|

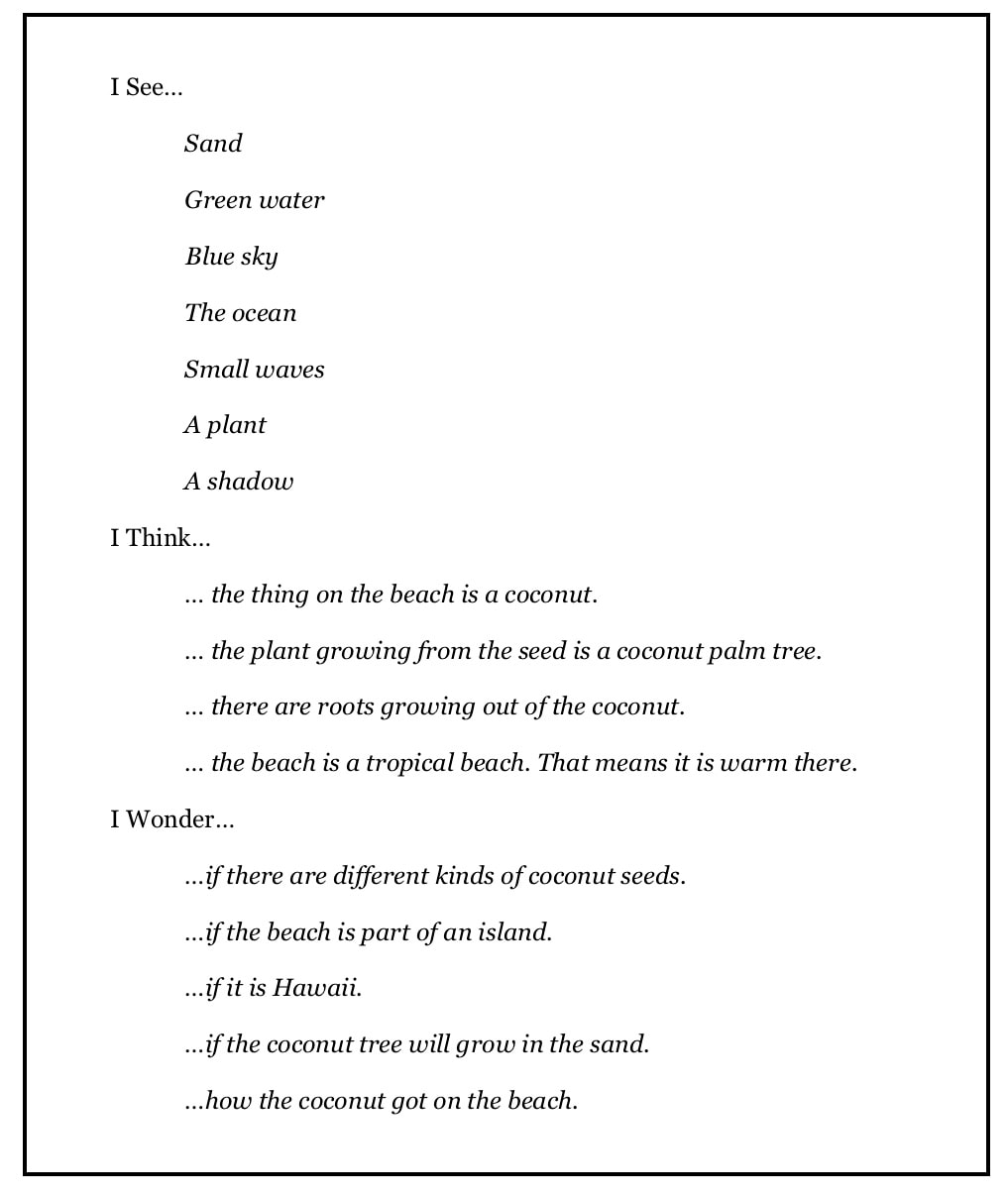

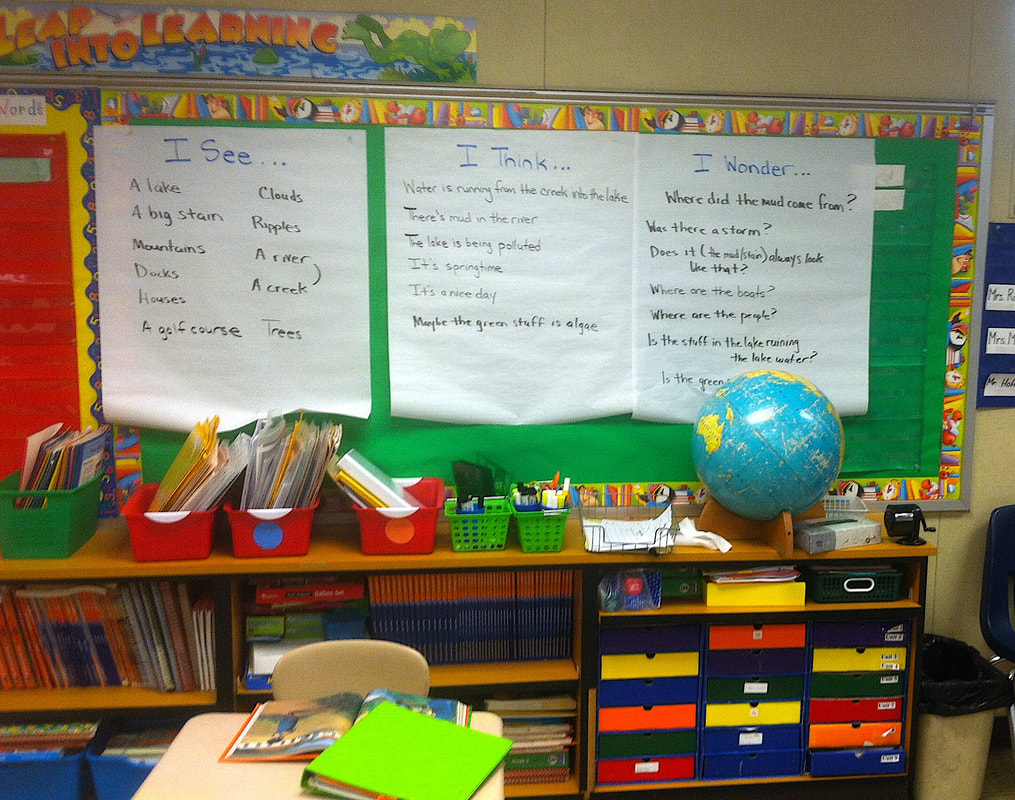

My last blog post promised more easy-to-do activities; this post gives another one. But first, a brief recap of what language comprehension is and why it is so important to skillful reading. Reading arises when both word recognition and language comprehension are well developed and richly interacting. Neither is more than another; both are made up of multiple components. For example, the components of language comprehension include background and topical knowledge, vocabulary knowledge, an understanding of grammar and syntax, a grasp of metacognition strategies, and the ability to regulate your focus and employ your strategies. All of these, as well as the components of word recognition, must be firmly if skillful reading is going to occur. SEE, THINK, WONDER. See, Think, Wonder comes from Harvard University’s Project Zero, which promotes visual thinking. I was introduced to it while working with the wonderful teachers of Nicholas County, West Virginia, where many of them enthusiastically endorsed the activity, saying it did wonders (pun intended) for building background knowledge, setting the stage for learning, and helping students develop the ability to ask and answer questions. For all students, but especially young children and English language learners. it is an activity that builds oral language. For older students, it functions as both an activity and a reader-used strategy. Set up. As with the Slide Show, you will need a strong sense of the background knowledge you want to build. It could be a science theme like seeds and plants, a reading genre like biography, or a story setting like Mrs. Wade’s bookstore in Destiny’s Gift. Unlike the Slide Show, you’ll only need one picture. It could be scanned from your text, copied from an internet source, or pulled from an existing Slide Show. Or keep it super simple by opening up a book and sharing a big, bright picture with students gathered at your feet. Regardless of how you present it, pick your picture carefully. You’ll want it to be closely aligned to your story or theme, detailed enough to produce lots of language through discussion and questioning, and not too far beyond what they know and understand (their general background knowledge). Modeling. To teach it, begin with a think aloud. Show the picture to your students and tell them what you see. Be as concrete as possible and use “I see…” statements. Next, move to “I think…” statements. Finally, model “I wonder…” statements. Here’s an image that could be used to kick off any first grade science unit on the structure of plants. It’s also appropriate for introducing a story like A Seed is Sleepy by Sylvia Long or Up in the Garden, Down in the Dirtby Kate Messner. And here’s an example of language a teacher might use when modeling a See-Think-Wonder based on the picture. Guided practice. Once you have modeled the strategy, move to guided practice with the whole group. Show an appropriate picture, give your students 10 seconds to notice things in the picture (like a detective looking carefully for clues), and then randomly call on individuals to tell you one thing they see. Don’t let them tell you everything they see, as some will try to do. Teach them to share one observed item at a time.

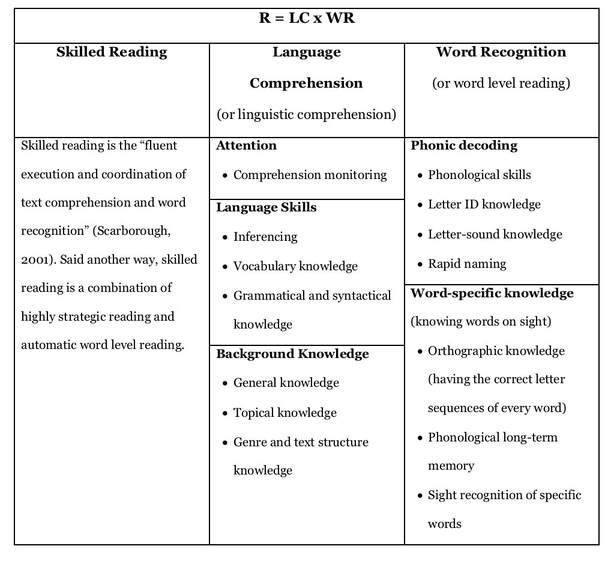

After you have modeled this strategy with the students and then guided them through it as a whole group, put them into groups of 2, 3, or 4 and have them try it for themselves. I’d suggest you just allow them to talk at first, rather than writing it down in three columns or completing some type of worksheet. Writing can come in later, when older students have a much firmer grip on using the strategy (see Figure 4.5). Also, writing everything down can be laborious for some students, while talking can be enjoyable, so why not give kids time to talk via an educational activity? Meander among the groups and listen to the talk, nudge into line any groups or individuals that are straying from the topic, and positively reinforce those groups and individuals who are exhibiting behaviors that are appropriate to the task. Later, spend a few minutes back in the whole group for a debriefing session. You can point out comments that were especially pertinent and provide praise for those who expended excellent effort. When to use it. See-Think-Wonder is both an activity and a strategy. As an activity, it builds language comprehension. Promoting “See-Think-Wonder” as something students do prior to independent reading turns it into a strategy that sets the stage for learning, activates prior knowledge, and generates questions that increase engagement. For example, this might take place in a guided reading group, when you hand out books, talk about the title, and then say, “Do a picture walk through this book and ask yourself, ‘What do I see, what do I think, what do I wonder?’” Likewise, explicitly show a whole group how to use it prior to reading science or social studies text. Say things like, “Good readers take the time to see, think, and wonder about the pictures, maps, and diagrams in the books they read. We are practicing this strategy so that you can use it independently. When you use this strategy, you become a reader who understands more." First, A Bit of Background Knowledge To become a skilled reader, a child must master sound-letter combinations, combine letters into phonic “chunks,” automatically recognize words, link words to specific meanings, make connections between text ideas, understand genre, integrate background and topical knowledge, employ strategies to stay on task, and much more. In previous blog posts, I’ve tried to describe and explain how this complexity interacts in a process that ultimately gives rise to skillful reading, and I’ve used two reading models to do so: the Eternal Triangle and the Simple View of Reading. The Simple View of Reading, expressed as a formula, R = WR x LC, tells us skilled reading arises when both word recognition (WR) and language comprehension (LC) are well developed and richly interacting. It’s important to note the formula does not emphasize one variable more than another; the focus of this blog, language comprehension, is just as important to skillful reading as word recognition (or decoding) is, and this means teachers of reading must know how to 1) build it in all students, 2) assess how much of it students possess, and 3) differentially target and teach students who lack any of its specific elements. Each of the Simple View’s variables – decoding and language comprehension - are made up of multiple components. Compiled from the writings of Hollis Scarborough and David Kilpatrick, the chart below provides a summary of many of them. Ironically, the Simple View of Reading is not simple! Nonetheless, Scarborough and Kilpatrick can help us in our quest to understand what we must teach if students are to learn how to read and avoid reading difficulties. A Simple But Effective Activity Now that we have some background knowledge on language comprehension, let’s dive into the nuts and bolts of how we might strengthen it in students, be they first, fourth, or even ninth graders. I have three language comprehension activities to share and I’ve chosen them because in COVID times, they can be done either in a classroom or online. Also, all are relatively easy to do (once you learn their routines) and in sum they present multiple components of the language comprehension variable. This post describes and explains the Slide Show. In upcoming weeks, I’ll give See-Think-Wonder and the Interactive Read Aloud. The Slide Show We all know the power of YouTube videos. In a matter of minutes, one clip can convey a lot of information. But my favorite activity for quickly communicating background and topical knowledge, as well as building vocabulary, is a modern-day slide show. In the ancient days of my youth, slide shows were all about hardware. There were real slides (translucent film fitted inside a frame), a hard plastic carousel that stored them, and a slide projector that beamed light through the slides and onto a screen. Today’s slide shows, however, are software-based, made from digital images culled from the internet and pasted into a slideshow app. Unlike video clips, slide shows have no animation or narration, meaning you can create space for contemplation, letting students ponder a particular slide, asking questions about it, and soliciting comments. Set Up. To create a slide show, you need an app like PowerPoint or Keynote, one that has a slide show function. You also need a strong sense of the concept or content you want to teach. Examples include the idea of erosion, a reading genre like fairy-tales, or a specific story setting, like a farm in Wyoming (Stone Fox), the summer of 1968 in Oakland, California (One Crazy Summer), or the woods on a cold, winter night under a full moon (Owl Moon). After you have decided what to teach, do a Google Image query and start sifting through pictures. Choose engaging ones that also tie into the words and concepts you will touch upon in your upcoming story, theme, or unit. The trick is to pick information-rich photographs that both pique the interest of kids and provide talking points for vocabulary and background knowledge. Next, import the pictures into your slide show app and make some brief notes (mental or written) about the information you want to impart as you show each picture. Now you’re ready to go. Modeling. It’s always a good idea to model the behaviors you want your students to exhibit, so first model how to notice things on each slide. Using direct and explicit language, explain to the children what they are seeing in each picture and give definitions for vocabulary words, like this one, which goes with a slide in the figure below. “This boy is wearing a kimono. A Japanese kimono is a traditional kind of clothing. In Japan, people wear kimonos for special occasions.” Build in appropriately sophisticated language whenever possible and intersperse the noticing with questions. “What do you notice in this picture?” and “What do you think this picture is showing?” The slide show above could be used to build knowledge prior to reading books that reference Japan, such as Wabi Sabi by Mark Reibstein or Grandfather’s Journey and Kamishibai Man by Japanese-American author and illustrator Allen Say. Under each photo, I’ve included examples of what I might say to students as I show each slide. These comments are not part of the slides and I don’t show text to students. No matter the content, the overarching goal is to orally build language comprehension through showing pictures and giving information verbally.

Slide shows can be as long or as short as you want them to be. However, if you make them too short, they won’t give enough information, and if you make them too long, you’ll eat up too much time and your students may lose interest. Keep in mind the age and attention span of the children you teach. A show of twelve to twenty photos is a length to aim for, and total time for the activity is less than 15 minutes. When to use. I recommend showing a slide show prior to reading a historical novel or any book with a setting unfamiliar to many students. Earlier I mentioned Stone Fox, a chapter book about a sled dog race. Before my 3rd grade guided reading group began this book, I showed them a slide show that included pictures of racing sleds, sled dogs, mushers, homestead farms, a map of Wyoming, and various types of people you might see in Wyoming, both current and historical. Although the students and I could have talked all morning about the pictures (the kids were into them, especially the ones featuring dogs), I set a time limit of 15-minutes because it was also important to start reading. It can be tricky to find the right balance between too little and too much discussion but with practice, you’ll figure out what works best. The ultimate goal of a slide show is to build a child’s language comprehension by adding background, topical, and vocabulary knowledge to a child’s mental lexicon. Then, when it comes time to read, this knowledge is available to the reader. If a picture is worth a thousand words, then a slide show with a dozen or more pictures really adds up! Sources and Citations

|

Mark WeaklandI am a teacher, literacy consultant, author, musician, nature lover, and life long learner.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed