Letter Confusion and Reversals: Why do they occur and how can we help students overcome them?4/5/2021

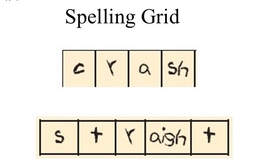

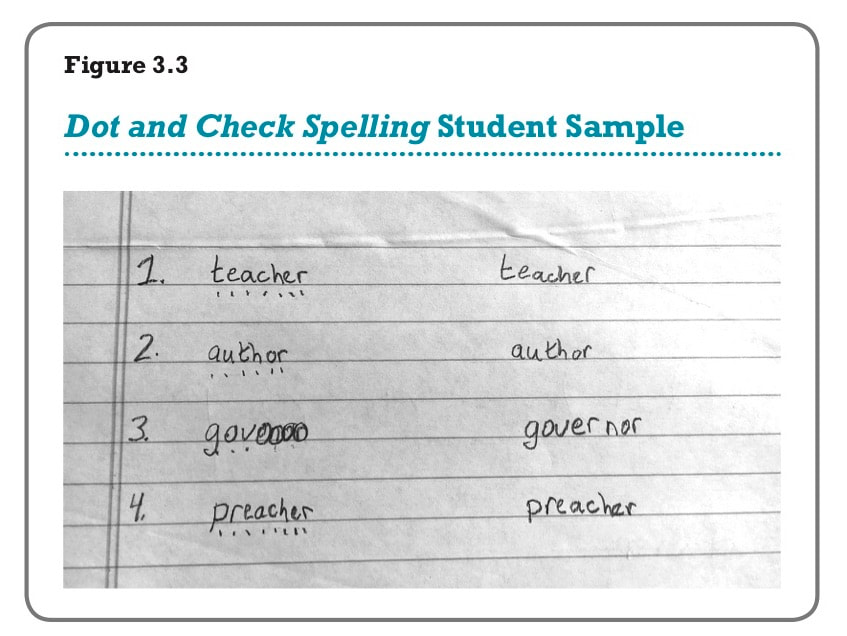

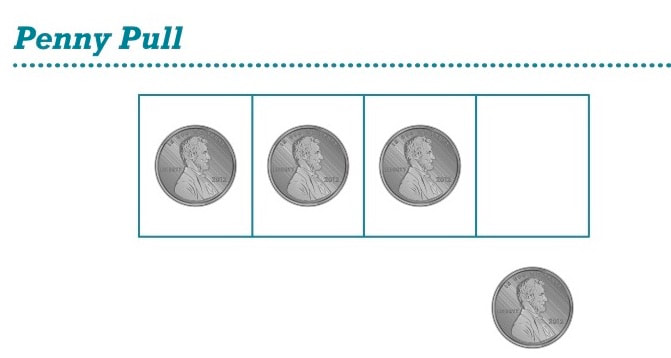

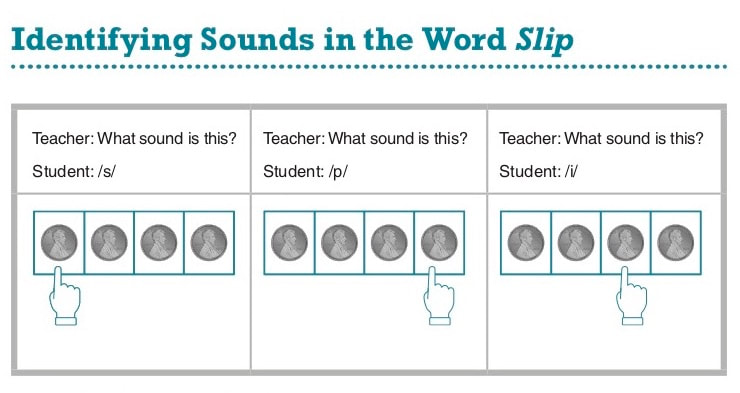

I had a big “ah hah!” moment when I recently reread Stanilas Dehaene’s book Reading and the Brain: The New Science of How We Read. In a chapter titled Reading and Symmetry, Dehaene, a French scientist who researches the neural basis of reading (among other things), explains why students often confuse letters such as b / d or d / p and sometimes read and spell words in reverse. It seems printing letters and words in reverse and reading certain words seemingly backwards typically has nothing to do with visual perception or visual memory. Rather, these things most often have everything to do with something called mirror generalization. Human brains Like all animal brains, human brains have evolved in relationship to their environment and physiology. Because we live with gravity, our brains can quickly realize that up is very different from down. Also, because our eyes are fixed in the front of our head, our brains know that ahead is very different than behind. But what about left and right? Consider these three objects, which are presented in Dahaene’s book. Do you recognize them instantly? Did you initially notice they were spatially backwards? In real life they appear this way: Mirror generalization Mirror generalization (sometimes called mirror invariance) arises from our body’s symmetrical nature and can be defined as the brain’s ability to recognize objects regardless of their spatial orientation. Imagine you are walking through a tropical forest and you come upon a bunch of monkeys. Some of the monkeys face you, some face away, some are on your left, others are on your right, and a few hang upside down from tree branches. Regardless of their spatial orientation, you instantly recognize all of them as monkeys. Why? Mirror generalization! Through this generalization, our brains automatically recognize an object regardless of how it is spatially presented. A natural function found in children as well as adults, mirror generalization saves us time and energy and helps us survive. In other words, your brain doesn’t care if a tiger, for example, is leaping at you from the left or the right. You brain’s only concern is to instantly recognize the thing as a tiger and then trigger a response in your body – RUN! The same effect holds true if the object is a city bus and you’re stepping out from the curb – STOP! When it comes to letters and words, however, an object rotated in space is not always the same thing. For example, consider this object - b. In the reading world, this object is the letter b and it represent the /b/ sound. Flip it and it becomes something different. Now it’s the letter d, representing the /d/ sound. Rotate it and it becomes something different again, the letter p. Mirror generalization is why many young children often confuse d / b and may read was as saw or spell stop as post. Simply put, they have not yet learned to suppress their brain’s tendency to register rotated letter forms and reversed letter sequences as the same object. Here’s a Dahaene quote from a section of Reading and the Brain. Specifically it’s about dyslexia but it references all students. The underlining is mine: “As a matter of fact, letter orientation does pose specific difficulties for large numbers of dyslexic children, who often confuse “b” with “d.” However, these are problems that are present in all children and not just dyslexics…Furthermore, mirror errors peak at between seven and ten years of age, when children learn to recognize letters, and then vanish.… Visual difficulties do not seem to play a dominant role in most of them.” (page 295). Unlearning is the new learning To learn that an object in one orientation is a b, another a d, and in a third a p, children must unlearn mirror generalization. But this process of suppression (or unlearning) does not happen naturally. How does it happen? Like the unnatural act of reading itself, most children unlearn their tendency to see a d as a b and was as saw through the efforts of teachers. Through teacher instruction, the brains of students are subtly rewired and mirror generalization, at least when it comes to letters and words, is suppressed or unlearned. In the end, emerging readers and spellers are able to at first intentionally discriminate and later automatically discriminate between mirror letters like p / d and words like stop/ post , was/saw, and net/ten. How can we helps students? When it comes to helping students turn off their mirror generalization for letters and words, there are a number of things we can do, especially for students who have brain wiring that is resistant to suppressing or unlearning the tendency. Here are some suggestions, many of which are described and explained in my new Corwin book, How to Prevent Reading Difficulties, PreK-3: Proactive Practices for Teaching Young Children to Read. You can also find video examples of many of them on my YouTube Channel: https://bit.ly/MWLit_YT_Channel

A Final Thought Here’s why I used the words typically and most often in my opening paragraph. Earlier I gave this Dahaene quote, “…Visual difficulties do not seem to play a dominant role in most of them.” But Dahaene goes on to say this about some students identified as having dyslexia: “In a few rare cases, however, left-right confusion does seem to be the true cause of dyslexia.” (page 295). It seems one can’t completely rule out left-right confusion and mirror generalization as the root cause of dyslexic behavior in a very low number of students. If you are teacher who works with a student who is not responding to intense, frequent, and long-term reading interventions (such as Orton-Gillingham, LiPPS, or Barton), a team meeting and possibly more assessment are in order. Sources/Citations

Comments are closed.

|

Mark WeaklandI am a teacher, literacy consultant, author, musician, nature lover, and life long learner.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed