|

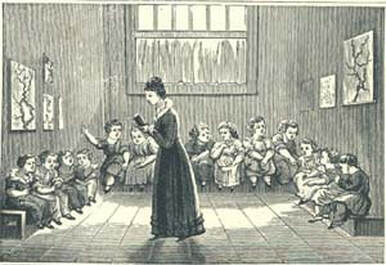

Women’s History Month is here, providing space to celebrate and reflect on the contributions of women over the years. In the area of reading instruction and research, women have consistently been at the vanguard of formulating reading theories, testing them through study and experimentation, and using them to build classrooms practices that teach children to read, write, and spell. As I think about women in history, I believe reading research is an area of science where women have consistently shone across the many decades. Reading Researchers Historically, women were not welcome in sciences such as physics, astronomy, chemistry, and medicine. Of course there were outliers – Marie Curie, Elizabeth Blackwell, Jane Goodall and Rachel Carson come to mind – but by and large, women were not encouraged to pursue or even allowed to enter scientific studies. But in the sciences of education and reading, this was not the case. When I think of those who have contributed to my understanding of what reading is and how I can best teach it, my thoughts quickly go to a list of women, including Elfreida Hiebert, Dolores Durkin, Dorothy Strickland, Margaret McKeown & Isabel Beck, Linda Gambrell, Catherine Snow, and Mary Anne Wolf. From thematic teaching and vocabulary instruction to reading comprehension and the neurobiology of the reading brain, the work of these researchers helped me to see that seemingly disparate parts of reading are actually facets of a complex and sparkling whole. Equally important, their insights have allowed many, including myself, to develop routines, activities, and curriculum that increasingly give all children a greater chance of becoming fluent readers, writers, and spellers. The list above doesn’t include my all-time Big Three of reading researchers. That trio would be Louise Rosenblatt (the transactional nature of reading), Jean Chall (stages of reading development), and Linnea Ehri (the essentiality of orthography), all of whom I’ve mentioned in previous blogs. If you don’t know these scientists, I encourage you to look them up, read about them, and reflect on what they’ve brought to the teaching of reading. Dorothy Strickland Maryanne Wolf Linnea Ehri A small sample of powerful reading scientists/researchers Women as Teachers As I reflect on reading researchers, I can’t help but wonder about the role of American women in education and how their progress in the field of teaching has ebbed and flowed over time. According to a pithy article in The Western Carolina Journalist, prior to 1850, teaching was a career dominated by men. But enormous social changes in the latter part of the 19th century brought about an almost complete reversal. As industrialization lured men into money-making businesses – building and running railroads, managing factories, trading in the stock market – thousands of teaching positions opened up. At the same time, immigration brought more children into cities, creating a demand for more teachers. Over the decades, women in education, who now comprise more than 80% of all teachers, made better wages, achieved status, and gained freedoms and opportunities to further their careers. They also suffered through large classroom sizes, meager pay, and burdensome oversight from male administrators. To this day, advancement continues to march forward and lurch back. Unions, as well as changing societal norms, have helped women achieve economic protections, better working conditions, more career education, and organizational positions such as curriculum directors, principals, superintendents, and senior researchers. But at the same time, some in the greater world still see teaching as “women’s work” – a belittling and ignorant phrase – and pay for women in all fields, including education, continues to lag behind that of men. An early teacher

Illustration via American Antiquarian. Those Who Can, Teach Finally, I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention my mother, an educator and lover of science. She was a huge influence on what I’ve learned about the teaching of reading and her career journey reflects both the joys of teaching and the struggles of women to be truly free and equal. As a young woman, she showed a keen intellect and a knack for observation of the natural world. She was interested in the sciences and in high school garnered a science scholarship to attend Temple University. But my grandfather, a school principal at the time, discouraged my mother’s love of science and desire for advanced study, instead strongly suggesting that she study nursing (the profession of my grandmother) or teaching. In the end, my mom choose teaching, attended a local Pennsylvania Teachers College, and had a long and satisfying career as a most excellent teacher, teaching as a reading specialist, a university professor, and a first grade teacher. Like many women, her accomplishments were astounding and included the raising of three children, running the family’s day-to-day operations, sometimes being the major bread winner, managing classrooms of rambunctious elementary-age boys and girls, and teaching the essential skill of reading to hundreds of children, thus changing their lives forever. So, here's to the women of the world, to the teachers and researchers, and to all those working to help people everywhere become more educated and open minded! Sources |

Mark WeaklandI am a teacher, literacy consultant, author, musician, nature lover, and life long learner.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed