|

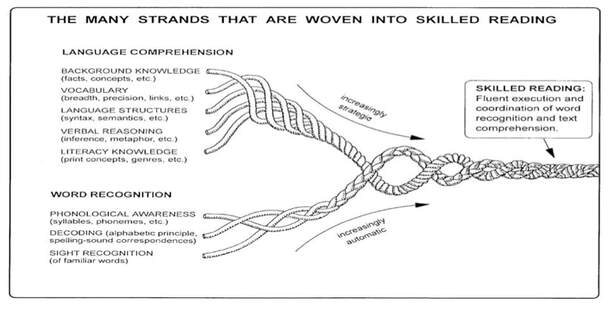

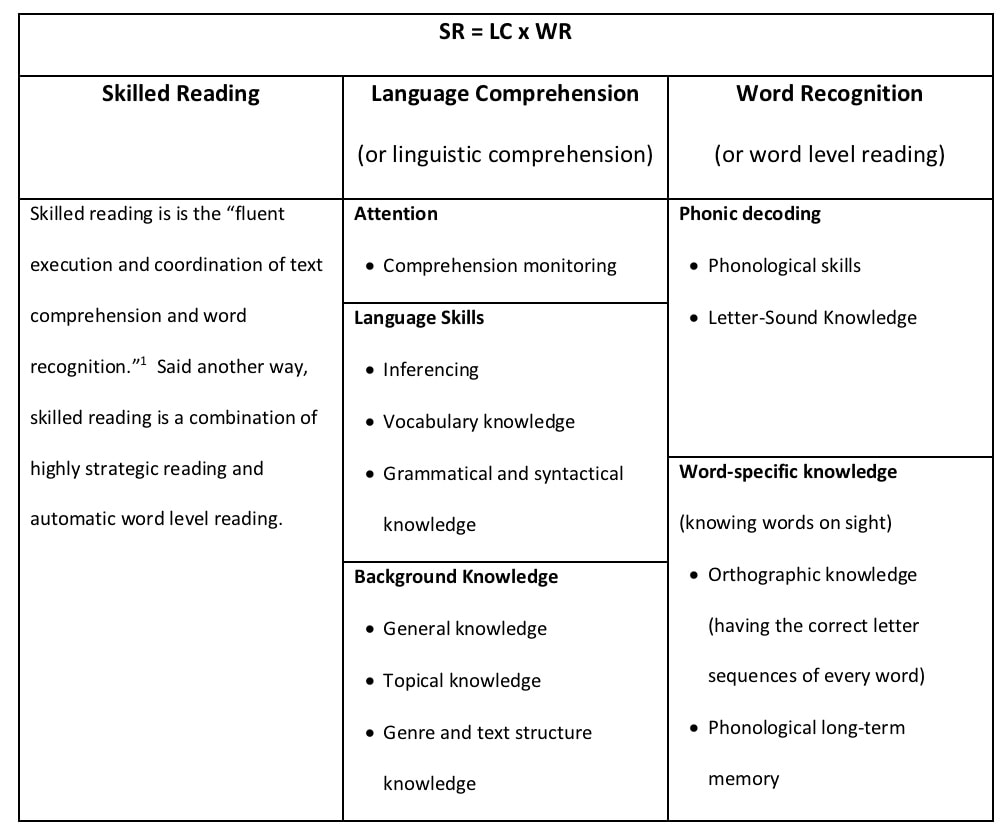

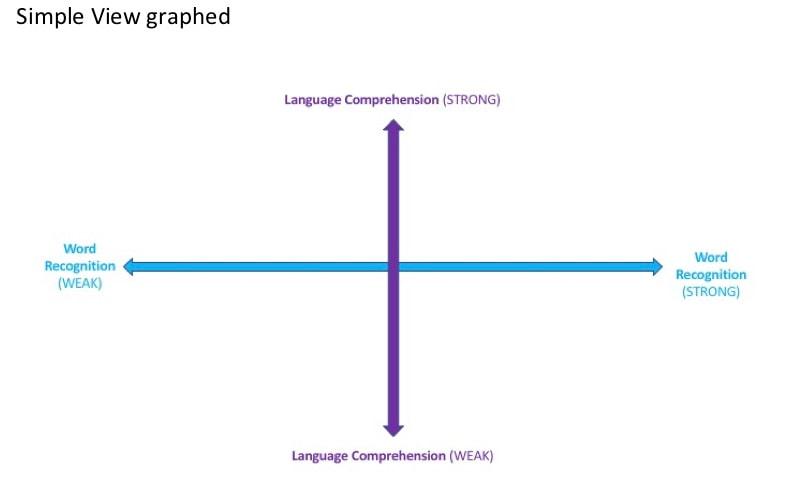

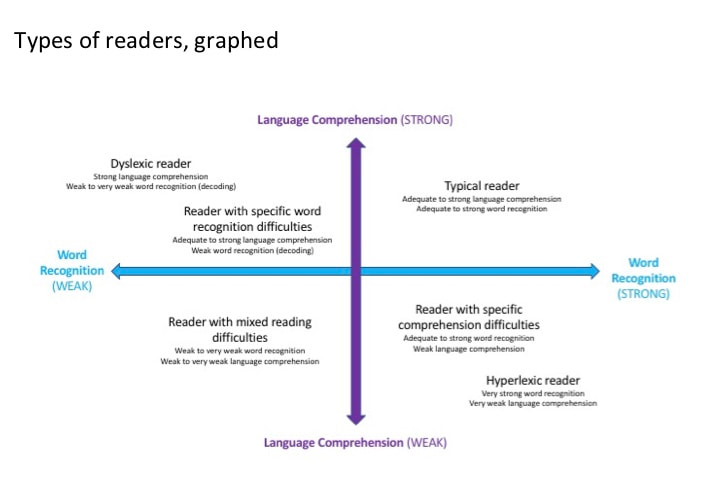

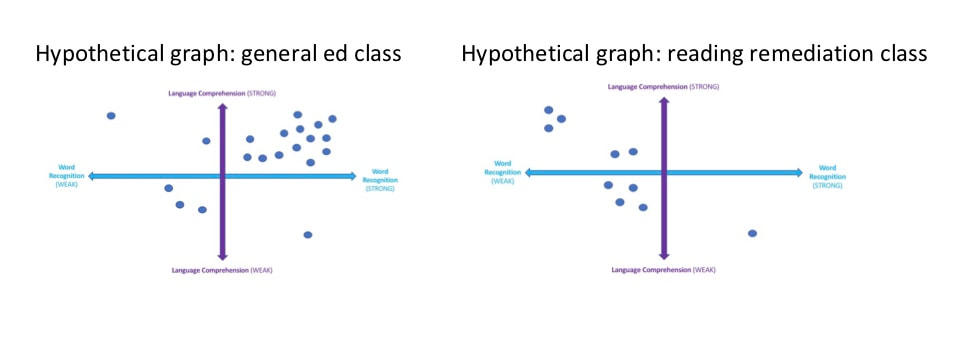

Reading involves identifying letters, mastering sound-letter associations, combining letters into phonic “chunks,” learning word meanings, reading through every word on a page, making connections between text ideas, understanding genre, employing strategies to stay on task, and much more. In other words, reading is complex! Are there simple ways of entering into the complex world of reading theory? For sure. In earlier blogs, I presented the Eternal Triangle, which describes the foundations of the reading process through three terms: semantics, orthography, and phonology. Amazingly, these terms can be condensed even further. The Simple View of Reading The formula that is the Simple View of Reading was put forth more than 30 years ago in a seminal article entitled “Decoding, Reading, and Reading Disability.” Then, reading researchers Philip Gugh and William Tunmer proposed the following equation: R = D x C. In other words, “…reading equals the product of decoding and comprehension” Over time, this elegantly described process of reading has come to be understood in increasingly nuanced ways. Thus, the formula’s terms and definitions have changed a bit. For example, shortly after the National Reading Panel released its report in 2000, Dr. Hollis Scarborough[ii] presented the Simple View of Reading as a braided rope, constructed of two main strands, each consisting of numerous threads. Anchoring her innovate and illuminating graphic is a slightly-tweaked formula: SR = LC x WR. Here SR is skilled reading, LC is language comprehension, and WR is word recognition. Later, in 2015, David Kilpatrick wrote the Simple View’s equation as R = LC x D, where LC equals linguistic comprehension and D is actually word-level reading[iii]. He then broke down the two variables – linguistic comprehension and word-level reading - into components and sub-components, all of which overlap and interact in complex and interesting ways. The chart below provides a synthesis and a summary of most, but not all, of the components and subcomponents of the Simple View of Reading according to Scarborough and Kilpatrick. When I look at the chart, I realize the Simple View of Reading is really not so simple! Nonetheless, Scarborough’s and Kilpatrick’s organizational schemes help me in my quest to understand why many children experience varying degrees of difficulty while learning to read. Because narrowly defined skills influence the development of broader ones, small problems often beget big ones. For example, if a child fails to develop strong phonological skills, especially in the area of phoneme analysis, her ability to map letters onto sounds is diminished. In turn, word-level reading is diminished and this ultimately leads to deficits in reading comprehension. Likewise, if a child lacks knowledge about words (vocabulary knowledge) and the world (background knowledge), her language comprehension is diminished. In the end, this leads to deficits in reading comprehension. I love the Simple View of Reading for many reasons. First, research has widely supported the ideas inherent in the model. Second, the Simple View reflects the same reading process described by the Eternal Triangle. The two inform one another. Third, the equation is a clean, straightforward way for teachers like me to enter the intricate world of reading theory, including how reading works, how reading can be assessed, and how reading can be instructed. Fourth, the Simple View helps me to quickly conceptualize and organize my classroom reading practices so they prevent reading difficulties from happening in the first place. To Understand Reading Difficulties, Graph the Simple View The Simple View of Reading describes the constant interaction between two dynamic processes: language comprehension and word recognition. Graphing the two processes makes this interaction even easier to see. To create a graph, first think of a child. Then think of how much difficulty or ease that child has with each process. This difficulty or ease can be represented as a specific point on each process line. For instance, a point on the far left end of the word recognition line would represent a student who is experiencing great difficulty in decoding. Meanwhile, a point somewhere towards the middle of the line shows a child who finds decoding to be only somewhat difficult (or somewhat easy), and a point on the far right denotes a student who has automatic and effortless word recognition.The same holds true for any child’s position on the language comprehension line. Next, show the Simple View’s two processes as two perpendicular intersecting lines. Viola! We now have a graph with quadrants of reading variability. We can use these four quadrants to frame our observations and assessments of any child’s reading behaviors. [iv][v] [vi] Any reader not in the “typical reader” quadrant can be said to have some type of regularly occurring reading difficulty.The figure below shows and defines categories of readers as described by their position in the quadrants. Of course, assessments helps us to pinpoint a reader on the graph. Information from reading words lists, running records, and oral reading fluency probes give information on word recognition. Assessments that measure vocabulary, metacognition skills, and background knowledge give us information on language comprehension. Plotting a reader as a point on the graph gives a student’s general reading profile or category[vii]. Plotting many students gives a scatter plot that generally describes the make up of a classroom or roster. Below are scatter plots from a hypothetical general education classroom (20 students) and a reading remediation roster (10 students). The second graph shows one student with hyperlexia, three students with dyslexia, two students who are having some difficulty with word recognition, and four students who have deficits (to varying degrees) in both word recognition and language comprehension. Keep in mind that reading comprehension is strong only when a reader has strength in both variables. Conversely, reading comprehension is always negatively affected by a weakness in either variable. Thus, even though a boy has a high degree of language comprehension, he could still show a low degree of reading comprehension. In this case, a lack of word recognition (decoding) keeps the child from accessing meaning. If you were to read this sentence to this boy – “A volcanic eruption was imminent” – he’d know just what it meant. But if you asked him to read it independently, he would struggle through the words volcanic, eruption, and imminent, and in the end, might have no idea of the sentence’s meaning. The End Goal In earlier blog’s, I’ve described the reading process in terms of the Eternal Triangle. This time it’s been The Simple View of Reading. When I think of how the two inform one another, my takeaway is this: successful and happy readers effortlessly recognize words as they read AND exist in a constant state of language comprehension and meaning-making. Conversely, unsuccessful readers have a limited ability to break the code, cannot effortlessly recognize words as they read, and/or lack the skills and knowledge that generate high amounts of language comprehension. So, as a teacher of reading, where do I put my instructional eggs? Into two baskets, of course: practices that help kids “break the code" and promote effortless word recognition, and practices that develop a child’s ability to make meaning and comprehend language while reading. Reading is a complex process. Many things can go wrong as teachers teach it and learners learn it. Still, reading difficulties can be prevented. One way to accomplish this goal is to employ general classroom instruction that offer all children many opportunities to learn and practice important skills while simultaneously supporting striving readers and writers. In upcoming blogs, I’ll share examples of this type of instruction. Sources

|

Mark WeaklandI am a teacher, literacy consultant, author, musician, nature lover, and life long learner.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed