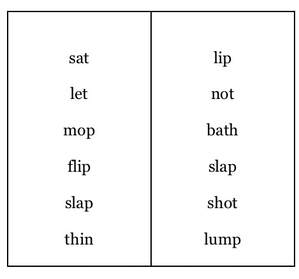

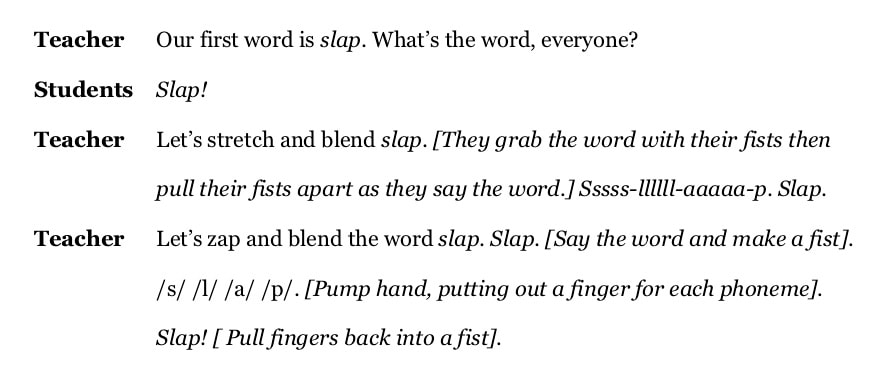

|

Human beings acquire language naturally, progressing from babbling babies to phone conversing adults with hardly a hitch. During our language development, we hear words spoken by others (our mother says “Look at the doggy”), we process these words via our brain’s meaning and memory functions (learning that “doggy” means the furry thing that runs around and licks our face), and eventually we speak these words to communicate our thoughts and feelings (we say, “I like the doggy”). Unless our language system is malfunctioning, the process develops naturally and effortlessly from the moment we are born up to and through our early childhood years. Reading and writing, however, are not acquired naturally. Although our brains come equipped with the necessary circuitry to read words (and conversely, to write words), someone must help us to train our brain circuits to perform the acts of reading and writing. This is true even for children who seem to acquire reading and writing skills effortlessly. To get kids to read and write, sometimes only minimal amounts of training and support are necessary. At other times, a great deal of instruction must be given, and support must be constant over many years. Regardless, learning to read and write begins with language (spoken words), moves to the understanding that words can be segmented into individual sounds (awareness of phonemes), and then progresses to associating letters and letter combinations with the phonemes of language to form words that mean something. At this point, letters and sounds can be combined to create basic words that can be read and written. When it comes to time to begin moving young children from listening and speaking to reading and writing, what instruction is most powerful? Four practices immediately come to mind: 1) phonemic segmentation and blending, 2) a carefully considered yet vigorous introduction of letters and their associated sounds, 3) repeated practice in printing alphabet letters and noticing the component parts of their written form, and 4) quickly moving from pairing letters and sounds to spelling and reading basic words. Today's post will focus on number one. Phonemic Segmentation and Blending: Stretch, Zap, Tap, and Blend Teaching young children to focus on the sounds of words (phonemes) is a critical part of early reading instruction. When it comes to early phonemic awareness instruction, get the most bang for your buck by focusing on instruction that teaches children how to segment, blend, and manipulate phonemes. A regularly-used routine of stretch, zap, tap, and blend is a practical yet powerful way to get that concentration into your instruction. The beauty of stretch, zap, tap, and blend is that the routine is also a strategy that children can use to both spell words (encode) and read words (decode). To teach it, begin with CVC, CCVC, or CVCC words, especially ones containing continuant letters that can be “held out,” such as the vowels, the consonants F, L, M, N, S, V and Z, and the digraphs SH and TH. For example, here is a list of words that work well for teaching stretching, zapping, tapping, and blending.  Begin by teaching your students how to “stretch the word.” Tell them a word is like a big rubber band. Model how to say the word, grab hold of either end of it (make two fists and hold them in front of you), and then slowly stretch it by pulling your hands away from each other as you say the sounds of the word, holding out the vocalization of each phoneme. For example, map becomes mmm-aaaa-p and flop becomes fffff-lllllll- oooo-p. After stretching out the word, say the word again and let the rubber band snap back. This shows that the sounds must be blending back together (quickly) to make a word. To combine stretching and zapping, I suggest this language, which gives the outline of a small routine you can repeat daily. Finally comes tapping and blending, a technique used by Wilson Reading. This technique involves the fine motor skills of tapping the individual fingers of one hand off a thumb. Thus, it may be too difficult for most kindergarten and some first-grade children. But it works for second grade children, as well as older children. The process for teaching the technique is much the same as zapping and blending. To model tapping, say a word like sock as you hold your hand up, your fingers loosely curled but not touching. Next, segment the sounds by saying each sound separately as you touch each finger to your thumb. The word sock gets three taps. The pointer finger comes down to the thumb when you say /s/. The middle finger down to the thumb when you say /o/. And the ring finger comes down for /k/. Finally, pull all the fingers to the thumb to blend and say the word sock. The Real Reason to Use It

According to the New York Times, the Taa language, spoken by a few thousand people in Botswana and Namibia, may have upward of 200 identifiable sounds! Most linguists believe that Taa has the largest sound inventory any language in the world. Thankfully, our English language contains a mere 44 separate sounds, ranging from /s/ and /ch/ to /oi/ and /ay/. Even better, research has identified some very effective ways to teach the sounds. Instruction that teaches young children to hear the individual sounds of English words and then blend them back together to make words is more effective than instruction that emphasizes alliteration, rhyming, and vocabulary. This does not mean you should not teach alliteration, rhyming, and vocabulary to young children who are beginning to develop reading and writing skills. But it does mean that you should regularly teach phonemic segmentation and blending in a concentrated manner, and you should give it more emphasis than alliteration and rhyming, as well as structured vocabulary lessons. Research that demonstrates the importance of phonology (the processing of sounds in general) and phonemic awareness (the understanding that words are made of discrete sounds, and the ability to manipulate those sounds) has been around for decades. In her book, Beginning to Read, famed reading researcher Marilyn Adams was one of the first to tell the public about the importance of phonology and phonemic awareness. A decade later, phonemic awareness rose to special prominence when the National Reading Panel put out its report in 2000. Since that time, researchers have bolstered the argument that phonemic awareness is a critical skill for future reading, and they’ve honed-in on the benefits of segmenting and blending. In his excellent 2018 article on early literacy research, D. Ray Reutzel cites numerous studies that clearly show that for younger readers, “reading skill is better predicted by phonemic skills than rhyming skills” and that phoneme segmenting, blending, and letter-sound relationships are “more likely to promote future reading ability than rhyming, alliteration, or vocabulary activities, even for highly disadvantaged children as young as 4 years old.” (Reutzel, 2018). Young students progress from being able to hear and say the sounds in words (in the initial, medial and final positions) to segmenting the sounds in words (and then blending them back together). And as they continue to develop, they can even manipulate the sounds in words, adding, deleting, and even substituting phonemes to make new words. Phonemic skills, however, don’t exist in a vacuum. They are co-dependent with phonic skills, an idea I'll explore in some upcoming post.

Comments are closed.

|

Mark WeaklandI am a teacher, literacy consultant, author, musician, nature lover, and life long learner.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed