|

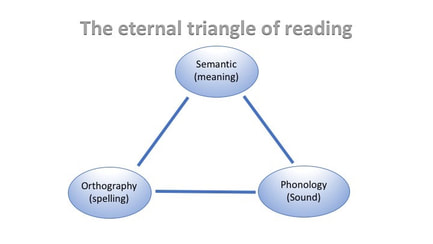

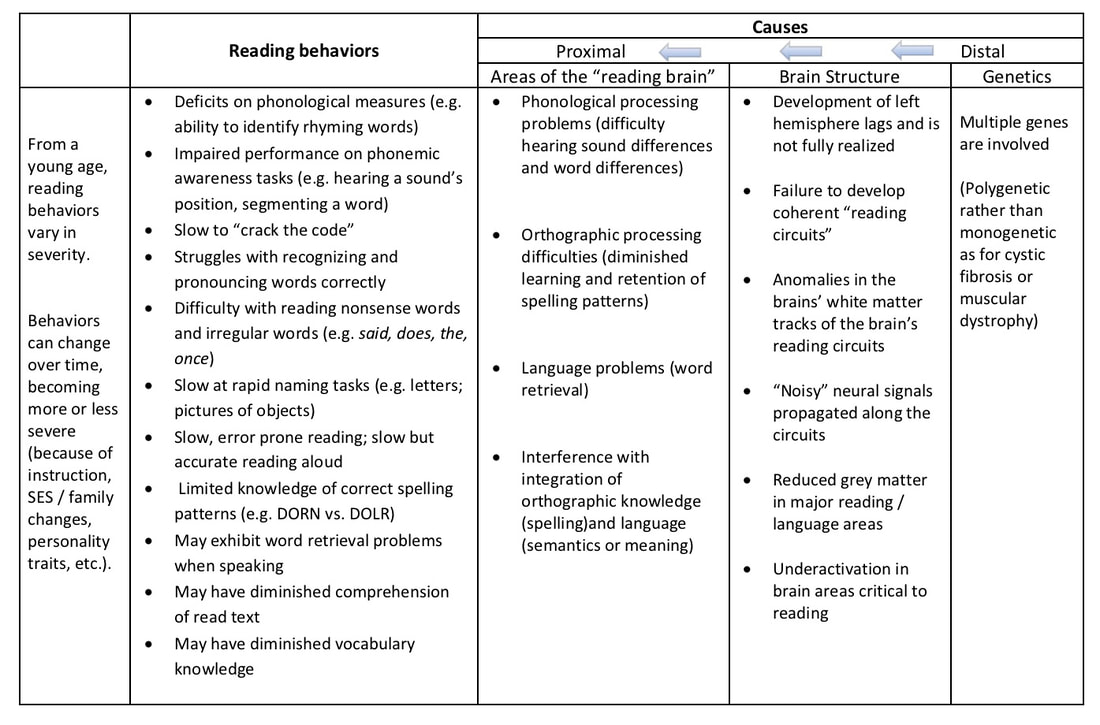

Mark Seidenberg's eternal triangle shows the fundamental elements of reading and gives a visual for the reading process. One reading pathway uses all three points of the triangle. This is the sublexical (decoding) route and it is wired through instruction that teaches young children phonemes, letter identification, sound-letter associations, and phonic/spelling patterns. Another pathway is the lexical, the reading circuit that utilizes whole words and flows between orthographic processing and semantic processing. As readers become more accomplished, this pathway is used more often because perceiving whole words and instantly connecting them to sound and meaning is more efficient than perceiving chunks, matching them to sounds, and blending everything into words. The eternal triangle also provides a way for us to understand how reading difficulties come about. When the points and pathways of the triangle are well developed and functioning smoothly, students experience fluent reading and accurate spelling. But underdeveloped and poorly performing points and pathways lead to deficits: slow and/or hesitant reading, errors while reading aloud, a lack of comprehension, a slow pace of writing, chronic spelling errors. Some reading difficulties are rooted in a lack of language comprehension. When a child lives in a language impoverished environment, she doesn’t hear and engage in word-rich conversations. This can lead to a dearth of background knowledge and vocabulary. Similarly, if her world is print impoverished, she won’t see written words, infer their meanings, or gain vocabulary through reading. Intellectual disabilities caused by birth defects or trauma can also impair language comprehension. Reading difficulties happen for other reasons. Dyslexia is a neurodevelopmental, brain-based condition that can lead to slow reading, word recognition errors, difficulty with phonemic analysis tasks, poor spelling, and slow and labored writing, among other things. Dyslexia begins with “glitches” in the genetic code. Evidence for this comes from observations of how the condition runs in families, passing from grandfather to father to son or daughter. Multiple genes are involved, but scientists don’t yet know which ones. Through the direct analysis of brain tissue, but mostly through functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), neuroscientists have gained evidence that the brain of a person with dyslexia has structure and circuitry that work differently than those of a typically achieving reader. Because phonology anchors written word learning and contributes to the act of word reading, problems with phonological processing lead to problems with word reading. It is difficult for a child with dyslexia to discriminate between sounds in a word. For example, it is hard for them to hear how words sound the same. Thus, grain and plane sound more different than alike. For kids with dyslexia, it is tough to learn the “chunks” of phonics and spelling. This, in turn, makes decoding and spelling more difficult. Impaired orthographic and phonological processing equates to poorly functioning reading pathways. Storing words in the brain dictionary is more difficult for children who have dyslexia, as is the retrieval of words that make it into storage. This leads to poor spelling as well as reading that is hesitant and error-prone. It’s like an older guitarist who can’t play a fluent solo because when he was younger, it was difficult for him to practice and play the scales. In this chart I have summarized information gleaned from Seidenberg, Shaywitz, and Wolf. It shows how the more distant causes of genetics and anomalous brain structures lead to processing problems in specific brain areas. These poorly functioning brain areas ultimately cause many of the deficit reading behaviors associated with dyslexia. THE REALITY OF DYSLEXIA “No single truth does not mean no truth.” - Iain McGilchrist We live in a time when observable facts, documented information, and scientific findings are not only questioned but are aggressively replaced by misinformation, false dichotomies, and downright lies. “Vaccines cause autism, its either jobs or the environment, climate change is a hoax and the earth is flat…” Good grief! Although debates about serious two-sided issues are healthy and necessary, and scientific truths often emerge only after decades of deliberation and argument, not all thoughts and ideas are worthy of equal consideration and, after a point, some are not worthy of consideration at all. When it comes to teaching reading, vast troves of information are available to answer questions about what constitute effective foundational literacy practices, why reading difficulties arise, and what teachers can do to prevent and correct them. Likewise, there is much evidence to support the idea that dyslexia is a biological, brain-based condition that affects how some children (and adults) think and learn, and that certain types of instruction help readers surmount difficulties caused by the condition. Dr. Sally Shaywitz said this almost fifteen years ago: “As a result of extraordinary scientific progress, reading and dyslexia are no longer a mystery; we now know what to do to ensure that each child becomes a good reader and how to help readers of all ages and all levels” (Shaywitz, 2005). Knowing the science of reading and the biological basis of some reading difficulties is tremendously important. Over the years I have talked with many parents whose children were having a hard time learning to read. These parents were distressed to see their children falling behind, upset when no one knew why their kids were struggling, and angered when they had to do battle with school systems that were unable or unwilling to assess their child fully and provide some kind of meaningful help. Unattended / unassessed dyslexia can be extremely difficult for kids, too. I have seen them frustrated, angered, and intimidated by their reading difficulties, and I’ve felt for them. If the educational community could straight up acknowledge dyslexia, it would accomplish a number of important things. First, children would be in a better position to understand themselves and not engage in blaming themselves for their difficulties. As they grow older, they could play to their strengths and work around their weaknesses. Knowing that dyslexia is a real condition helps parents, too, because they can better help their kids navigate their feelings and struggles. Finally, acknowledging dyslexia and educating others about it would help teachers understand how to instruct their students, both generally and specifically, and support children with dyslexia as they engage in the difficult task of learning to read. Acknowledging the truths of dyslexia allows us to move on to the business of “preventing and overcoming reading difficulties.” (Kilpatrick, 2015). And we need to get moving because the times in which we live demand action on many fronts. Concerning dyslexia, one action is using foundational literacy instruction that can be used to both prevent many reading difficulties and overcome them. This instruction is grounded in both science and common sense, logically arrived at, relatively easy to implement, and far removed from “pendulum swings” and “paradigm shifts.” In general, this type of instruction addresses the needs of many children, not just those with reading difficulties, takes place in general classrooms, and with some tweaking and connecting, functions in Tiers II and III as well. Also, it need not be program-based. More specifically, the instruction that prevents and overcomes reading difficulties (regardless of whether they arise from dyslexia), includes building language comprehension and background knowledge, as well as regular doses of phonemic awareness instruction (and more for those who need it), lots of phonics and spelling instruction, and many opportunities to read extended text (during all types of reading times, such as guided, independent, literature circles, and so forth). Here I want to clearly state that teaching kids phonics and teaching kids “reading” are in no way antithetical and attempts to frame reading instruction as a war between two camps is misleading and unhelpful. Teaching is inclusive, not exclusive. Thus, in all grades, kids are learning to read and reading to learn. There is decoding and encoding instruction (sometimes a lot of it) as well as metacognition and meaning instruction. And many opportunities for extended reading are present so that kids can practice their reading skills, and here I am talking about both phonics and meaning-making skills. There is too much ideological and binary thinking in our world. This is why I am dreaming of informational books devoted to literacy instruction based on multiple areas of theory and comprised of science-based, positive, and practical teaching actions that work with both whole groups and small groups, with young children and older children, and during dedicated phonics/spelling time and extended reading time. These practical actions form a foundation of basic classroom instruction as well as the bones of specialized interventions for those children who need them. In conclusion, dyslexia does exist. In the words of Dr. Timothy Shanahan, “There is a group of learners whose struggles to read are not due to any environmental problem or crummy parenting/teaching or low intelligence… These individuals, for some organic or developmental reason, can’t master reading without extraordinary effort. Whatever is disrupting the learning of these kids is within them, not around them.” The sooner we get onto the business of acknowledging truths about reading difficulties and dyslexia, and the sooner we take science-based action, the sooner we can take some weight off the shoulder of kids with dyslexia and help make their extraordinary reading efforts easier. (Thanks to Tori Bachman for inspiring this post) Citations and References

|

Mark WeaklandI am a teacher, literacy consultant, author, musician, nature lover, and life long learner.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed