Repeated Reading: An Efficient, Effective Practice That Helps Prevent Reading Difficulties5/20/2020

Reading fluency - the ability to read accurately at an appropriate rate and with proper expression and phrasing - is essential to reading comprehension (LaBerge & Samuels, 1974; Stevens, Walker, & Vaughn, 2017). Thus, it makes sense to use classroom practices that build all elements of fluency. Parents can also play a part in helping their children build fluency through reading activities. One especially effective and efficient practice is repeated oral reading. Repeated oral reading provides less skilled readers with the opportunity to hear a model of fluent reading and then practice it (multiple times) in a way that minimizes errors. Additionally, when students read together, especially with a teacher or parent, those who feel shy or nervous are supported, their stress of reading independently is lessened, and their self-confidence is boosted. Using the practice of repeated reading typically leads to improved reading performance, with the biggest payoffs being more accurate word reading, improved oral reading fluency, and more reading comprehension (Shanahan, 2020). The effect can be especially powerful for low performing readers (Zawoyski, et. al., 2014). Still, some schools don’t make use of this powerful practice. As dyslexia researcher Sally Shaywitz has pointed out “…the proven effectiveness of guided repeated oral reading to increase fluency is too often ignored. That is unacceptable. In fact, the evidence is so strong that I urge adoption of these programs as an integral part of every school reading curriculum throughout primary school” (Shaywitz, p. 233). Fortunately, it is easy to understand and then adopt the practice of repeated reading. Here are the key ingredients of the practice, as well as descriptions of a few variations. Key Ingredients All versions of repeated reading have a few key ingredients. They are:

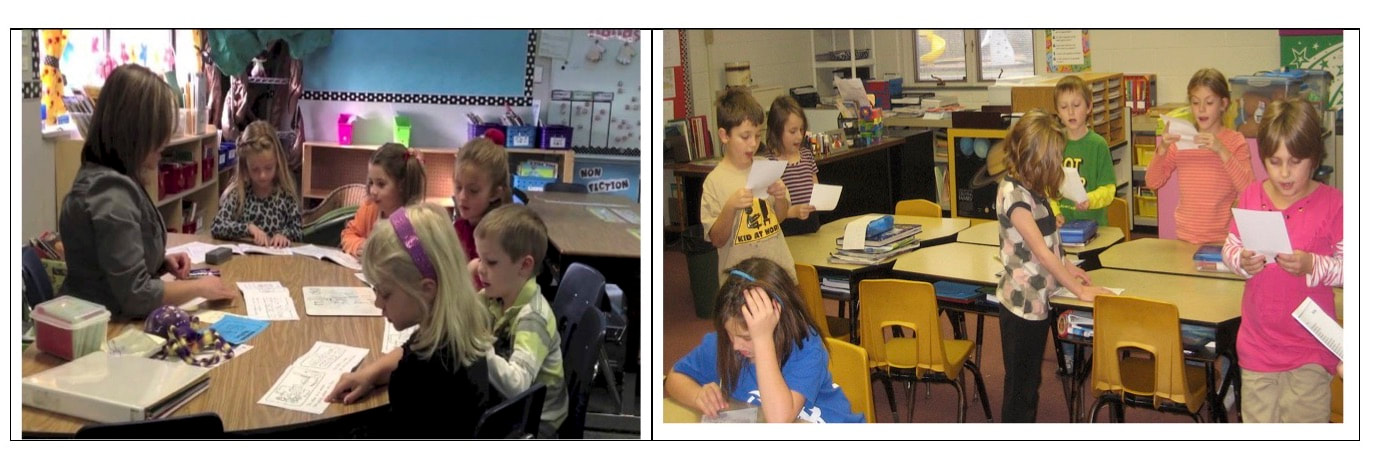

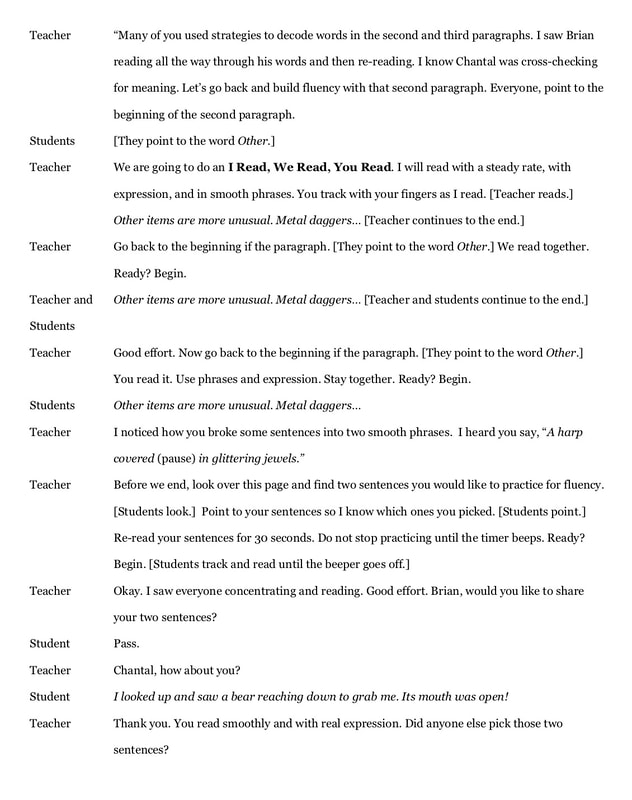

Repeated Reading Pioneered by reading researcher Jay Samuels, Repeated Reading been shown to be effective at improving the oral reading fluency of elementary students, including those with learning disabilities (Kim, Bryant, Bryant, & Park, 2017; Stevens, et. al., 2017; Lee & Yoon, 2017). This particular variety of the practice is capitalized because it is a specific routine. According to Timothy Shanahan, “Repeated Reading is a particular method … to develop decoding automaticity with struggling readers. In this approach, students are asked to read aloud short text passages (50-200 words) until they reach a criterion level of success (particular speed and accuracy goals)” (Shanahan, 2020). Key components of Samuel’s Repeated Reading go above and beyond the previously mentioned key ingredients and include instant error correction, peer mediation, and a specific criterion (or specific goal of speed and accuracy). If you would like to further explore the specifics of Repeated Reading, I refer you to this posting on the Iowa Reading Research Center’s blog: www.iowareadingresearch.org/sites/iowareadingresearch.org/files/oral_reading_fluency_error_correction_procedure.pdf. Repeated reading of the uncapitalized kind can be young students reading a previously read book during independent reading time or as the first activity in a guided reading group. It can also be choral or echo reading during small group instruction or with a large group during poetry practice. Choral and Echo Reading Choral reading is when students read in unison with the teacher. Echo reading is when the teacher reads first and then the students echo it back. For kindergarten students, the echoing is typically one sentence. To determine the number of sentences for older students, I consider the demands of the text and the abilities of the students. If students need support and sentences are relatively difficult (longer and/or with higher decoding demands), perhaps one sentence will do. But if sentences are shorter and easier to decode, pick two or three sentences to echo back. Otherwise, students with good short term memory will simply “parrot back” a sentence without ever reading it. How To Do Choral and Echo Reading Repeated reading in the form of echo reading can occur in either the whole group or during a small group situation like a guided reading group. When working with students who need a lot of support, I incorporate regular bouts of echo and choral reading. It looks like this:

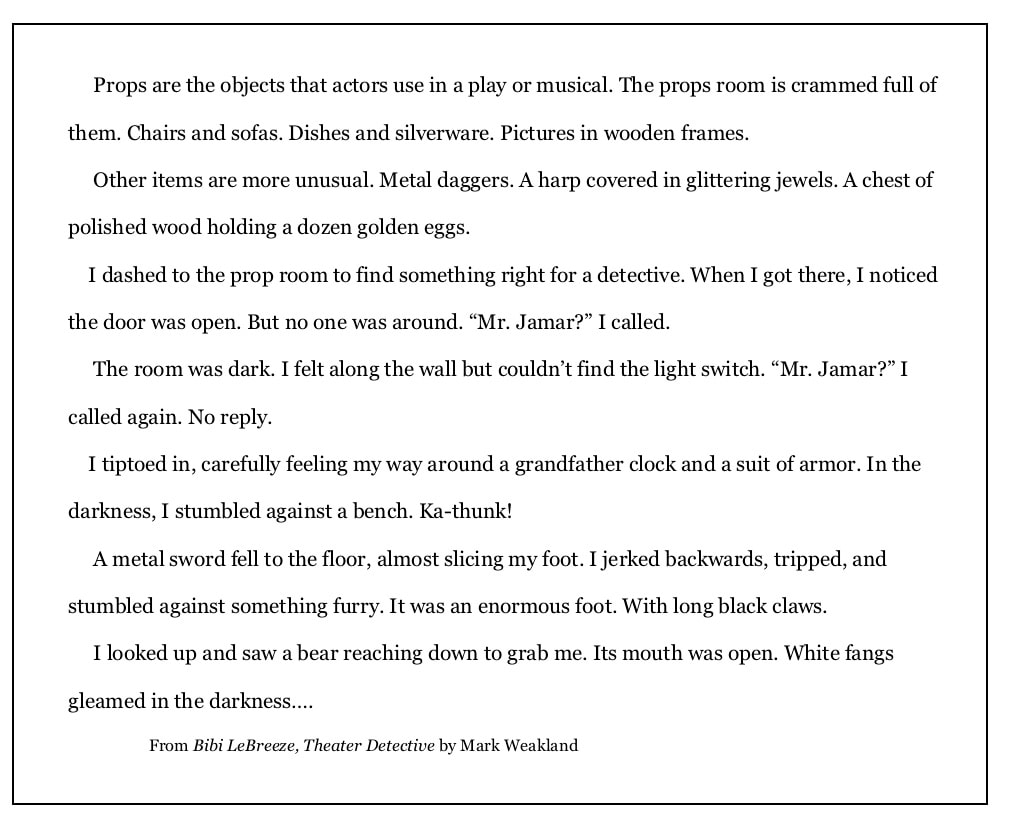

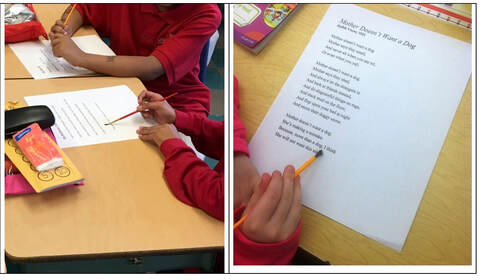

Let's imagine the students have just finished whisper reading this piece of text. Here is what the routine looks like with a 3rd grade guided reading group. Paintbrush re-reading Fluent reading unfolds smoothly, with expression, and in broad brushstrokes of phrasing. To drive the point home, consider putting out a can filled with small paintbrushes. Then allow your students (independently or in small or large groups) to grab a paintbrush and re-read a poem or passage by pulling the brush smoothly below the sentences. It’s a kinesthetic feedback trick that keeps kids engaged as they re-read. Read like a painter, not…like…a…pointer! Fluency is Much More Than Rate

Regardless of whether you use echo reading, choral reading, paintbrush re-reading, or some other form or combination of repeated reading, the students’ goal is always the same: to read the words of the text accurately, at a reasonable pace, and with expression and phrasing that sounds like oral language. Notice that the definition of fluency I gave is much more than rate (or pace) of reading. In “The Great Fluency Rush” that followed the 2000 release of the National Reading Panel’s Report, fluency work was everywhere in schools, assessments like DIBELS and programs like Read Naturally were ubiquitous, and reading rate sometimes became synonymous with fluency. I like to say that “rate was overrated.” In some schools, rate is still overrated! So, I am glad that researchers like Shaywitz and Shanahan, and organizations like the Iowa Reading Research Center, are here to remind us it is important to build accuracy first and not lose sight of expression and phrasing (Shaywitz, 2020; IRRC 2019; Shanahan, 2020). As the IRCC puts it, “Reading quality rather than reading speed.” SOURCES and CITATIONS

Comments are closed.

|

Mark WeaklandI am a teacher, literacy consultant, author, musician, nature lover, and life long learner.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed