|

Once students regularly apply letters and groups of letters to sounds, they are ready to move on to recognizing and applying letter patterns within words. When students are in this stage of spelling development, they are ready for the strategy of spelling by analogy. This pattern-based strategy is appropriate all spellers at all stages of development. Use a Word You Know: The Spell By Analogy Strategy Put into kid friendly language, with an exclamation point for added emphasis, spelling by analogy is “using a word you know to spell a word you don’t know!” Spellers who use this strategy ask questions such as “Does the word I want to spell sound like a word I already know” and “Can I use a pattern from a word I know to spell a word I don’t know?” When students ask these types of questions, they are paying attention to not only to the sounds of words, but the patterns within words as well.. Paying attention to patterns is very important because when children pay attention to and remember patterns in words, they can use their acquired knowledge of known words to spell unknown words. For example, a child who has studied and learned tile and mile can use knowledge of the ile pattern to spell the words file and revile. Likewise, knowledge of the Latin root ject can be used to spell the unknown words project and object. By combing all this knowledge, a child spell an even longer word, such as projectile. On the flip side, readers can use their spelling by analogy skills to read unknown words. As I pointed out in previous posts, spelling is for reading! When students encounter a host of patterns in a multitude of words, they build up the dictionary in their brains, a dictionary that is critical to fluent reading. For example, the word guile is decodable if a student is familiar with the ile pattern from words such as tile and smile, and the sound of gu in words such as gun, gut, and gum. At a more advanced level, the word quatrain is decodable if a readers knows the word train and can recall a known word such as quad to help him decode the qua chunk. Here’s the spelling by analogy strategy. Teach it and students will have a plan for spelling unknown words:

Spelling by analogy – using patterns in known words to spell unknown words – is taught and developed when you model the strategy in your instruction, and when you give students activities such as Look Touch Say, word sorts, and word dictation. When modeling how to spell by analogy, use a think aloud to bring your inner thinking to light. You might say something like this to a class of first, second, or third graders (for older students, use the same type of modeling but pick more advanced words).

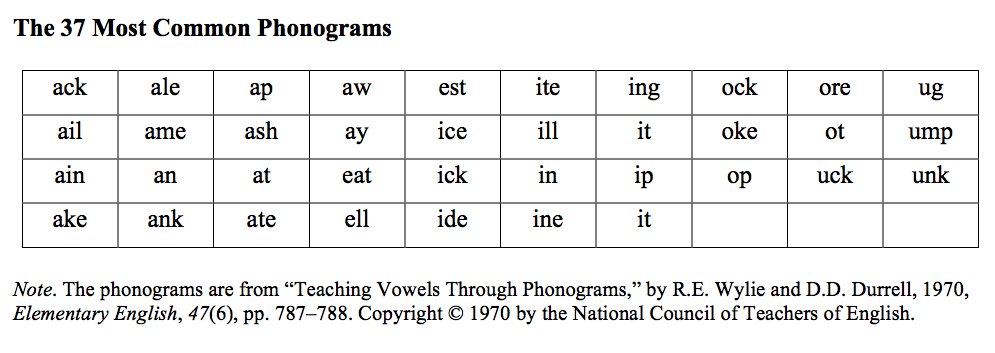

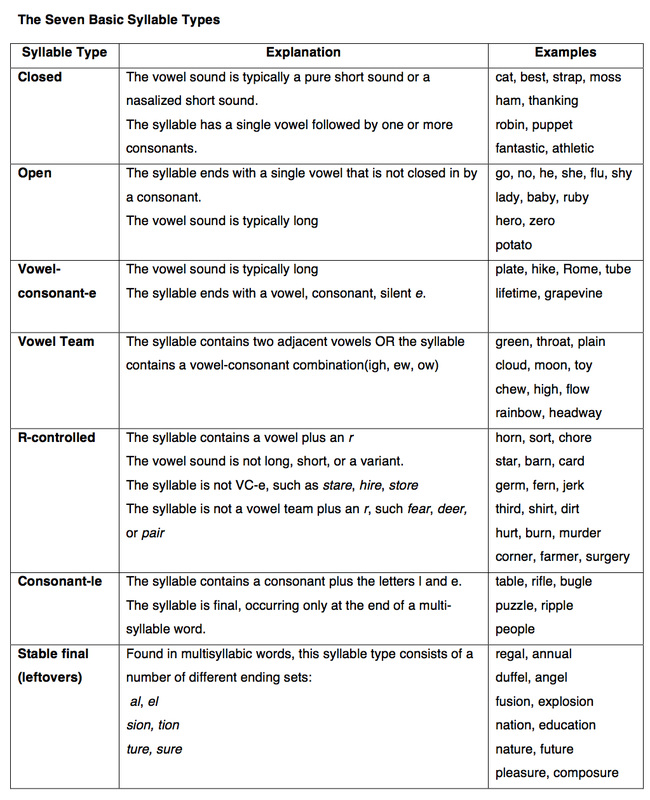

By the way, you’ll notice at the beginning of this little script, I reference the sound-based strategies from my last post, and then towards the end I touch upon the not-yet-discussed strategies of “Seeing the Word in Your Head” and “Circle the Word and Fix It Later.” In a one-syllable word, the spelling pattern that consists of the vowel and all the letters that follow it is known by any number of names, including chunk, family, and, if you’re a linguist, rime. Regardless of what it is called – chunk, family, rime – a spelling pattern like ack or ile helps students understand how words work and how patterns can be used to create words. You may be familiar with the 37 common spelling patterns or phonograms that many first grade teachers present to young children (see below). These patterns can be used to create hundreds of words. An even more powerful organizational scheme for spelling patterns is the seven syllable types (see the end of this post), which I hope to discuss at length in the future. One last thing about teaching students to spell by analogy: it makes sense to fold in instruction on spelling rules or principles . In Chapter 3 we discussed how some rules, such as “the position of a sound often determines its spelling” or “drop the e and add the ending,” are broadly applicable. For example, many sound spellings are position dependent, including /oi/ (toil and toy), /ou/ (out and how), and /s/ (sad and mess). In each case, the spelling of the sound depends upon whether it is heard at the beginning of a word or the end of the word. The /k/ sound is another example. Although sometimes spelled with a k at the beginning of a word (e.g. kite, kale, kitten), a beginning /k/ sound is more likely to be spelled with a c (cat, crazy, cantaloupe), and is never spelled with a ck, which is a spelling reserved for the end of a short-vowel, one-syllable word (e.g., tick, black, snuck, crock, backpack). The point about principles is that like the patterns themselves, spelling principles are specific, stable, and predictable over a large numbers of words. If you repeatedly present them and model their use, your students will begin to see how the majority of word spellings are both knowable and unsurprising. As Louisa Moats says, “These principles provide a framework for understanding those seemingly endless lists of rules that have given English spelling its bad reputation." Pg. 20 in Lousia Moats’ How spelling supports reading: And why it is more regular and predictable than you may think. American Educator, 29(4), 2005. Wrap Up In two to three weeks I’ll post a classroom activity – Look, Touch, Say – that helps students develop their ability to use both sound-letter strategies and the spell by analogy students. Until then, I wish any teacher reading this post a great start to the new school year and the best with your teaching! Comments are closed.

|

Mark WeaklandI am a teacher, literacy consultant, author, musician, nature lover, and life long learner.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed