|

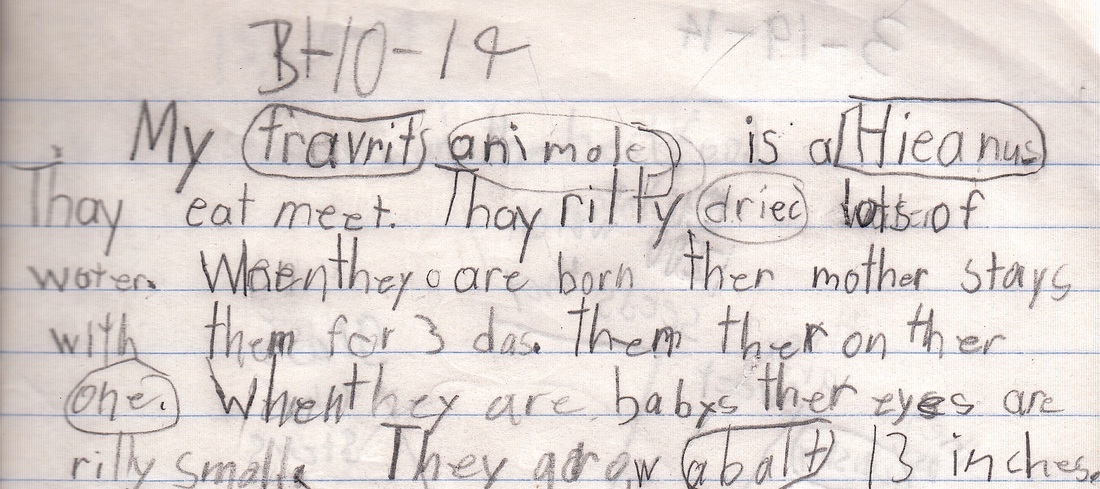

I’ve been thinking a lot about spelling. As a kid, I aced my weekly elementary school spelling tests. But my writing was always peppered with mistakes. This is still true today. I have to stop and think about how to spell rhythmical, I’m likely to write hesitent for hesitant, and when it comes to spelling words like silhouette and lackadaisical, forget it. At times, my lack of spelling ability slows my rate of writing, and yes, it has occasionally embarrassed me in public. Once at a professional development workshop, I was elected to be our group’s scribe. I don’t know how this happened because I have “writinginpublic-ophobia,” but there I was, Sharpie in hand and poster board before me. The group’s task was to list our thoughts on various reading intervention programs. As others talked, I wrote. At one point I wrote “excellerate progress.” When a team member politely asked if I meant to spell the word accelerate, as in “to gain speed,” I replied, “No, I meant to write the other word. You know, the one that means to pick up the pace in a most excellent way.” Through my mid-twenties, I never gave my spelling weakness much thought, and certainly never thought about how others spelled. This changed, however, when I turned twenty-seven and became a teacher. Then, I began to wonder why it was that some children scored a perfect on their spelling test every week but mangled their authentic writing, incorrectly spelling words like they, animal, and meat. I deliberated over the best way to teach spelling to my students, especially those that struggled the most. And I wondered if my spelling instruction was ultimately helping or hurting the reading achievement of my students. As the years went by and I gained experience as both a literacy consultant and a classroom teacher, I became convinced that carefully planned and executed spelling instruction was one of the key ingredients in the recipe for increasing the achievement of struggling readers and writers. And in the last three years, I’ve grown increasingly passionate about spreading the word on spelling instruction –how, when done poorly, it contributes little to improving the reading and writing skills of elementary-age children, and how, when done well, it can enable students to independently solve their spelling difficulties, expand their reading and writing achievement, and foster happiness in teachers and parents because they are more likely to see words spelled correctly in a child’s day-to-day writing.

The type of spelling instruction you engage in can make a world of difference. I believe this especially true for the children who struggle the most to read and write. I spent the bulk of my classroom-teaching career working with low achieving students and I saw them fail when my instruction was ineffective and flourish when my instruction was based on best practice. I am convinced that when you trade traditional spelling instruction for an approach that is developmental, mastery-based, and closely tied to reading and writing, you greatly increase the chance that your students will not only become better spellers, but better readers and writers. Spelling is certainly not the only key to reading and writing success, but it is an important one! Research has pointed to (and continues to point to) ways to teach spelling that are more effective than those given in many traditional basal programs. The most effective spelling instruction is direct and explicit (Levin & Aram, 2013; Rosenshine, 2012), systematic and sequential (Gentry & Graham, 2010), focused (Rosenshine, 2012), differentiated (Invernizzi & Hayes, 2004; Morris et al, 1995), strategy-based (Adams, 2011), mastery-based (Dewitz & Jones, 2013; Invernizzi & Hayes, 2004), centered on sound, pattern, and meaning (McCandliss, et. al. 2015; Moats, 2005; Perfetti, 2009; Graham), based on the theory that spelling is developmental (Henderson, 1990; Treiman & Bourassa, 2000; Levin & Aram, 2013), and intimately linked to reading and writing (Adams, 2011; Gentry & Graham, 2010; McCandliss, et. al. 2015; Reed, 2012). This is not to say that basal spelling programs are none of these things. In fact, they are often systematic, explicit, and rooted in the conventions of English spelling, and they have plans for teaching strategies and differentiation. However, core-reading spelling programs may not be systematic enough. Additionally, their scopes are often too broad (they introduce too many conventions at once) and their instructional sequences go by too quickly and are not based on the philosophy of mastery learning. There are other problems. Basal-based spelling programs may lack explicit links to reading and writing, or the links may be weak. Traditional spelling programs present “everything under the sun,” but fail to explicitly point out what concepts and activities are most important. When the expectation is that everything presented in the manual will be taught and completed (because your district expects fidelity to the basal program), then instruction is diluted and academic gains may be diminished. More becomes less. Also, teacher manuals may fail to emphasize or even mention easy to implement and highly effective instructional practices, such as the consistent use of direct and explicit instruction or having kindergarten and first grade children look at and then say the teacher-provided correct spelling of their invented spelling (Levin & Aram, 2013). Finally, traditional programs may underemphasize mastery learning, student self-monitoring, and the utilization of spelling strategies, as well as the adoption of a developmental stance in which strategies are taught to children if and when they need them. To transform a traditional spelling program into one that incorporates the best practices identified by research, it may be helpful to think of the transformation as a process that takes place over time, step by step. As seven is a magic number and I once wrote a kid’s song called “Take a Peepy Step,” I thought it made sense to describe this transformational process as a series of seven steps. Here they are: 1. Understand: That the alphabetic principal is foundational to spelling; that to teach children how to spell one must teach them to be strategy users; that sound and meaning lie at the heart of spelling instruction; that spelling is intimately connected to reading and writing; and, that spelling is developmental. 2. Assess: Assessment begins at the beginning of the year with spelling inventories, writing sample analysis, and reading assessments, and it continues in a formative way throughout the year; assessment is essential for understanding where students are on a developmental spelling continuum, as well as for differentiating instruction; formative assessment occurs through weekly quizzes, notes on spelling word work, and writing samples that provide data for future instruction. 3. Step Back: To paraphrase novelist Erika Taylor and spelling guru Marcia Invernizzi, step back to move forward. Assessment shows that students exist in groups on a continuum of spelling development. This is the first step back from a program that whisks kids through a rapid and unwavering spelling sequence and a weekly regime of memorize, test, and move on. Other important ways to step back include stepping back to focus your spelling list, stepping back to slow down the rate at which you move through your spelling sequence, and stepping back to teach to mastery, especially with young children who must master the essential conventions of syllable spelling, starting with short vowel words and closed syllables. 4. Teach: Teach children how to spell, not what to spell. This includes helping spellers become metacognitive so that they know that not all of their words are spelled correctly and they know how to fix up their mistakes. This also includes teaching children that sound and meaning are at the heart of spelling and giving children strategies that they can use to spell unknown words and decode unknown text. 5. Bring: Step Five is the process of bringing in more words. These words follow the pattern or patterns of a re-focused lesson. When a pattern is manifested through the study of many words, children have the opportunity to achieve pattern awareness. More words also enable more word work activities. Finally, bringing in more words helps us to more easily differentiate for two or three groups of students. 6. Build: Build opportunities for spelling application, through prompts that speak to the Common Core writing standards, but more importantly through authentic writing activities, through writing that is connected to reading, and through writing that is connected to other subject areas. Opportunities for spelling can also be built into small and large group reading instruction. 7. Refine. Refine your instructional techniques, in service to spelling but also in service to any literacy lesson. When we use more explicit and direct instruction, modeling, intentional language, and positive reinforcement, our instruction is more powerful and our lessons are more effective. And when, through professional development and the integration of technology, we refine our spelling instruction within and across grade levels, we can truly say we have transformed our school’s spelling program. Comments are closed.

|

Mark WeaklandI am a teacher, literacy consultant, author, musician, nature lover, and life long learner.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed