|

My August and September 2016 blogs were devoted to the idea of teaching children strategies for spelling unknown words. Specifically I discussed spelling by analogy (using a word that you know as template for spelling a word you don’t know) and spelling by sound (hear the sounds, assign letters and patterns that make those sounds). Today's offering is See the Word Inside Your Head, the strategy accomplished spellers use most often.

Some children develop the ability to “see a word inside their head” naturally. Others do not. To encourage students to build and use a repository of stored words in their brains, teach them to study spelling words using the steps given below. Then, when it comes time to spell words independently during writing (or on a test), remind students to use these steps: see the word in your mind, write the word, and check the word. As teachers, we hope that by intentionally using “see-write-check,” students will later generalize the strategy into the automatic ability to visualize a word, write it down, and then check it against the word stored in their brain dictionary. I have seen variations of the “see the word” strategy in core-reading programs for a couple of decades now. My most recent encounter with it was while perusing the stand-along spelling program Spelling Connections, published by Zaner-Bloser. Spelling Connections presents a three-step strategy for studying spelling words. Here is my two-step variation. 1. Say-See, Hide-See

Here is an example of how I might model my use of this strategy and use a think aloud to explain its workings:

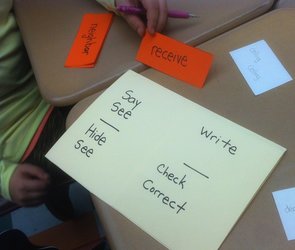

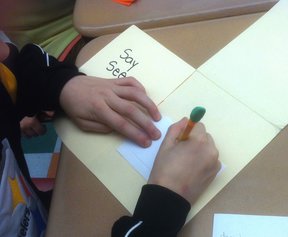

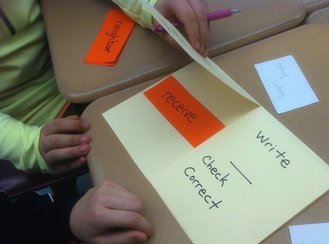

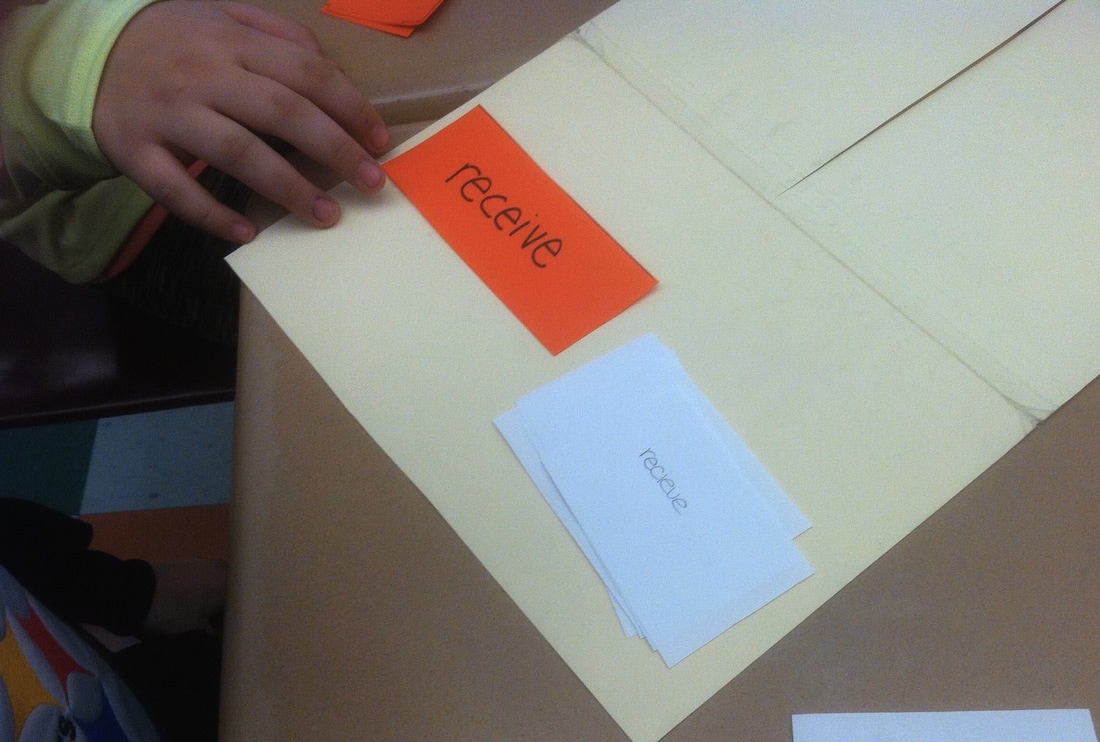

An easily constructed “flip folder” provides opportunities for students to practice the strategy “see the word in your head.” The activity, which can be done independently or with a buddy, is designed for instant error correction. A student spells a word and then checks it for correctness. If the word is misspelled, the student corrects it before moving on to the next word. To make a flip folder, you need a manila folder, a marker, a set of word cards, and stack of blank slips of paper. The activity’s routine mirrors the two-step word study strategy outlined above. Here is a brief description of the routine, which is also presented in the pictures below.

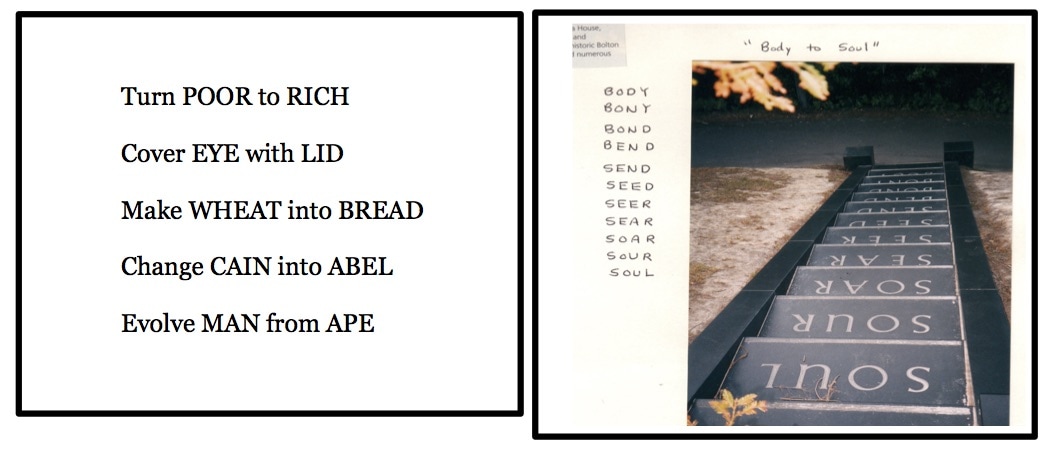

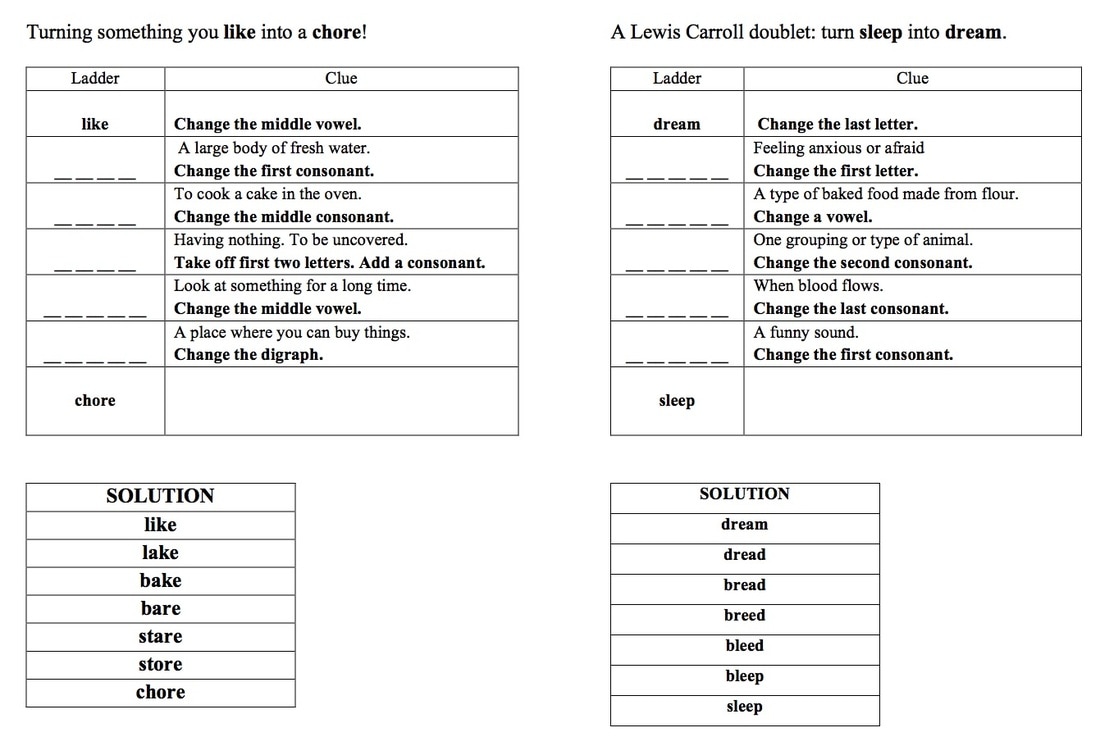

Word ladders (also known as word-links, laddergrams, and doublets) involve morphing one word into another by changing one letter, or set of letters, at a time. Each change creates a new word, and each new word is a rung on the ladder. Starting with the word at the bottom of the ladder, it may take a speller five, six, or seven or more words to reach the target at the top. In this way, a HEN is changed into a FOX: hen, pen, pin, fin, fix, fox! I first heard of word ladders, and began using them, while teaching in 3rd grade classrooms. Later I learned Tim Rasinski made them popular with his Daily Word Ladders books for teachers (Rasinski, 2012; 2008). But while researching my upcoming Stenhouse book, Super Spellers, I discovered Lewis Carroll was the one who invented them! Carroll, best known as the author of Alice in Wonderland, was also an eminent mathematician and a renowned puzzle creator. In 1877 he created a word puzzle that he dubbed the doublet, a name likely inspired by the witches’ incantation in MacBeth: “Double, double, toil and trouble.” Vanity Fair published Carroll’s doublets in 1879 and they quickly became all the rage. Below are five of his doublets (can you solve them?). Also shown is a word ladder that is actually climbable! While visiting a botanical garden in New Zealand, my wife, Beth, and I climbed these etched granite steps, took a picture from the top, and wrote down the solution to the doublet BODY and SOUL in our scrapbook. Word ladders help children notice sounds, especially inner vowels. To change one word into another, students must listen to sounds and decide on letters. Unlike Carroll, who gave puzzlers no clues regarding the ladder rungs, you can explicitly tell your students what each word on a rung is. Over time, as young children and struggling readers write each word in the ladder, they notice patterns within words and between words. If desired, you can also discuss the meaning of the words that make up a ladder. In this way, SPELLING becomes VOCABULARY! There are plenty of word ladder activities available for purchase from Tim Rasinski and others. Below you can see one of Carroll’s classic doublets (with its solution), plus one I dreamed up: turn a CHORE into something you LIKE. But you can create these word sequences yourself. While I like to create ladders in the spirit of Carroll’s doublets, the words on either end don’t have to be tied together by a common theme. Also, once students become accomplished at completing word ladders, you can put them to work making their own. It’s a real accomplishment when a child authors a word ladder that becomes part of a literacy center. I have used word ladder activities with large groups of kids, but I also have guided children through them in small groups during guided reading time, where I used a word ladder as a word study activity. Once children can competently recreate the routine on their own, they can complete word ladders with a buddy during independent work time.

I suggest you have students write their word ladder sequences on paper. A whiteboard or iPad will work but the written words need to be relatively small. Paper is probably best if your ladder is longer than five or six words. Students should never erase the previous word. The point is to create a sequence that students can look through to see the relationships between the words. Let’s say you created a word ladder that changes hen into fox through the sequence I outlined in the first paragraph. To teach this word ladder, start with the word hen. Say the word and have the kids repeat it back to you. You may even want to have the students stretch that word and zap it so they can hear the sounds in the word. I think highlighting inner vowel sounds is especially important because I’ve found that these are the sounds hardest for students to hear, reproduce, and associate with correct letter combinations. After students have written their starting word, you write the word and have your students check their spelling against yours. Next, follow this little routine:

Here is an example of what a teacher might say during a word ladder designed to focus on pattern and meaning, rather than just individual sounds and letters. The words come from one of my ladders: make a CHICK CHEEP (the solution is chick, chin, chip, lip, leap, cheap, cheep). After a teacher briefly reviews the ee and ea vowel teams, and after she leads the class through the first four words (chick, chin, chip, lip), her instruction might sound like the following:

Once you start moving into this type of word ladder, Patricia Cunningham’s Making Words books become a wonderful resource. There are probably a dozen or more of these books on the market, and they address many grade levels. While not exactly word ladders, each lesson follows the basic process of swapping sounds and letters in and out of words to make new words. Each Making Words lesson draws on the letters of a relatively long target word, such as oatmeal, to create sets of smaller words that follow patterns, such as eat, meat, team, meal, ate, mate, late, and so on. Word ladders and making word activities are not only opportunities for children to hear sounds, assign letters, notice patterns, and think about meaning. They are also opportunities for you to conduct formative assessment. As you walk among the working students, notice who is confused about patterns or sounds and who is not. Explore their thinking process by saying, “Tell me why you put this letter here” and asking, “What pattern are you thinking about right now?” Carry a clipboard and piece of paper with you and you can take note of the children who require re-teaching, as well as list the areas in which they need additional instruction

|

Mark WeaklandI am a teacher, literacy consultant, author, musician, nature lover, and life long learner.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed