|

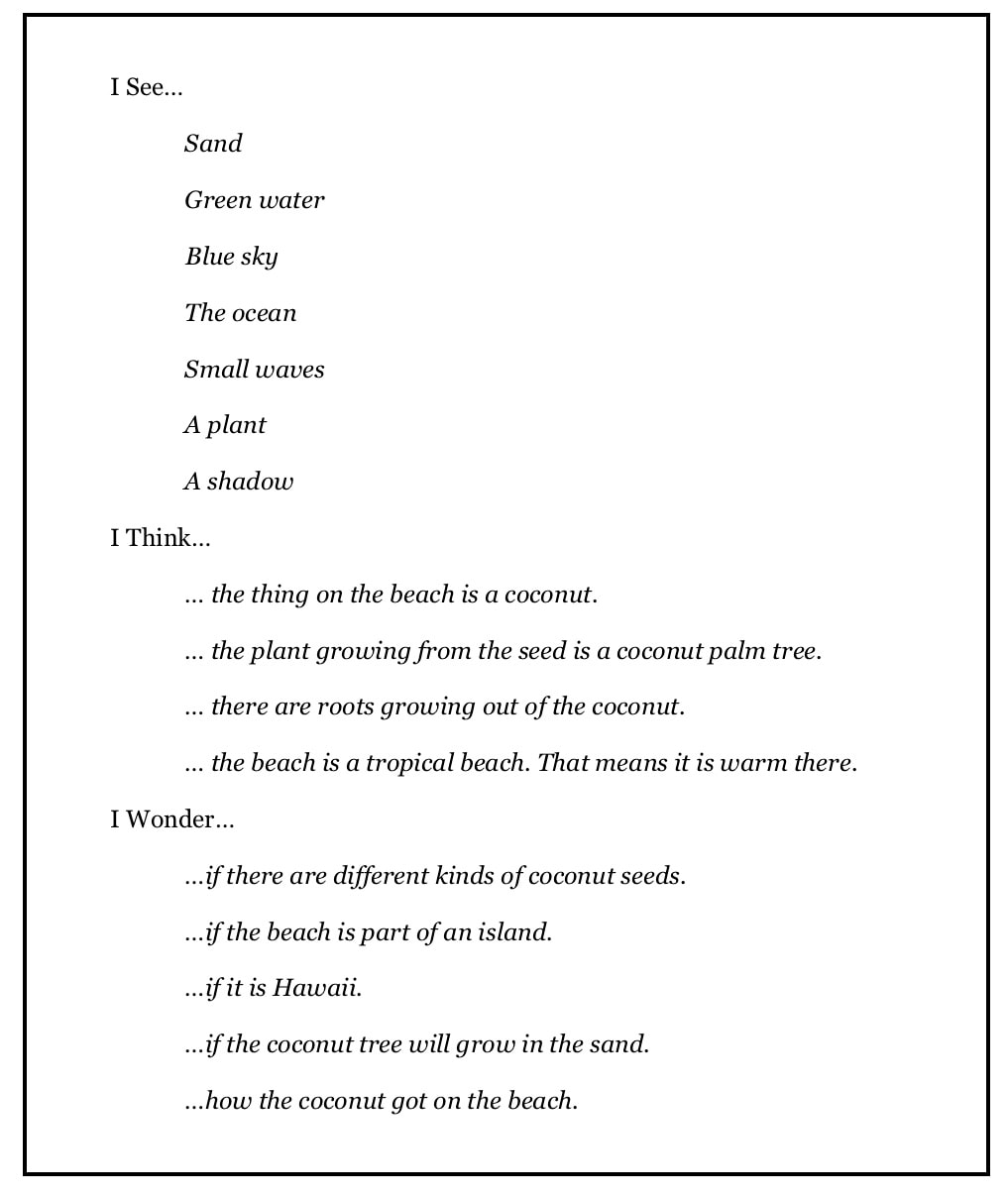

My last blog post promised more easy-to-do activities; this post gives another one. But first, a brief recap of what language comprehension is and why it is so important to skillful reading. Reading arises when both word recognition and language comprehension are well developed and richly interacting. Neither is more than another; both are made up of multiple components. For example, the components of language comprehension include background and topical knowledge, vocabulary knowledge, an understanding of grammar and syntax, a grasp of metacognition strategies, and the ability to regulate your focus and employ your strategies. All of these, as well as the components of word recognition, must be firmly if skillful reading is going to occur. SEE, THINK, WONDER. See, Think, Wonder comes from Harvard University’s Project Zero, which promotes visual thinking. I was introduced to it while working with the wonderful teachers of Nicholas County, West Virginia, where many of them enthusiastically endorsed the activity, saying it did wonders (pun intended) for building background knowledge, setting the stage for learning, and helping students develop the ability to ask and answer questions. For all students, but especially young children and English language learners. it is an activity that builds oral language. For older students, it functions as both an activity and a reader-used strategy. Set up. As with the Slide Show, you will need a strong sense of the background knowledge you want to build. It could be a science theme like seeds and plants, a reading genre like biography, or a story setting like Mrs. Wade’s bookstore in Destiny’s Gift. Unlike the Slide Show, you’ll only need one picture. It could be scanned from your text, copied from an internet source, or pulled from an existing Slide Show. Or keep it super simple by opening up a book and sharing a big, bright picture with students gathered at your feet. Regardless of how you present it, pick your picture carefully. You’ll want it to be closely aligned to your story or theme, detailed enough to produce lots of language through discussion and questioning, and not too far beyond what they know and understand (their general background knowledge). Modeling. To teach it, begin with a think aloud. Show the picture to your students and tell them what you see. Be as concrete as possible and use “I see…” statements. Next, move to “I think…” statements. Finally, model “I wonder…” statements. Here’s an image that could be used to kick off any first grade science unit on the structure of plants. It’s also appropriate for introducing a story like A Seed is Sleepy by Sylvia Long or Up in the Garden, Down in the Dirtby Kate Messner. And here’s an example of language a teacher might use when modeling a See-Think-Wonder based on the picture. Guided practice. Once you have modeled the strategy, move to guided practice with the whole group. Show an appropriate picture, give your students 10 seconds to notice things in the picture (like a detective looking carefully for clues), and then randomly call on individuals to tell you one thing they see. Don’t let them tell you everything they see, as some will try to do. Teach them to share one observed item at a time.

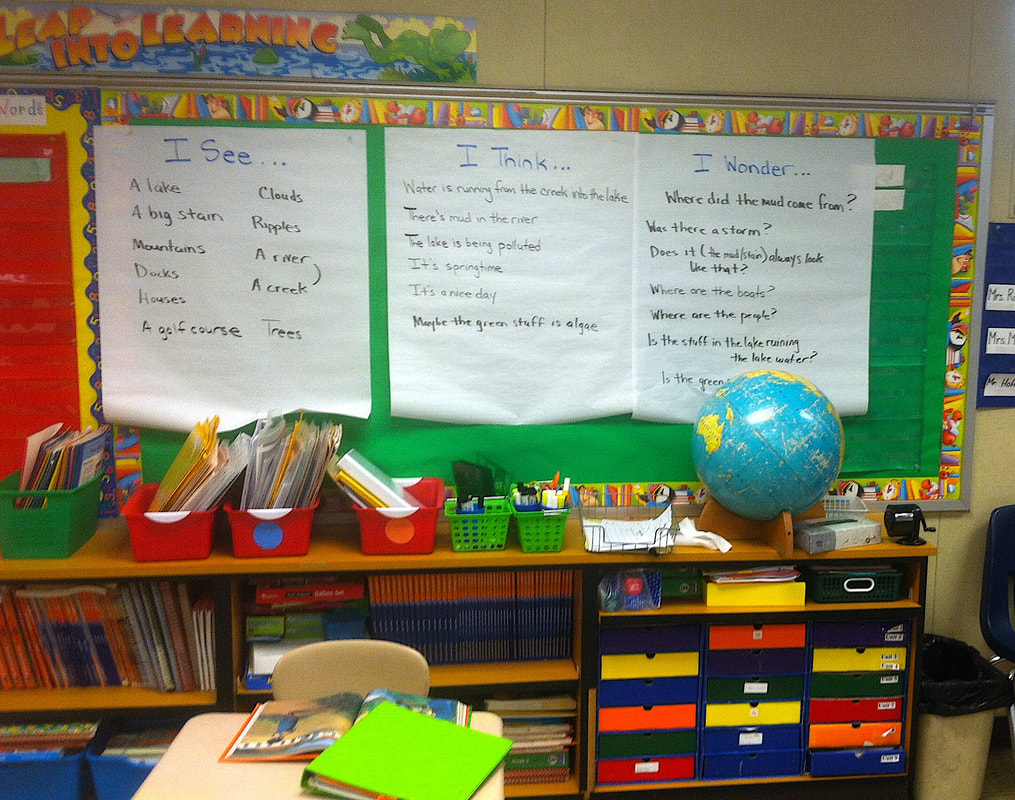

After you have modeled this strategy with the students and then guided them through it as a whole group, put them into groups of 2, 3, or 4 and have them try it for themselves. I’d suggest you just allow them to talk at first, rather than writing it down in three columns or completing some type of worksheet. Writing can come in later, when older students have a much firmer grip on using the strategy (see Figure 4.5). Also, writing everything down can be laborious for some students, while talking can be enjoyable, so why not give kids time to talk via an educational activity? Meander among the groups and listen to the talk, nudge into line any groups or individuals that are straying from the topic, and positively reinforce those groups and individuals who are exhibiting behaviors that are appropriate to the task. Later, spend a few minutes back in the whole group for a debriefing session. You can point out comments that were especially pertinent and provide praise for those who expended excellent effort. When to use it. See-Think-Wonder is both an activity and a strategy. As an activity, it builds language comprehension. Promoting “See-Think-Wonder” as something students do prior to independent reading turns it into a strategy that sets the stage for learning, activates prior knowledge, and generates questions that increase engagement. For example, this might take place in a guided reading group, when you hand out books, talk about the title, and then say, “Do a picture walk through this book and ask yourself, ‘What do I see, what do I think, what do I wonder?’” Likewise, explicitly show a whole group how to use it prior to reading science or social studies text. Say things like, “Good readers take the time to see, think, and wonder about the pictures, maps, and diagrams in the books they read. We are practicing this strategy so that you can use it independently. When you use this strategy, you become a reader who understands more." Comments are closed.

|

Mark WeaklandI am a teacher, literacy consultant, author, musician, nature lover, and life long learner.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed