a reading interventionist or Title I teacher working with students who have difficulties with automatic word recognition due to deficits in the phonological and orthographic processing areas, give some serious consideration to systematically teaching sound-letter associations with a sound wall! Here's a practical and helpful article about sound walls from one of my go-to websites, Reading Rockets:: www.readingrockets.org/article/transitioning-word-walls-sound-walls. Click this link for a step-by-step guide from Voyager-Sopris. Looking to purchase some sound-spelling cards to create a vowel and/or consonant sound wall? Here are some sources:

Citations

|

Mark WeaklandI am a teacher, literacy consultant, author, musician, nature lover, and life long learner.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed