|

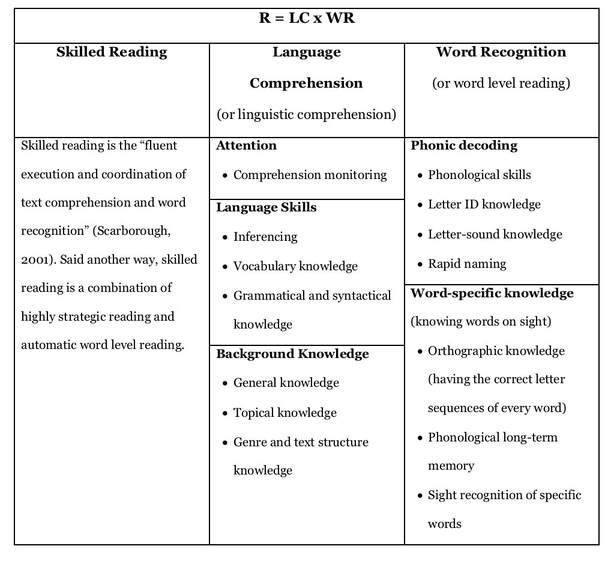

First, A Bit of Background Knowledge To become a skilled reader, a child must master sound-letter combinations, combine letters into phonic “chunks,” automatically recognize words, link words to specific meanings, make connections between text ideas, understand genre, integrate background and topical knowledge, employ strategies to stay on task, and much more. In previous blog posts, I’ve tried to describe and explain how this complexity interacts in a process that ultimately gives rise to skillful reading, and I’ve used two reading models to do so: the Eternal Triangle and the Simple View of Reading. The Simple View of Reading, expressed as a formula, R = WR x LC, tells us skilled reading arises when both word recognition (WR) and language comprehension (LC) are well developed and richly interacting. It’s important to note the formula does not emphasize one variable more than another; the focus of this blog, language comprehension, is just as important to skillful reading as word recognition (or decoding) is, and this means teachers of reading must know how to 1) build it in all students, 2) assess how much of it students possess, and 3) differentially target and teach students who lack any of its specific elements. Each of the Simple View’s variables – decoding and language comprehension - are made up of multiple components. Compiled from the writings of Hollis Scarborough and David Kilpatrick, the chart below provides a summary of many of them. Ironically, the Simple View of Reading is not simple! Nonetheless, Scarborough and Kilpatrick can help us in our quest to understand what we must teach if students are to learn how to read and avoid reading difficulties. A Simple But Effective Activity Now that we have some background knowledge on language comprehension, let’s dive into the nuts and bolts of how we might strengthen it in students, be they first, fourth, or even ninth graders. I have three language comprehension activities to share and I’ve chosen them because in COVID times, they can be done either in a classroom or online. Also, all are relatively easy to do (once you learn their routines) and in sum they present multiple components of the language comprehension variable. This post describes and explains the Slide Show. In upcoming weeks, I’ll give See-Think-Wonder and the Interactive Read Aloud. The Slide Show We all know the power of YouTube videos. In a matter of minutes, one clip can convey a lot of information. But my favorite activity for quickly communicating background and topical knowledge, as well as building vocabulary, is a modern-day slide show. In the ancient days of my youth, slide shows were all about hardware. There were real slides (translucent film fitted inside a frame), a hard plastic carousel that stored them, and a slide projector that beamed light through the slides and onto a screen. Today’s slide shows, however, are software-based, made from digital images culled from the internet and pasted into a slideshow app. Unlike video clips, slide shows have no animation or narration, meaning you can create space for contemplation, letting students ponder a particular slide, asking questions about it, and soliciting comments. Set Up. To create a slide show, you need an app like PowerPoint or Keynote, one that has a slide show function. You also need a strong sense of the concept or content you want to teach. Examples include the idea of erosion, a reading genre like fairy-tales, or a specific story setting, like a farm in Wyoming (Stone Fox), the summer of 1968 in Oakland, California (One Crazy Summer), or the woods on a cold, winter night under a full moon (Owl Moon). After you have decided what to teach, do a Google Image query and start sifting through pictures. Choose engaging ones that also tie into the words and concepts you will touch upon in your upcoming story, theme, or unit. The trick is to pick information-rich photographs that both pique the interest of kids and provide talking points for vocabulary and background knowledge. Next, import the pictures into your slide show app and make some brief notes (mental or written) about the information you want to impart as you show each picture. Now you’re ready to go. Modeling. It’s always a good idea to model the behaviors you want your students to exhibit, so first model how to notice things on each slide. Using direct and explicit language, explain to the children what they are seeing in each picture and give definitions for vocabulary words, like this one, which goes with a slide in the figure below. “This boy is wearing a kimono. A Japanese kimono is a traditional kind of clothing. In Japan, people wear kimonos for special occasions.” Build in appropriately sophisticated language whenever possible and intersperse the noticing with questions. “What do you notice in this picture?” and “What do you think this picture is showing?” The slide show above could be used to build knowledge prior to reading books that reference Japan, such as Wabi Sabi by Mark Reibstein or Grandfather’s Journey and Kamishibai Man by Japanese-American author and illustrator Allen Say. Under each photo, I’ve included examples of what I might say to students as I show each slide. These comments are not part of the slides and I don’t show text to students. No matter the content, the overarching goal is to orally build language comprehension through showing pictures and giving information verbally.

Slide shows can be as long or as short as you want them to be. However, if you make them too short, they won’t give enough information, and if you make them too long, you’ll eat up too much time and your students may lose interest. Keep in mind the age and attention span of the children you teach. A show of twelve to twenty photos is a length to aim for, and total time for the activity is less than 15 minutes. When to use. I recommend showing a slide show prior to reading a historical novel or any book with a setting unfamiliar to many students. Earlier I mentioned Stone Fox, a chapter book about a sled dog race. Before my 3rd grade guided reading group began this book, I showed them a slide show that included pictures of racing sleds, sled dogs, mushers, homestead farms, a map of Wyoming, and various types of people you might see in Wyoming, both current and historical. Although the students and I could have talked all morning about the pictures (the kids were into them, especially the ones featuring dogs), I set a time limit of 15-minutes because it was also important to start reading. It can be tricky to find the right balance between too little and too much discussion but with practice, you’ll figure out what works best. The ultimate goal of a slide show is to build a child’s language comprehension by adding background, topical, and vocabulary knowledge to a child’s mental lexicon. Then, when it comes time to read, this knowledge is available to the reader. If a picture is worth a thousand words, then a slide show with a dozen or more pictures really adds up! Sources and Citations

Comments are closed.

|

Mark WeaklandI am a teacher, literacy consultant, author, musician, nature lover, and life long learner.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed