|

To more effectively build students' foundational reading skills, help children build a storehouse of words in their brain, and teach this basic body of store-able words in in a way that is different than traditional "sight word" instruction. Over the last three years, as I have read the research and writing of Linnea Ehri, Mark Seidenberg, and Maryanne Wolf, I often found myself reflecting upon how words are really learned and read, and how the sight word instruction I gave to my reading impaired third graders and developmentally-typical kindergarten children was, at times, inappropriate and ineffective. In March of 2018, I wrote a blog titled “No More Sight Words.” Then, just this month during a spelling presentation and in an email response to a teacher, I found myself once again discussing sight word instruction. So I thought it appropriate for me to devote this month’s blog to the body of words that many call “sight words” and a few call “early automatic reading vocabulary words” (Rawlins & Invernezzi, 2019). But my preferred term is brain words, a term coined by Richard Gentry and Gene Ouellette in their book Brain Words: How the Science of Reading Informs Teaching (Gentry & Ouellette, 2019). I prefer the term brain words because I want to move away from the term “sight words," its associated meaning, and its associated method of word instruction: presenting high-frequency and “irregular” words on cards, four to five at a time, using instruction routines that force kids to rely solely on sight to move the words into long-term memory. I’m using quotes around “sight words” and “irregular" because as we will soon see, words such as when, said, all, and some aren’t solely learned through sight, nor are they outrageously difficult to decode (and thus they are not truly irregular). The term brain words more accurately reflects how foundational reading is brought about by the workings of our brain, which encodes words in the dictionary of the mind, and best-practice instruction that presents highly-usable words in activities that connect meaning, pronunciation, and spelling. Here’s what Gentry and Ouellette have to say about words and instruction: “Teaching students to read [is] about fostering developmental changes within each student’s brain that lead to improved reading. The missing piece of effective reading instruction enables the brain to become specialized for reading so that it can store brain-based spelling representations. This process is called orthographic learning, and the resulting brain-based representations are what we call brain words” (p. 3). As I have discussed in previous posts, Mark Seidenberg’s Eternal Triangle is my go-to model for understanding the foundational workings of the reading brain. The three points of his amazing triangle are sound, spelling, and meaning (or phonology, orthography, and semantics). When we consider the triangle in light of Linnea Ehri,'s research, we know that fluent word reading occurs when children immediately pronounce and understand the words they see. These instantly recognizable words are read from memory, with no need to sound them out (Ehri, 2005, 2014). In other words, they are brain words. All words recognized automatically are brain words. A brain word is stored in the brain’s dictionary, ready for instant use in reading (or writing) whenever it is seen on a list or in a sentence. It can, of course, be found on the Dolch list and the Fry list, but it can also be found on a word wall, in a picture book, on a spelling or phonic list, and in early chapter books found in your classroom library. Linnea Ehri’s research illuminates how words are stored in the brain through repeated opportunities to engage in a process that involves decoding (turning letters into sounds) AND attaching a meaning to the combined sounds. Unfortunately, some teachers try to get children to store words in their brain dictionary through instruction that looks and sounds like this:

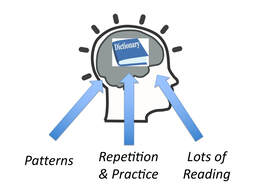

A week later the teacher presents five more words in the same manner. Then, a week after that, five more are given. At the end of the month, the teacher pulls the students aside, one at a time, and tests each child on the twenty words. What does she typically find? After four weeks of instruction, a few kids know most of the twenty, some know ten or twelve, some know only five, and one has failed to store any words. Presenting high-frequency words on cards to children and drilling them in a sight-based routine is something of a tradition in schools. Now, I am not necessarily knocking tradition. Traditions preserve history, foster togetherness, provide comfort, and build strength in a community or family. But some traditions hold us back and shield us from the truth. The traditional word instruction routine described above falls into the latter category. It is a practice that results in too little learning over too much time, it ignores the neuro-scientific truth of the reading process, and when students fail to master the 100, 200, or even 500 words their teachers are trying to cram into their heads, it causes worry and stress in the kids and their parents. The “learn it strictly by sight” method is problematic because it doesn’t make use of the way a human brain actually encodes written information. The human brain is a pattern recognition machine and a meaning making machine, and at its most foundational level it reads words through a seamless process of connecting sound, spelling, and meaning. This means that to efficiently and effectively teach children brain words - words that are instantly pronounced and understood when they are seen - we need instructional routines that:

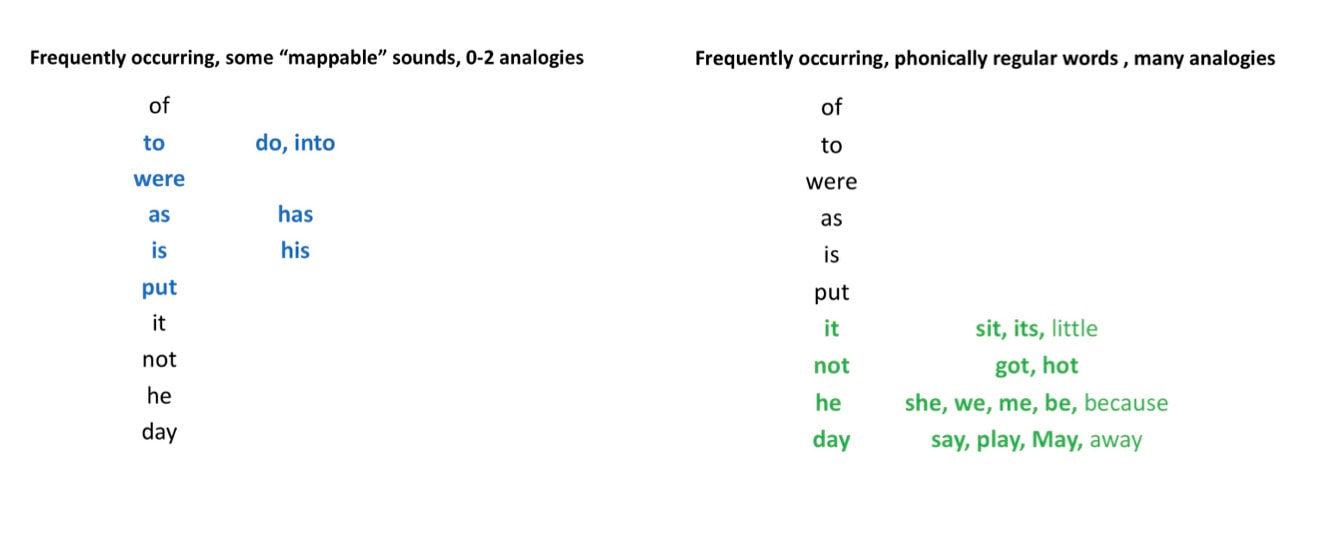

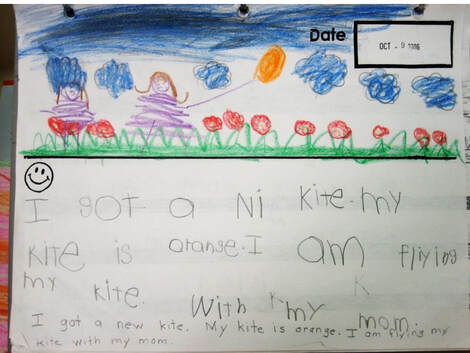

For example, the word ME is best taught by teaching a child to recognize the letters M and E, associating the sounds /m/ and /e/ with the letters, building the word from letter tiles or blocks, presenting the word ME in association with other similarly patterned words (such as BE, WE, SHE, and HE, as in the "Keys of e" shown below), reading the word in books, and writing the word in sentences such as “Look at me” or “My mom wants me to go to bed.” Many, if not most, high-frequency words contain highly mappable (phonetically regular) letter-sound associations. These associations often appear in analogous words that demonstrate the same pattern. Thus, most “irregular words” aren’t very irregular! One truly irregular word is OF. It has no analogies and thus no mappable sounds. But many other words, such as put and said have highly regular consonant pronunciations -it is only the vowels that are out of the ordinary. And so, a teacher can point out that the P and T in put is the same as the P and T in pot, pit, pat, and pet, just as the S and D in said is the same as the S and D in sad, sled, and slid. And most words on the Fry and Dolch lists, such as in, that, it, just, him, ask and day, contain totally predictable patterns found in many analogous words (like spin, cat, little, must, rim, little, and say). One last thing: teachers miss the boat when they concentrate too much on brain words that convey little meaning. These are the words of Fry’s First 100 Words, words like the, was, have, are, for and from. Rawlins and Invernezzi remind us that the research of Ehri (and others) has repeatedly shown that children learn concrete nouns, adjectives, and action verbs more readily than articles and prepositions. This means it makes more sense to emphasize words such as these: food, woman, water, people, run, play, happy, and big. These are the words we want to teach to the point of becoming brain words, for once children have a repository of brain words, they are ready for guided and independent reading and writing. In their excellent Reading Teacher article Reconceptualizing Sight Words (May/June, 2019), Amanda Rawlins and Marcia Invernezzi offer five helpful assertions that speak to word learning and teaching early readers (and I would add struggling readers). They are:

In conclusion, I encourage you to talk to parents and other teachers about how children best learn words and I challenge you to swap out the term "sight word" for the term brain word. And keep your eyes on the prize: promoting lots and lots of real world language comprehension and extended reading in school and at home. As Gentry and Ouellette say in Brain Words: “The more you read and study and experience life, the more words you add to that dictionary in your brain.” (p. 4). Articles and Books Cited and Referenced

|

Mark WeaklandI am a teacher, literacy consultant, author, musician, nature lover, and life long learner.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed