|

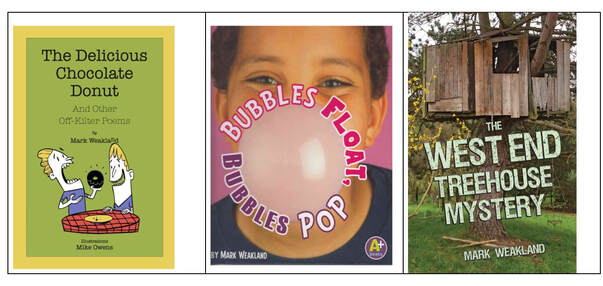

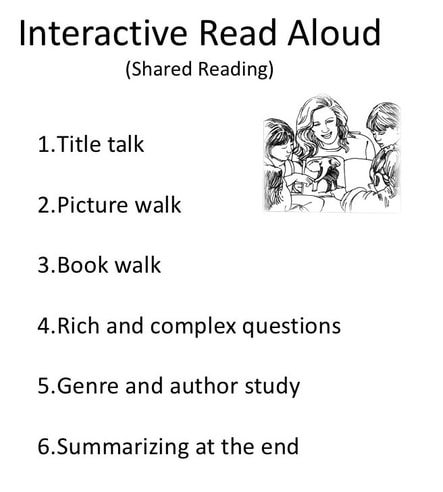

According to Kilpatrick (2015) and Scarborough (2001), metacognition, background knowledge, and topical knowledge are components of language comprehension, one of the two variables that describe the Simple View of Reading (the other being word recognition). Other components of this important variable include vocabulary knowledge, grammatical and syntactical knowledge, and self-monitoring. The more a student has of each, the more chance he has of understanding what he has read. Additionally, when the many parts of language comprehension are strong, reading difficulties are less likely to occur. Conversely, if the parts are weak, reading difficulties are more likely to occur. Making meaning is foundational to what it means to read; one’s ability to construct meaning from written text is dependent on knowledge. When language knowledge is combined with the automatic recognition of correctly spelled words, the brain’s reading circuits are connected and the reading process can unfold. In a 2018 overview of the reading process, researchers Anne Castles, Kathleen Rastle, and Kate Nation said this: “When children begin to learn to read, they usually already have relatively sophisticated spoken-language skills, including knowledge of the meaning of many spoken words.” We know, however, that due to differences within families, languages, and social and economic environments, some children come to school with deficits in spoken word (language) knowledge. So, to head off reading difficulties caused by a lack of language comprehension, we have to build language comprehension knowledge of all types, especially background knowledge. It’s well known that background knowledge is essential for reading comprehension (Coppola, S. 2014; O’Reilly, T., Wang, Z., & Sabatini, J., 2019). Just think about it: to construct a mental model of what you are reading, it helps to know something about the text topic. The knowledge can consist of specific information, general information, or both. Regardless, the more a reader knows about any topic, the easier it is for him to read a text, understand it, and retain its information (Neuman, Kaefer, & Pinkham, 2014). Thus, a teacher will find it easier to digest the concepts presented in this blog than a fighter pilot or financial advisor. Interactive read aloud Reading to children is a simple pleasure. When infused with thought-provoking questions and purposefully modeled reading strategies, reading aloud becomes an effective and practical way to build language comprehension. More specifically, interactive read alouds can build background knowledge, topical knowledge, vocabulary knowledge, genre knowledge, and the ability to use metacognition strategies (such as predicting or visualizing). In any give classroom there is a wide range of reading achievement. Thus, reading out loud gives some students a way to access and discuss a book written well above their independent reading level. For other students, a read aloud piques interest in a book they can read independently at a later time, once it is placed on a book-shelf or in a browsing bin. Finally, an interactive read aloud not only generally strengthens components of reading comprehension, but it also provides explicit opportunities to model specific reading skills, such as fluent reading, re-reading, and defining vocabulary from context. It all begins with a carefully chosen quality children’s book, one that is engaging, of any genre, and full of rich vocabulary and concepts. You’ll also need a strong sense of what language comprehension components you want to focus on and an understanding of how to teach them. Let’s tackle this last element first. A series of purposeful activities makes up a typical interactive read aloud. They can include any or all of the following, done for a variety of purposes: Title talk, picture walk, and/or book walk.

Rich and complex practices like an Interactive Read Aloud demand rich and complex study, more than what this blog can provide. Perhaps you’ll want to check out these resource books and material, as they might help you take your instruction to a higher level.

SOURCES

|

Mark WeaklandI am a teacher, literacy consultant, author, musician, nature lover, and life long learner.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed