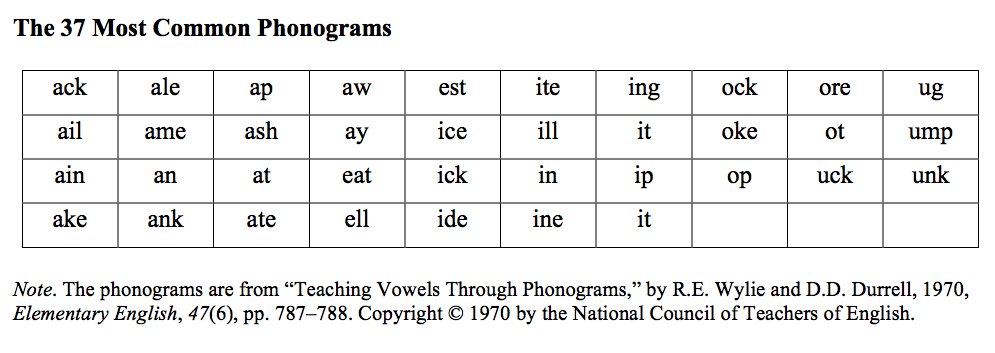

A quick and engaging activity, Look Touch Say is a nifty way to practice syllable types, spelling patterns, word definitions, Latin roots, and much more. Because it constantly cycles back to the basics of what you want to teach, it promotes mastery learning. And because it’s a short routine, taking only two to three minutes, it makes for a good warm up prior to word building or word dictation activities. I’ve modified and adapted it over time so I can use it in a variety of situations. Once you become familiar with it, I think you’ll find yourself doing the same. First, let’s look at using Look Touch Say as a way for younger children to practice common spelling patterns, and let’s discuss manipulatives rather than a word list as the material for teaching. To start the activity, decide on the patterns you want to teach and/or review. Patterns can be considered as chunks (ate, ain, eep, etc.,), vowel teams (ee, ai, oi, igh), syllable types ( r-controlled, open, closed), inflectional endings (ing, er, ed), and so on. Plastic tiles, magnetic tiles, foam blocks – anything will do. The materials I used with kindergarteners and third graders came from companies such as Step By Step Learning, Touchphonics, and Wilson Language, but you can, of course, make your own materials. Let’s imagine it is November and you are teaching first grade. Let’s also imagine you have been using the 37 Most Common Phonograms chart (mentioned in my last blog) as your scope and sequence. Last week’s lesson focused on short o patterns: ock, op, ot. This week your focus is short U patterns: ug, ump, unk. To reinforce the spelling of the patterns, as well as to have students notice the differences in the sound and spelling of the patterns, you decide to do five minutes of Look Touch Say. Here is a routine and a script for the activity: Have the students place the patterns in a row on their desks. Pick a pattern, such as ump, and say, “Look for ump.” Follow that command with “Touch it.” At this point, the students should only be scanning for the word part and then touching it with their index finger. Monitor their touches and guide and correct anyone who has made an error. After two to five seconds, depending on the age and ability of your students, the number of manipulatives on their desks, and how much monitoring and correcting you are doing, give the command, “Say it!” At this point, the students should say the word part. After praising their attentiveness, go to the next pattern. The routine is merely a repeated cycle of commands, which sounds like this:

The Look For and Touch It commands give children think time. As you scan the room, wait until every child as found the word. Only then say, “Say it!” You can also mix in the command “Spell it”:

Another variation is Look, Touch, See, Say, Spell. In this variation, you incorporate the all-important strategy of seeing the word (or in this case the pattern) in your head. But be careful: this sequence might be too much for young students.

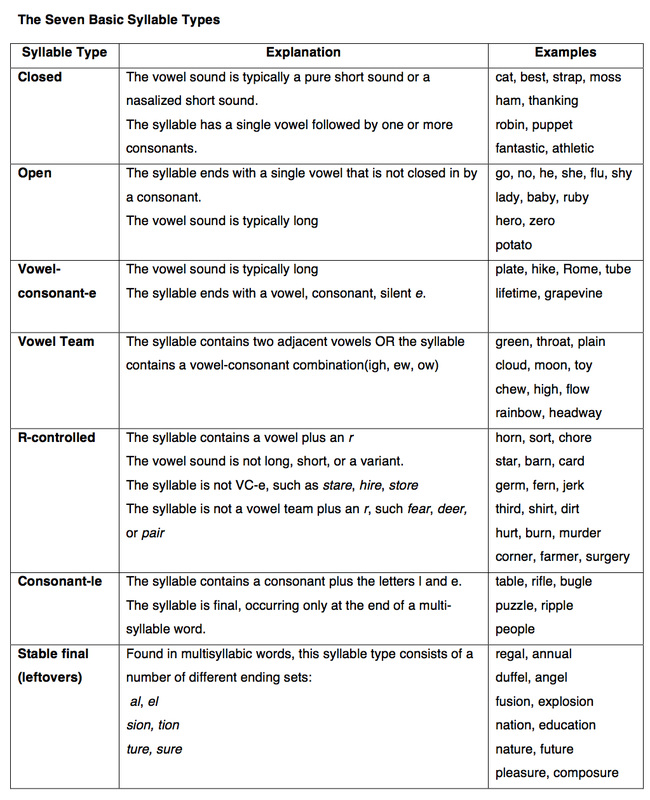

You can also work in commands that are more open ended. For example, you might say, “Look for a pattern with the /ŭ/ sound.” In this case, when you give the “Say it” command, some students might say unk, some might say ug, and some might say ump. This variation is not for teachers who like orderly and uniform responses! But it you’re okay with a bit of chaos, try it out. Now let’s consider doing Look Touch Say with older students, and this time using a word list or word cards. Pull a subset of words from your master list, print the subset as a list, and give the list to the large group or small group of students you are working with. It might look like the list below. Or you can have the kids put the words onto cards that can later be used for pattern sorts. First, review the words by simply saying, “Look for fruit.” Quickly follow that with “Touch it” and after a pause, “Say it.” Next might be “Look for nephew.” “Touch it.” [Pause] “Say it.” This type of direct and explicit review, cycled over and over again, can be especially helpful to ESL students or students in special education, who need practice and repetition in seeing and saying words. Next, move to noticing patterns. For example, you might say, “Look for a word with the ing pattern.” “Touch it.” “Say it!” Here all the children would say, “bruising.” But if you were to say, “Look for a word with the vowel-consonant-e pattern,” then different children would touch and say different words. You might follow up their response with “Very good! I heard some say huge, some say flute, and others say suitcase. Those are all correct. Each has the vowel-consonant-e pattern.” Add a bit more by saying and asking the following: “Look at huge and flute. How are they alike? What long vowel sound is produced in those words? How is it spelled? Look at suitcase. Is that word similar to huge and flute in any way? How is it different? How many long vowel sounds are in that word? How are those sounds spelled?” You can also think in terms of syllable types rather than patterns. For example, you might say, “I’m thinking of a word with an open syllable. Look.” After the students look over their spelling list, say, “Touch.” Students then touch a word with appropriate syllable, in this case produce (the open syllable is pro). Or you might say, “Look for a word with a vowel-consonant-e syllable,” which leads to students pointing to and saying either suitcase or, more subtly, produced. Finally, bring meaning into this routine. Start simply, with a simple word definition routine such as “Look for the word that means discolored skin that comes from an injury” (bruise) or “Look for a word that means the son of one’s brother or sister” (nephew). Next, move to something more conceptual in nature, such as inflectional endings. A command for an inflectional ending might be “Look for a word that happened in the past.” “Touch it.” [Pause] “Say it.” Here the students would respond, “Produced.” This might be followed with a quick review of the inflectional ending, its meaning, and the principle for spelling it., which might sound like, “What spelling ending tells us an action happened in the past?” After the children respond with “ed,” you might say, “And what is our rule for adding an ending, like ed, to a word that already ends with e?” I have found that students learn the Look Touch Say routine quickly. Soon they will be ready to mimic it back to you. When this is the case, ask for a volunteer to lead others using a word he or she has picked. Still later, buddy children up and have them practice in pairs, or put the routine on your “I Can…” list and allow children to work with each other during your small group / guided reading time. Good luck and have fun! Once students regularly apply letters and groups of letters to sounds, they are ready to move on to recognizing and applying letter patterns within words. When students are in this stage of spelling development, they are ready for the strategy of spelling by analogy. This pattern-based strategy is appropriate all spellers at all stages of development. Use a Word You Know: The Spell By Analogy Strategy Put into kid friendly language, with an exclamation point for added emphasis, spelling by analogy is “using a word you know to spell a word you don’t know!” Spellers who use this strategy ask questions such as “Does the word I want to spell sound like a word I already know” and “Can I use a pattern from a word I know to spell a word I don’t know?” When students ask these types of questions, they are paying attention to not only to the sounds of words, but the patterns within words as well.. Paying attention to patterns is very important because when children pay attention to and remember patterns in words, they can use their acquired knowledge of known words to spell unknown words. For example, a child who has studied and learned tile and mile can use knowledge of the ile pattern to spell the words file and revile. Likewise, knowledge of the Latin root ject can be used to spell the unknown words project and object. By combing all this knowledge, a child spell an even longer word, such as projectile. On the flip side, readers can use their spelling by analogy skills to read unknown words. As I pointed out in previous posts, spelling is for reading! When students encounter a host of patterns in a multitude of words, they build up the dictionary in their brains, a dictionary that is critical to fluent reading. For example, the word guile is decodable if a student is familiar with the ile pattern from words such as tile and smile, and the sound of gu in words such as gun, gut, and gum. At a more advanced level, the word quatrain is decodable if a readers knows the word train and can recall a known word such as quad to help him decode the qua chunk. Here’s the spelling by analogy strategy. Teach it and students will have a plan for spelling unknown words:

Spelling by analogy – using patterns in known words to spell unknown words – is taught and developed when you model the strategy in your instruction, and when you give students activities such as Look Touch Say, word sorts, and word dictation. When modeling how to spell by analogy, use a think aloud to bring your inner thinking to light. You might say something like this to a class of first, second, or third graders (for older students, use the same type of modeling but pick more advanced words).

By the way, you’ll notice at the beginning of this little script, I reference the sound-based strategies from my last post, and then towards the end I touch upon the not-yet-discussed strategies of “Seeing the Word in Your Head” and “Circle the Word and Fix It Later.” In a one-syllable word, the spelling pattern that consists of the vowel and all the letters that follow it is known by any number of names, including chunk, family, and, if you’re a linguist, rime. Regardless of what it is called – chunk, family, rime – a spelling pattern like ack or ile helps students understand how words work and how patterns can be used to create words. You may be familiar with the 37 common spelling patterns or phonograms that many first grade teachers present to young children (see below). These patterns can be used to create hundreds of words. An even more powerful organizational scheme for spelling patterns is the seven syllable types (see the end of this post), which I hope to discuss at length in the future. One last thing about teaching students to spell by analogy: it makes sense to fold in instruction on spelling rules or principles . In Chapter 3 we discussed how some rules, such as “the position of a sound often determines its spelling” or “drop the e and add the ending,” are broadly applicable. For example, many sound spellings are position dependent, including /oi/ (toil and toy), /ou/ (out and how), and /s/ (sad and mess). In each case, the spelling of the sound depends upon whether it is heard at the beginning of a word or the end of the word. The /k/ sound is another example. Although sometimes spelled with a k at the beginning of a word (e.g. kite, kale, kitten), a beginning /k/ sound is more likely to be spelled with a c (cat, crazy, cantaloupe), and is never spelled with a ck, which is a spelling reserved for the end of a short-vowel, one-syllable word (e.g., tick, black, snuck, crock, backpack). The point about principles is that like the patterns themselves, spelling principles are specific, stable, and predictable over a large numbers of words. If you repeatedly present them and model their use, your students will begin to see how the majority of word spellings are both knowable and unsurprising. As Louisa Moats says, “These principles provide a framework for understanding those seemingly endless lists of rules that have given English spelling its bad reputation." Pg. 20 in Lousia Moats’ How spelling supports reading: And why it is more regular and predictable than you may think. American Educator, 29(4), 2005. Wrap Up In two to three weeks I’ll post a classroom activity – Look, Touch, Say – that helps students develop their ability to use both sound-letter strategies and the spell by analogy students. Until then, I wish any teacher reading this post a great start to the new school year and the best with your teaching! |

Mark WeaklandI am a teacher, literacy consultant, author, musician, nature lover, and life long learner.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed