|

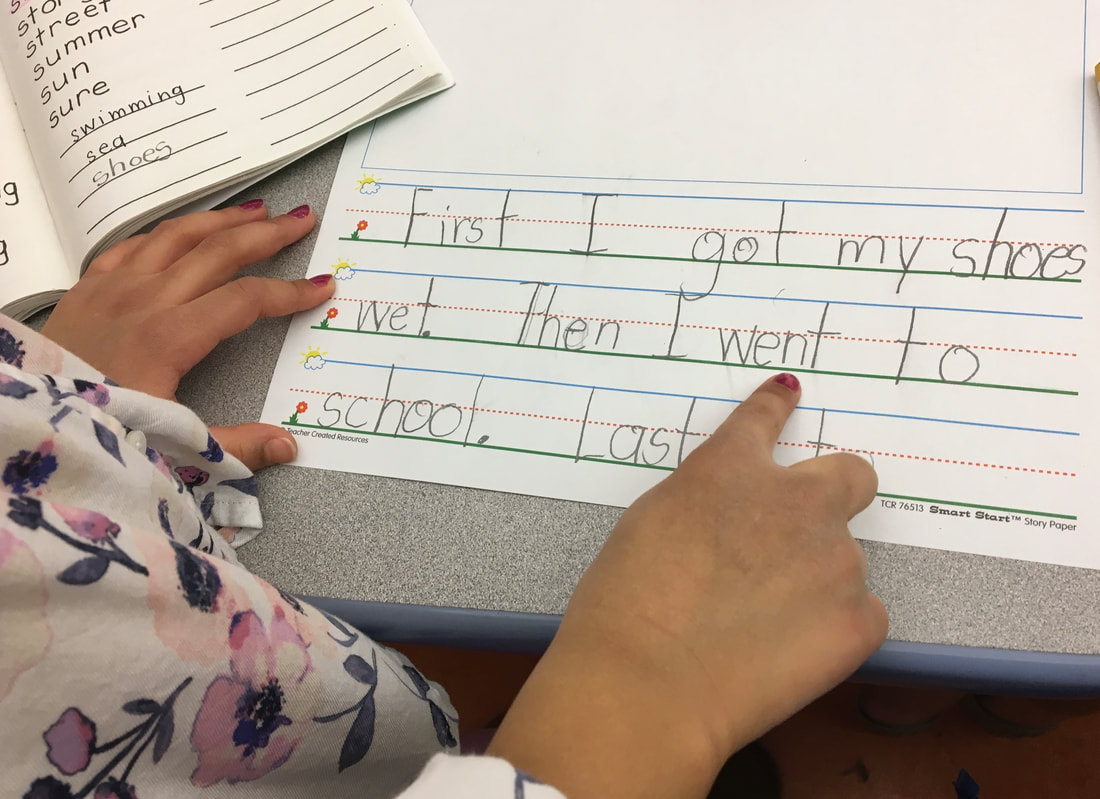

A masterful teacher friend recently told me she is working with a team of teachers to make their district's already strong kindergarten literacy program even stronger. She asked me to weigh in on two questions the team was grappling with, questions that concerned the use of sight words for writing and the pace of introducing letters. An edited version of our question and answer conversation is below. Using Writing Words in Kindergarten First, a bit of background. Kid Writing, the creation of Isabell Cardonick, Eileen Feldgus, and Richard Gentry, is an early literacy program that integrates phonology, spelling, phonics, reading and writing. I think it’s brilliant. Others think so, too, and I know a number of teachers who have used it for the bulk of their literacy instruction. Kindergarten Kid Writing in action The program provides many student-centered tools, including Writing Words (often called Crown Words). These words - for example my, are, is, am, and said – are frequently used by young writers when they write on topics of their choosing. To help children store these difficult to decode words in their brain dictionary, each sight word is paired with an engaging, rhyming picture. Examples are shown below. After a word is taught, a teachers posts the word on the wall where young writers can easily find it and then use it when writing. Writing Words in a classroom QUESTION “Do we keep our Kid Writing Words or get rid of them? We weren't sure if they went along with recent brain research / Science of Reading.” ANSWER I say keep the Kid Writing Words (Crown Words) and feel good about it! Here’s why. As we know from research, kindergarten spelling-writing-reading is developmental. We’ve known this for many years now, well before the term “science of reading” was bandied about. For kindergarten students, most word spellings are of a temporary nature. A kindergartener’s incorrect spellings, most often guided solely by sounds, are of a temporary nature and will eventually be replaced by correct spellings, which are made perfect and permanent through repetition and practice. Kindergarten teachers don’t need to worry that sound-spelling patterns don’t match, for example that the /ar/ sound spelling in ARE doesn’t match the /ar/ sound spelling in STAR. I’d say that kindergarten word spellings typically occur at the sound-letter level rather than at the sound-pattern level. Finally, two other reason you can feel good about keeping your writing words is that 1) the words foster independence (instead of asking a teacher how to spell a word like said, a child goes to the wall, finds the writing word, and spells it from there), and 2) the associations children make between the fun pictures and “tricky” words really help them remember the spellings. It’s the power of mnemonics! If you want to fine tune your Writing Words to be more closely connected to patterns, you could replace one or two of the rhyming non-pattern words with rhyming pattern words. The PIE of MY comes to mind. How about swapping that out for the SKY of MY (showing the word MY floating in a blue field with puffy white clouds)? Or instead of the CLAY of THEY or the HAY of THEY, use The HEY of THEY (show someone shouting instead of a haystack). Here’s another thought: While it is true that a few words - like OF, SAID, and WAS – have no analogous sound-pattern words, many sight words are pattern-based, can be presented with any number of analogous words, and will, at some point in a teaching sequence, become fully decodable. So don’t be afraid to show other pattern words when you teach these types of “sight words.” For example, later in the year when you review the Sky of My, show the words by, fly, and cry. Here the expectation is not mastery and permanent mapping but simple exposure. This practice goes hand in hand with your team’s move to group, present, and teach sight words that follow patterns (for example, me, we, he, be, she). I’m a big fan of this type of teaching because the human brain is a pattern recognition machine and so it makes sense to harness pattern recognition when teaching sight words. Grouping writing words - check out "The Keys of E" Introducing and Teaching Letters and Sounds

Again, before getting to the Q & A, a bit of background is called for. For the last eight or nine years, I have known kindergarten teachers who begin their school year with an Alphabet Boot Camp, a program for introducing all letters of the alphabet one letter per day. While I can’t speak to the general efficacy of the ABC Bootcamp program (look it up on the Kindergarten Smorgasboard website), I can speak to research that provides strong evidence that a letter-a-week pace is much too slow and a routine that teaches a letter-a-day is much more effective (see Jones & Reutzel, 2012, and Mcay & Teale, 2015, among others). In addition, there is long-standing research that shows the sequence in which you introduce letters can influence how easily and thoroughly letters and their associated sounds are learned. QUESTION Is the "Boot Camp" necessary? And how many letters per week should we teach? We are leaning towards just starting with teaching 2 letters each week (and possibly 3 as they are getting the hang of letters) with the goal of mastering letter names and sounds by around January. Also, we are looking at how the letters are taught in our Journeys curriculum. In the first 5 weeks of Journeys they do a letter each day - kind of like a letter "Boot Camp" - and then switch to one letter each week. It then takes all year to go through all the letters.” ANSWER If I was teaching kindergarten, I’d do the Boot Camp and then use the brisk pace of teaching you mentioned. Let's say you did the Boot Camp in October and then taught all the letters at a pace of 2-3 letters per week. The Boot Camp will prime the kids, exposing them to the entire alphabet in only one month, and the 2-3 letters per week introduction will allow deeper learning and practice to take place the next two to four months (depending on whether you teach 2 or 3 letters a week). This then provides the possibility of using the remaining 2 to 5 months to fine tune letters-sounds that weren’t mastered and dig into patterns, starting with CVC words and also incorporating digraphs. And since we’re on the topic, you may want to put a bug in your district’s ear about the sequence. If I remember the Journeys sequence correctly, I’m not the biggest fan. It unfolds (like you said) with a letter per month (too slow!), doesn’t introduce a second vowel (letter i) until about halfway through the sequence, and places the X and J before E, which I think is downright odd. Perhaps I have this wrong. If I have it right, you could keep the Journeys sequence but move letters around to make it more effective. FYI and BTW, here’s the sequence from UFLI (University of Florida Literacy Institute) - I’ve become a fan! It starts out like Journeys but then gets interesting (and more effective): a, m, s, t, VC/CVC, p, t, f, i, n, CVC (with a, i), an/am, o, d, c, u, g, b, e, s (s), s(z), k, h, r, l, w, j, y, x, qu, v, z In Conclusion In kindergarten, as you seek to more effectively teach letters, sounds, and words in kindergarten, all of which are used by young children to spell, write, and read, consider these following thoughts:

In Norman Fischer’s world of Zen, an “entire culture of practice” includes the performance of rituals, the building of relationships, and the actions of study. In the world of elementary school classrooms, I believe the same elements can be and should be present. Previously we discussed the classroom actions that produce specific reading and writing skills and categorized them into three broad categories: teaching techniques, classroom activities, and student-used strategies. When viewed in terms of “culture,” we see these techniques, activities, and strategies as a way of life, used weekly, daily, and hourly, year after year. But what of rituals and relationships? Rituals For me, ritual encompasses tradition, rite, habit, and ceremony. Regularity is paired with beauty and mystery, helping to keep daily efforts from sliding into dull and dreary routines. In classrooms, incense and candles would boost engagement but I bet they’d also collide with allergic reactions, classroom fires, and parent protests. Not a good mix. So, what else could classroom rituals be? The ritual of sustained writing in special spaces, which could include:

In gentle numbers time so idly spent; Sing to the ear that doth thy lays esteem, And gives thy pen both skill and argument. The ritual of sustained reading and reflection:

Relationships

Within communities, from temple to church to classroom and school, we find relationships - the last element of our “entire culture of practice.” To get you started, I offer these “building relationships” ideas. I know you’ll think of others! Relationships between teachers and students, including:

Relationships between students (harnessing the social nature of children in service of education):

Grandiose actions can foster relationships. Here I am thinking of things like taking trips to the library and reading in a continuing-care community. But smaller actions can connect children to larger communities, too. For example, if you stock your classroom with plenty of books that feature characters who look like the diverse readers in your classroom, you’ll be connecting your students to Black communities, rural communities, Native American communities, suburban communities, Asian communities (Hmong, Vietnamese, Indonesian), and so forth. These books come from a recent issue of NEA Today:

Conclusion Over the course of two blogs, we’ve investigated literacy elements – from teaching techniques and classroom activities to rituals and relationships– that together, over months and years, form a “culture of practice.” What is this culture of practice leading to? What is its purpose? In Norman Fischer’s world of Zen, a culture of practice ultimately leads to a shift in the practitioner's understanding of his life, a greater ability to love. and personal transformation. In a first or fifth grade classroom, the shift can be equally profound. Through the unceasing actions of dedicated, professional teachers, students grow to see themselves as human beings with agency and a strong sense of themselves as readers, writers, thinkers, and learners.  While reading Norman Fischer’s book, When You Greet Me I Bow: Notes and Reflections from a Life in Zen, I was struck by the phrase “culture of practice.” Fischer uses it to describe how Zen Buddhist’s go about cultivating enlightenment, reminding the reader that practitioners don’t magically transport themselves to greater compassion, open heartedness and enlightenment. “No,” Fischer says, “The entire culture of practice is necessary… including meditation, study, relationships, ritual, and much more.” My mind quickly jumped to the world of teaching. Aren’t we engaged in creating a culture of practice in our classroom? And aren’t we, step by step over time, leading students to a form of enlightenment, including an illumination of how reading and writing work, a comprehension of all types of text, and a deeper insight into the world around them? For me, the answer is yes! At first blush, it seems like a lot to master. But with repeated practice, good teaching habits take root and grow. And if I focus on activities rather than passive worksheets and lectures, incorporating everything isn’t so daunting. For example, here’s a list of activities that, when used in combination over the course of a week (and a month and the year), help to create fluent readers, writers, and spellers:

Reading books of choice, pulled from easily accessible bins and boxes (grouped by genre, author, and/or theme). Like writing on topics you choose, reading a book you choose fosters engagement and motivation. What about the strategies students use to solve problems and deepen their understanding? It’s another long list but I think we can identify some especially important ones:

Wow, our lists are getting long! And we still haven’t covered the “entire culture of practice.” What about the rituals and relationships Fischer mentioned? Stay tuned for Part Two! Effortless reading is essential to comprehension: when students read fluently – with high degree of accuracy, at a good rate, and with a large dollop of expression – their cognitive efforts go into gaining meaning from words, rather than simply recognizing them. In the previous blog, I described Jay Samuel’s Repeated Reading routine – a formal procedure that builds text fluency and includes a prescribed process for picking goals, correcting errors, and reflecting on reading behaviors and strategies. But in this blog, I will look at a less formal routine, namely I Read, We Read, You Read, as well as informal re-reading activities done by students during independent reading time. First up, I Read, We Read, You Read. I Read, We Read, You Read is a Type of Guided Repeated Reading As a bit of review, guided repeated reading differs from independent repeated reading in that it gives readers support via guidance from either a teacher or peer. In the case of the I Read, We Read, You Read routine, the guidance comes from the teacher. During any small group reading time, a teacher might devote some time to the teaching of a a comprehension or decoding strategy. Then, as students read, the teacher might coach the readers in the use of that strategy. Afterwards, the group might discuss the reading, ask and answer questions, summarize, and/or review how the strategy played out during the reading. Another follow-up activity might be “I Read, We Read, You Read.” I Read, We Read, You Read doesn’t need to take much time. Five to seven minutes should be more than enough. Before the activity, though, take note of any sentences or paragraphs students had difficulty decoding. These will then be the focus of repeated reading. During the “I Read” phase, tell the students you are going to read a paragraph with “expression, very few mistakes, and at a speed that sounds like talking.” Ask your students to follow along (perhaps using fingers to track or a cover sheet) as you read the target paragraph. Then read it, with a lot of expression, a high degree of accuracy, and at a rate that is not to slow or fast. Next comes, “We Read.” This is the choral reading part. Tell your students to read the paragraph out loud with you. As you read, see that they track the words carefully and match your expression and speed. If you notice mistakes from one or more students, repeat “We Read” one more time. Finally, it is their turn to read. The command “You Read” is the echo reading part. As before, tell your students to read the paragraph one final time. Remind them to track the words carefully as they read and to stay together, matching each other’s phrasing, expression, and speed. All of this can take place with the whole group or in a small group. The picture below shows an independent reader re-reading a book while children in the background do choral and echo reading with their teacher. Engaging Independent Activities for Re-Reading Text If you offer engaging re-read activities, students may enjoy reading the small group text one more time. Or perhaps they will want to read a paragraph of their own choosing multiple times. In Paintbrush Reading, students pull a small paintbrush from a box or can of brushes and then pull the paintbrush under the sentences they are reading. They re-read the sentences multiple times, pulling the brush under the words each time, until they able to read the sentences smoothly, in phrases, at a good pace, and with expression. To see someone model this type of reading, click on this Paintbrush Reading link. Another option is to put a number of social and emotional learning cards, like these, in a pile or box in the independent reading center. During independent reading time, students can pull a card and then practice reading their text in an emotional way, as dictated by a card. For example, they might pull the sad card or the angry card or the joyful card. I suggest you take out the distracted and tired cards! Also, Chris Biffle, creator of Whole Brain Teaching, has a re-reading activity he calls the Crazy Professor Game. Click on this LINK to see the “game” in action – you’ll want to skip ahead to the time mark of 1:42. One final easy and engaging independent reading activities is Read to the Wall, whereby children get out of their seats and take their book or poem to a spot along a classroom wall. While facing the wall, they read and read again a passage from their book. This activity gives children a chance to stand and stretch, as well as do something different. Facing the wall accomplishes two things: 1) students reading quietly can still easily hear their voices because the sound waves are instantly reflected back from the wall to their ears, and 2) facing a wall promotes concentration and focus. In conclusion Repeatedly reading a page or paragraph can improve a student’s ability to read automatically. From a teacher using echo and choral re-reading to a student re-reading independently to the wall or with a paintbrush, there are many ways to do this beneficial practice. One point of instruction to stress is to “read with accuracy and expression (reading quality)” rather than focusing students strictly on words per minute (speed). A certain amount of rate is helpful, for sure, but reading words accurately will help comprehension even more. And reading with inflection and phrasing also is a hallmark of reading that involves deeper comprehension. As teachers, we are thrilled to hear students reading with flow and expression. While the sound of fluent reading is beautiful in and of itself, we also know that effortless reading is beautiful because it is essential to comprehension. When students read fluently – with high degree of accuracy, at a good rate, and with lots of expression – their cognitive efforts go into gaining meaning from text, rather than recognizing words. Fluency instruction can take many forms, but it typically involves having students read orally. This allows teachers to hear how the text is being processed. In some cases, students read the same page or paragraph multiple times, which may improve a student’s ability to read automatically. But repeated reading is not the only game in town. In other cases, students read new text in a non-repetitive manner. When done with specific supports, this type of reading also builds fluency. Over the next few blogs, we will look at instruction that builds a student’s fluency. The general categories of instruction are 1) repetitive or repeated reading and 2) supported non-repetitive reading. Up first, Jay Samuel’s Repeated Reading, a specific form of guided repeated reading. Guided Repeated Reading

Guided repeated reading differs from independent repeated reading in that it gives readers support via guidance from either a teacher or peer. There are a variety of guided repeated reading routines and they exist on a continuum of highly formal to informal. Let’s first discuss a formal one pioneered by Dr. Jay Samuels and aptly titled Repeated Reading. Across many decades, Repeated Reading has shown strong evidence for improving the oral reading fluency of students, from elementary to secondary, from typical learners to students with learning disabilities. Typically, during Repeated Reading, students orally read a single passage multiple times to reach a certain percentage of accuracy rate, or to complete a prescribed number of readings. For example, students might be instructed to repeatedly read a passage until reaching 130 words correct per minute (WCPM). But because rate can be overrated and helps comprehension only up to a point, other goals should be considered. More on this in a minute. Key components of Repeated Reading Researchers have identified several key components of Repeated Reading instruction.

As mentioned earlier, goal setting can involve a student picking numerical goal, such as “I will read 120 WCPM on my third reading of the passage.” But studies shows that during guided repeated reading with student coaches, some peers consistently recorded inaccurate reading rates. In addition, goals that stress the number of words read correctly per minute may communicate that speed is more important than quality! So, some researchers recommend that students be taught to focus on other quantifiable reading behaviors, as well as reading strategies. Examples of these behaviors and strategies include:

Repeated Reading Lesson A typical session of Repeated Reading involves the following:

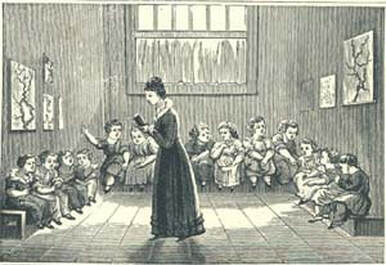

For more details on all of this, from a teacher’s introductory lesson and a peer’s coaching to the science behind the procedure, check out the full Iowa Center for Reading Research article at iowareadingresearch.org/blog/repeated-reading-fluency. And remember these two important ideas as you think about how to build fluency: 1) Fluency is built through the rehearsal and refinement of word recognition, and 2) a what is most important is a focus on reading quality rather than reading speed. Sources Women’s History Month is here, providing space to celebrate and reflect on the contributions of women over the years. In the area of reading instruction and research, women have consistently been at the vanguard of formulating reading theories, testing them through study and experimentation, and using them to build classrooms practices that teach children to read, write, and spell. As I think about women in history, I believe reading research is an area of science where women have consistently shone across the many decades. Reading Researchers Historically, women were not welcome in sciences such as physics, astronomy, chemistry, and medicine. Of course there were outliers – Marie Curie, Elizabeth Blackwell, Jane Goodall and Rachel Carson come to mind – but by and large, women were not encouraged to pursue or even allowed to enter scientific studies. But in the sciences of education and reading, this was not the case. When I think of those who have contributed to my understanding of what reading is and how I can best teach it, my thoughts quickly go to a list of women, including Elfreida Hiebert, Dolores Durkin, Dorothy Strickland, Margaret McKeown & Isabel Beck, Linda Gambrell, Catherine Snow, and Mary Anne Wolf. From thematic teaching and vocabulary instruction to reading comprehension and the neurobiology of the reading brain, the work of these researchers helped me to see that seemingly disparate parts of reading are actually facets of a complex and sparkling whole. Equally important, their insights have allowed many, including myself, to develop routines, activities, and curriculum that increasingly give all children a greater chance of becoming fluent readers, writers, and spellers. The list above doesn’t include my all-time Big Three of reading researchers. That trio would be Louise Rosenblatt (the transactional nature of reading), Jean Chall (stages of reading development), and Linnea Ehri (the essentiality of orthography), all of whom I’ve mentioned in previous blogs. If you don’t know these scientists, I encourage you to look them up, read about them, and reflect on what they’ve brought to the teaching of reading. Dorothy Strickland Maryanne Wolf Linnea Ehri A small sample of powerful reading scientists/researchers Women as Teachers As I reflect on reading researchers, I can’t help but wonder about the role of American women in education and how their progress in the field of teaching has ebbed and flowed over time. According to a pithy article in The Western Carolina Journalist, prior to 1850, teaching was a career dominated by men. But enormous social changes in the latter part of the 19th century brought about an almost complete reversal. As industrialization lured men into money-making businesses – building and running railroads, managing factories, trading in the stock market – thousands of teaching positions opened up. At the same time, immigration brought more children into cities, creating a demand for more teachers. Over the decades, women in education, who now comprise more than 80% of all teachers, made better wages, achieved status, and gained freedoms and opportunities to further their careers. They also suffered through large classroom sizes, meager pay, and burdensome oversight from male administrators. To this day, advancement continues to march forward and lurch back. Unions, as well as changing societal norms, have helped women achieve economic protections, better working conditions, more career education, and organizational positions such as curriculum directors, principals, superintendents, and senior researchers. But at the same time, some in the greater world still see teaching as “women’s work” – a belittling and ignorant phrase – and pay for women in all fields, including education, continues to lag behind that of men. An early teacher

Illustration via American Antiquarian. Those Who Can, Teach Finally, I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention my mother, an educator and lover of science. She was a huge influence on what I’ve learned about the teaching of reading and her career journey reflects both the joys of teaching and the struggles of women to be truly free and equal. As a young woman, she showed a keen intellect and a knack for observation of the natural world. She was interested in the sciences and in high school garnered a science scholarship to attend Temple University. But my grandfather, a school principal at the time, discouraged my mother’s love of science and desire for advanced study, instead strongly suggesting that she study nursing (the profession of my grandmother) or teaching. In the end, my mom choose teaching, attended a local Pennsylvania Teachers College, and had a long and satisfying career as a most excellent teacher, teaching as a reading specialist, a university professor, and a first grade teacher. Like many women, her accomplishments were astounding and included the raising of three children, running the family’s day-to-day operations, sometimes being the major bread winner, managing classrooms of rambunctious elementary-age boys and girls, and teaching the essential skill of reading to hundreds of children, thus changing their lives forever. So, here's to the women of the world, to the teachers and researchers, and to all those working to help people everywhere become more educated and open minded! Sources Artificial intelligence is big news. Over the last three months, I’ve taken in a half-dozen podcast episodes on the subject, as well as heard and read reports from NPR, CNN, The Guardian, Reuters, and The New York Times, just to name a few. According to some, AI-powered chatbots are set to replace everyone from counselors and journalists to Broadway-bound playwrights. Even 4th grade writers may become a thing of the past! And what of teachers? Could AI-powered robots replace us? More importantly, should they?

Setting the Stage After presenting at a recent reading conference, I was approached by a researcher who told me she was working on robots capable of teaching reading skills. My first thought was, “That’s crazy talk. Who would want that?” But as I listened to the professor speak, and later, as I reflected on what teaching efforts are required to teach readers who struggle, I found myself thinking yes, robots could teach important reading skills and yes, I am open to the possibility of AI-powered programs and robots that teach certain components of reading. There are, of course, many excellent reasons why robots and AI should not replace humans in the world of work. From a humanist viewpoint (all technical, historical, ethical, and equity issues aside), my reasoning is fairly simple: 1) jobs and careers often bring dignity and a sense of purpose; 2) humans thrive when they have both; 3) if we allow intelligent robots to take our jobs, our ability to live purposeful, thriving lives will be greatly diminished. But if we consider AI as a supplement to what humans do rather than a replacement, then my opinion changes: I think it could be somewhat to very helpful to have robots and AI in our world. For example, robots and artificial intelligence are already hard at work in medicine, quickly and accurately spotting malignant tumors, transcribing doctor-patient interactions, assisting with prostate surgery, and designing previously unimagined molecules and proteins for new lines of research and drug therapies. Obviously, artificial intelligence is now at the point where it is able to perform certain technical tasks better than humans, in ways that are increasingly beneficial to its human masters. In the field of education, robots and AI might function in the same supplemental way, teaching skills that require a lot of repetition for mastery, supporting students during independent work time (when a teacher is engaged with a small group), performing formative assessments and designing maximized-for-learning follow-up lessons. Let’s consider these more deeply, starting with repetition. Go Back, Jack, Do It Again As part of my one-day seminar on dyslexia, I present seven teaching techniques useful for teaching all children to read and especially helpful when teaching students who struggle. The first is repetition, a technique common to all effective teaching and a prominent part of tried and true reading interventions such as Wilson Reading, 95%, Corrective Reading, and so forth. Teachers using the Orton-Gillingham program sometimes refer to repetition as “relentless redundancy” but no matter what you call it, when combined with distributed practice, repetition is a foundational component of effective reading instruction, especially when it comes to teaching students on the dyslexia continuum. To become fluent readers, children MUST break the code and for some it will take dozens of repetitions to form sound-letter relationships. Therefore, repetition is a necessary part of their reading instruction. Like everything positive, repetition comes with challenges. One is to avoid the drill and kill trap, where a teacher and/or program uses the same materials and activities over and over again for too long of a period of time, thus boring the student and possibly the teacher. Once boredom sets in, distraction and irritation follow, along with decreasing levels of learning. Thoughts About Bots One way to minimize “repetitive equals boring” is to use a variety of activities that teach the same concept or skill repeatedly over time. Enter intelligent robots! In situations demanding high degrees of repetition, such as teaching sound-letter associations, decoding skills, and spelling patterns to students who struggle to learn, non-human instructors could provide efficient and effective instruction. For students, the instruction would be novel and engaging. Many children might be tickled to spend 1-on-1 time with a robot or an especially clever and chatty computer program. And as we know, motivation and engagement are huge factors in how much a student learns. So, anything we can do to motivate and engage is a good idea. As for teachers, there are many possible benefits. First, for some teachers, repetitive intervention programs are problematic (i.e. uninteresting). But robots don’t mind repetition (in fact, they don’t “mind” anything at all). Second, a robot running skill practice with an individual student or small group would enable a teacher to work with other students, individually or in small groups. Third, robots don’t have feelings, one way or the other, for any particular reading program and so their ability to carry out a particular methodology isn’t influenced by how they feel about it. Finally, artificial intelligence can easily gather, manage, and translate large amounts of assessment data, an ability that could free teachers to concentrate on the big picture of classroom achievement. Speaking of data translation, AI is already capable of crafting future lessons that take into account past response patterns, thereby allowing for the fine-tuning lessons for individuals. This targeted instruction can lead to greater student learning in a shorter amount of time. In turn, students who quickly learn basic skills feel less frustrated and more happy. These happy feelings then feed positive feedback loops. Nothing succeeds like success, right? Equally important, less time spent on drilling skills (because students learn more efficiently) means more time spent on other important educational endeavors, such as exploration, discovery, discussion, and synthesis. Conclusion As Paul Simon sang in The Boy in the Bubble, “These are the days of miracle and wonder.” Technology, as always, is showing up in our world, whether we are ready or not. And so it behooves us to start carefully considering how, when, where, and especially why we want to use those intelligent robots. Here is a fact: Journalist Emily Hanford helped popularize the term “Science of Reading,” Some would call that fact a dead fact. Here’s another fact: It takes some children hundreds of repetitions to associate a sound with a letter. I call that fact a live fact. Okay, here’s another dead fact: The term dyslexia is made from two Greek roots, dys, meaning “difficult or inadequate,” and lexis, meaning “word.” Now, another live fact: Teaching students the six syllable types can increase their chance of mastering encoding and decoding. Are you starting to see how dead and live facts differ? What is a dead fact? In his thought-provoking book If Nietzsche Were a Narwhal: What Animal Intelligence Reveals About Human Stupidity, author Justin Gregg explores how unique human cognitive abilities, such as mental time travel and creating moral systems, are double-edged swords, each as likely to lead to individual suffering and world catastrophe as to personal contentment and a livable future. In one chapter, Gregg introduces the term dead facts. Coined by philosopher Ruth Garrett Millikan, dead facts have to do with the human brain’s tendency to elaborate and expound upon (to think thoughts about) incoming sensory information. To understand just what a dead fact is, let’s first consider a nonhuman brain and its reaction to sensory input. For example, if I were a rabbit and I heard a loud rustling behind a nearby tree, I would bolt in the opposite direction. Why? As a rabbit I know this fact: rustling equals danger. And so I run! Most animals that hear rustling probably don’t think anything more than rustling equals danger. Humans, however, are different. My human brain might quickly move from “rustling equals danger” to thoughts about why the rustling is happening. It's a fox, I think, or a falling branch. Or maybe it's a coyote. Could it be a wolf? Just as quickly, my brain might fabricate more improbable thoughts. For example, I might remember the time I played hide and seek with my sister, who was hiding behind a tree. Then I might think, “Wouldn’t it be crazy if my sister is making that rustling sound?” Cooler still, I might wonder “What if the rustling is caused by a lost extraterrestrial or a sasquatch, hiding to avoid detection?” For humans, these recollections and imaginings are simply how we roll – one event occurring in our environment can trigger the remembering of countless bits of trivia and the dreaming of endless stories of fiction. Ruth Millikan called these kinds of thoughts dead facts because they have nothing to do with our acting on incoming sensory data in ways that boost our chances of immediate survival. This is not to say that our wishful thinking and imaginative musings don’t have a place in the world. I enjoy thinking weird and whimsical thoughts. And ever-evolving thoughts and connections often lead to innovations, solutions, art, and religions. But when it comes to the efficient solving of an immediate problem, fabrications, ruminations, and the random recall of trivia can distract us. Which leads me to reading instruction. Live Facts for Reading Instruction

Yes, facts like “journalist Emily Hanford helped popularize the term science of reading” and “the term dyslexia is made up of two Greek roots” are fun to know. But they are of no use to me when comes time to teach kindergarten students sound-letter associations or help a dyslexic adult become a more fluent reader. Thus, I want to stay focused on live facts, the ones most useful in my day-to-day instruction and capable of lifting my teaching to the most effective level. Here are some live facts I strive to keep in mind:

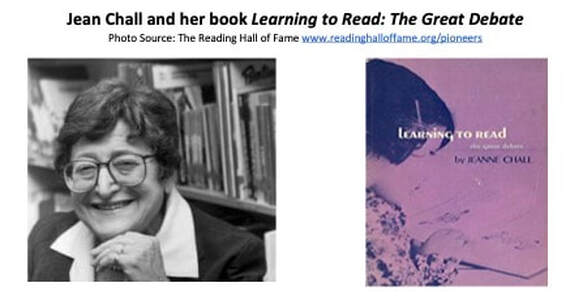

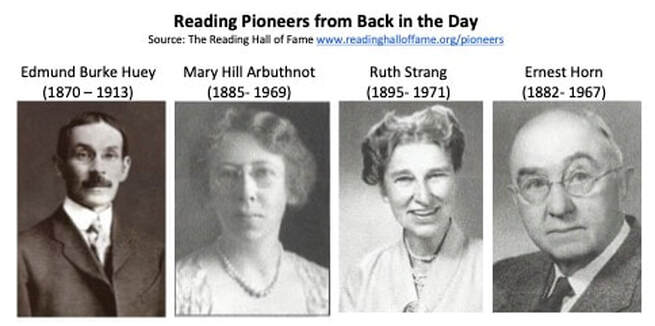

In conclusion, when it comes to reading instruction, consider the facts and decide which ones are dead and which ones are live. Then give the live facts priority! Review them on a regular basis and keep them in a brain space that is easily accessible. Finally, use them as the foundation of your reading, writing, and spelling instruction. When instruction is built upon a firm foundation of live facts - facts that enable efficient and effective teaching - students more easily become thriving readers, writers, and spellers. Source: Unsplash

This post was specially written for MarkWeaklandLiteracy.com By: Reina Janice In recent years, digital technologies have occupied a huge space in education. For example, our post on using ‘The Slide Show to Build Language Comprehension’ talks about how a modern slideshow can convey so much information in an engaging way. Compared to previous decades, where available images could be limited or outdated, slideshows are a tool to add new words and their corresponding meanings to a child’s mental lexicon. Based on Maryville University’s description of American education, digital innovations are also rapidly transforming the way we approach learning. Around 21.1% of public schools offer at least one purely online course, while 90% of teachers believe that classroom technology is important to student success. However, 60% of teachers also report that they are “inadequately prepared to use technology in classrooms.” Many instructors need to keep up with shifts like swapping textbooks for tablets to effectively prepare students for a high-tech future. One area of concern, in particular, is whether or not reading in a digital format affects comprehension. Reading is not a natural skill, and it takes real work for us to master it. Unlike learning to talk, which we absorb by listening to others, the brain doesn’t have a special network of cells exclusive for reading. Instead, it borrows networks that evolved to do other tasks. For example, brain circuitry that evolved to recognize faces is used in reading to recognize letters. This flexibility is beneficial, but it can be a problem when reading different types of texts. When we read online, we use a different set of cellular connections from the ones we use to read in print. In this article, we’ll look at how reading in digital formats can affect comprehension and how to help students read across mediums. Reading a screen makes us faster readers – but not in a good way Reading on a screen often involves skimming, scrolling, browsing, and scanning. There is a sheer volume of content available online, which invites us to read quickly without going in-depth. As the University of Washington’s study on social media points out, we often enter a dissociative state when we scroll online and stop paying attention to what we’re doing, so sometimes we don’t even remember what we read on our phones. We’ve also gotten used to short reads like text messages or Tweets that don’t require much effort to understand. Living in a fast-paced digital world can change younger students’ brain plasticity and influence their ability to improve in comprehension, since the environment rewards shorter attention spans — even if we’re not absorbing ideas well. Digital reading can lead to shallow processing A research on smartphone reading published in Scientific Reports discovered that reading on a smartphone can promote brain overactivity in the prefrontal cortex, leading to poor narrative content comprehension and lower cognitive performance. It’s possible that the amount of digital stimuli — ads, updates, emails, texts — places a heavier visual load on our brains. In comparison, reading in print is less visually demanding. There are spatial and tactile cues that help us process the words on the page. For example, while reading in a digital format, readers can only navigate through text left to right and up and down. But a physical book gives spatial cues in three dimensions: left-right, up-down and forward and backward, across pages and entire chapters. Digital reading is also less likely to foster habits like reflection and note-taking, and a gap in these habits can limit overall comprehension. Some training is needed to read digital text effectively Researchers at the Complutense University of Madrid note that when eBook materials are properly selected and used, young children can develop literacy skills equally well and sometimes better than with print books. eBooks are more accessible, after all. Those with reading disabilities can adjust the font size, background color, and typeface for ease. And you can highlight the text, take notes, or visit links to additional resources. It just takes some training to better engage with digital text. For younger readers, they can try to summarize what they’ve read orally, while older children can reflect through writing. The key is to be mindful and strategic when interacting with whatever we read. Specially written for MarkWeaklandLiteracy.com By: Reina Janice I love reading. It informs me, whisks me away to other worlds, entertains me with gripping stories of love, adventure and redemption. I love science, too, because it thrills me with descriptions of billion year-old life forms and humbles me with deep-space photos of a million spinning galaxies. So, I was delighted to discover a few years ago something called the Science of Reading. “It’s science and reading combined,” I cried, “like sweet chocolate and peanut butter in a Reese’s Cup! What could be better?” But I must confess that lately, when I see that capitalized label stamped on book covers and classroom materials, I am surprised to hear my inner skeptic whispering words of caution. And I can’t help but think of that quote from the American philosopher Eric Hoffer: “What starts out here as a mass movement ends up as a racket, a cult, or a corporation.“ To ensure the Science of Reading avoids this fate, let’s consider how we present the science behind the teaching of reading. I’ll kick off the consideration by sharing two things on my mind: honoring our reading history and avoiding the bandwagon. Honor Reading History Scientists (aka researchers) have been shedding light on the subject of reading for a long time. This is true for both theories that describe what reading is and instructional practices that bring it into being. Sixty-five years ago, Harvard’s Jeanne Chall wrote Learning to Read: The Great Debate and the subject it surveyed was the fifty years of reading research that occurred prior to the book! Around now for at least 115 years, the science of reading is nothing new. That, of course, doesn’t mean reading science has nothing new to offer us. For me, the information bundled as the capitalized Science of Reading is exciting for a number of reasons. First, by highlighting the workings of the human brain (and the mind that arises from it), it brings new information and energy to old ideas. Second, by emphasizing particular aspects of reading, it makes effective instruction more possible, specifically because we have increased our focus on teaching phonology and orthography, using explicit and systematic instruction, and melding language comprehension and automatic word recognition. But although the capitalized label is relatively recent, much of the information that supports the Science of Reading (SoR) is not. Regarding the research that supports the movement, the work of (among others) Linnea Ehri, Philip Gough & William Tunmer, Jeanne Chall, and David Share goes back forty or more years. Also, many important areas of reading research that have lead to effective classroom practices are not officially part of SoR. These areas include studies on the transactional nature of reading, the importance of writing, the role of motivation in reading, the function of authentic and diverse books, and the value of differentiation. And here’s something else: just because a practice like literature circles or a philosophy like balanced literacy lacks science in its title, that doesn’t mean it isn’t based on some scientifically derived insight. Nor does it mean that the practice or philosophy isn’t worthy of classroom use. To summarize, the specific scientific ideas promoted by the Science of Reading, and the classroom practices that flow from this promotion, are tremendously important. But there are other important classroom practices to incorporate into our reading instruction and as an educator deeply involved with the lower case science of reading, I owe a debt of gratitude to the scientists who have brought forward all of these important practices. Beware the Bandwagon Also beware the cult and the pendulum swing. All are created when a group of people, from reading specialists to a school board or publishing company, too fully embrace a particular set of educational ideas while rejecting others. The end results include money wasted, conflicts created, teachers confused (and turned off), instructional effectiveness diminished, and worst of all, students who don’t learn what they need to learn. Recently I’ve been wondering if our field’s tendency to jump on a bandwagon is due in part to labeling. Any educational label – from guided reading and balanced literacy to the science of reading and structured literacy–collapses a rich body of thinking into just a few words. Thus, labels perform a useful function, allowing us to quickly grasp and remember the details of intricate, multi-faceted subjects. Perhaps labeling is part of our brains’ amazing ability to create schema: one thing is attached to another, which is also attached to another and another. Conjure up one strand and very quickly an entire tapestry comes into focus. But catchy labels are double-edged swords: they can lead to simplistic and fuzzy thinking, blind allegiance, and corporate greed, all of which can keep large numbers of children from learning how to read. Lucy Calkins, the well-known educator and creator of Units of Study, seems to have been effected by all three (as described in a 5/22/22 NYTimes article), embracing her own theories and data too fully, excluding other important data sets too completely, and concentrating too much on product production and not enough on product effectiveness. Perhaps this explains how and why a thirty-year giant in the field has only recently embraced the idea that teaching phonemic awareness and spelling-phonics to mastery levels is a critical part of any foundational reading program. Sadly but not surprisingly, the Science of Reading may be suffering from the same effects. Scroll through the #scienceofreading Twitter feed and you’ll see blindly allegiant Tweeters angrily tagging others as idiots, the enemy, or both. And recently a friend mentioned a meeting he had with an educator who demanded more fidelity to the Science of Reading message and more publications flying its banner. To my friend, the encounter felt “like a witch hunt.” As for money making, I have on my computer desktop The Reading League’s defining guide on the Science of Reading. According to the League, the Science of Reading is definitely NOT a program of instruction or a one-size-fits-all approach. But also on my desktop is a Science of Reading product, available from Teachers Pay Teachers, that very much looks like a program of instruction that feed a one-size-fits-all approach. Products such as these, each promoting their particular version of the Science of Reading, proclaim that balanced literacy “teaches with no pre-determined scope and sequence,” “presents spelling as if words are remembered by sight,” and “does not address orthographic mapping.” I know many excellent teachers, teaching in “balanced literacy” schools, who say nothing could be further from the truth! In a World of Riches, Why Be Binary? Sadly, our nation is plagued by divisions. Media reporting repeatedly uses the word “war” to describe our political, cultural, and economic differences. I don’t agree with the use of that term and I certainly don’t believe there needs to be some horrific struggle over how to teach reading. Rather, there is room for sharing and synthesis because we know what works. In fact, I see this sharing and synthesis all the time. The field of reading is blessed with more scientifically-derived support than any other elementary school subject area. Again- there is much agreement on what works. So don’t sweat the tiny details. And certainly don’t let anyone say you have to choose one side over the other: direct and explicit spelling-phonics over shared reading, small group skill work instead of guided reading, decodable text rather than engaging picture books. Pick the best parts of each, basing your picks on the needs of your students, giving some students more of this and less of that. Finally, regarding the Science of Reading, let’s do the following: 1) connect the current Science of Reading movement to the long history of science in the field of reading, 2) show how SoR works with other science-informed bodies of classroom practice, and finally, 3) work to keep its message respectful, nuanced, and positive. The end result will be more reading success for more students.

|

Mark WeaklandI am a teacher, literacy consultant, author, musician, nature lover, and life long learner.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed