|

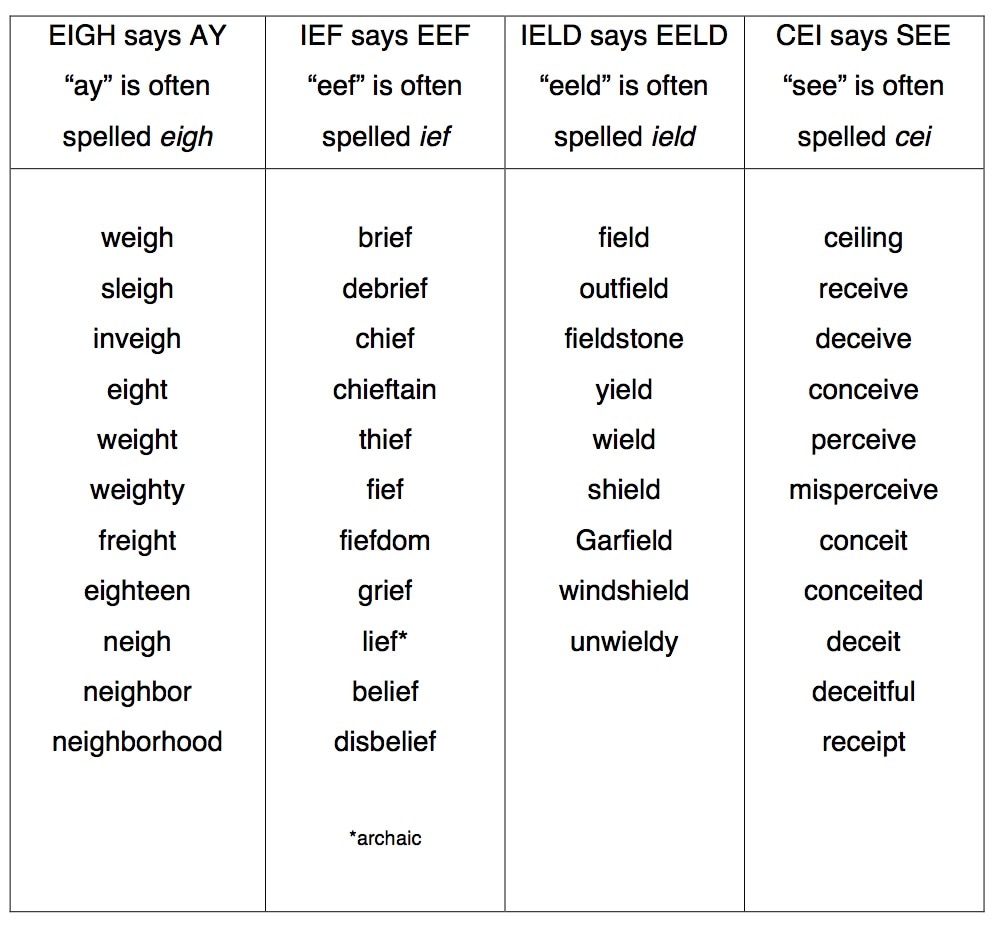

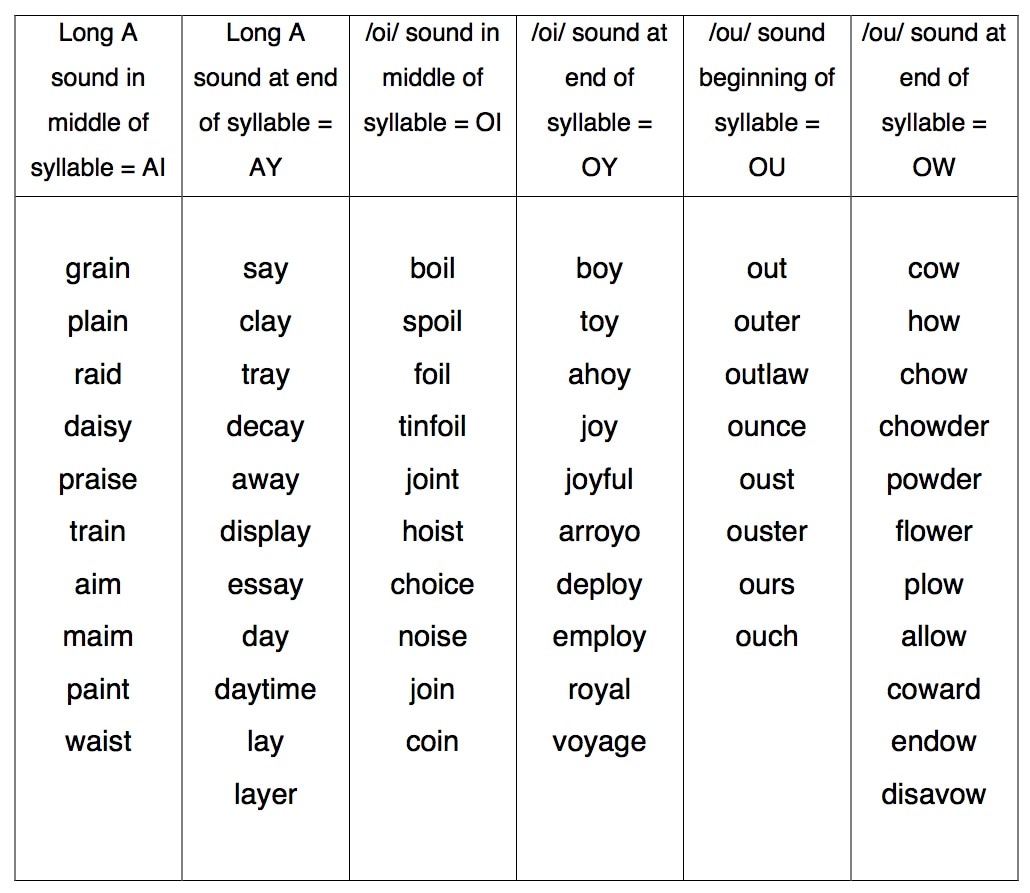

If you’ve been following my spelling posts, you’ll know that for the last year I’ve been encouraging teachers to teach students how to spell, not what to spell. Teaching how to spell means moving away from a one-size-fits-all program and towards a philosophy of differentiation. It means showing kids how to think about words by teaching lessons focused on sound, pattern, and meaning. It means teaching students strategies that they can use to spell unknown words. And it means teaching broadly applicable principles of spelling, rather than dozens of narrowly applicable spelling rules. Simply said, spelling rules do little to help children understand how words work. When they have numerous variations and exceptions, they can’t be applied to unknown words. Finally, traditional spelling rules can lead to confusion and spelling errors. Consider these two popular rules: “I before E except after C,” and “When two vowels go walking, the first one does the talking.” “I before E except after C” only applies to words in which the ie combination functions as a vowel digraph that clearly makes a long E sound. For example, the following words can be spelled using I before E: piece, niece, chief, thief, yield, and field. Meanwhile, the words deceit, ceiling, and receive provide the exception to the first half of the rule. But in dozens of other words, the rule fails more than it succeeds! For example, I before E does not work in words such as weigh, sleigh, eight, freight, beige, and vein, or in words such as foreign, forfeit, heifer, and height. Nor does it apply to words in which an adjacent I and E (or E and I) aren’t a digraph, such as in deity and science and their various derivations (deify, deification, prescience, scientific, and so on). Finally, even when a vowel digraph makes the long E sound, there are exceptions to “I before E” Here I am thinking of seize, weird, either, neither, protein, and caffeine, among others. In the end, because “I before E” has so many exceptions, it is rendered mostly useless as a rule. If you want to teach children how to determine if they should have the E first or the I, I’d suggest you start with a broadly applicable principle: certain vowel team patterns are almost always pronounced the same way. This means you should teach the eigh pattern because it almost always says Long A (sleigh, weigh, eight, weight, neigh, neighbor), you should teach the ief pattern because it almost always says EEF (thief, grief, brief, debrief, belief, disbelief), and you should teach the ield pattern because it almost always says EELD (field, yield, wield, shield, Garfield, windshield). Teach your students these patterns and then give them many opportunities to spell, write, and read these patterns in many different settings. The more they spell, read, and write words with patterns, the more they will enter these words into the dictionaries in their brains.  Now let’s consider “when two vowels go walking, the first one does the talking.” Like “I before E except after C,” the “two vowels go walking” rule does little to nothing to help students develop an understanding of spelling patterns within words. How does it teach kids to read or spell the following words, all of which have “two vowels walking:” vein, great, height, their, spread, spoil, pear, noun, piece, heard, rough, and moon? Why not teach this much more useful principle: a sound’s position often determines its spelling. Often, there are many spellings for one vowel sound. Thus, vowel spellings can seem horribly complicated. But when you teach students to be guided by sound position, vowel spellings become more predictable. For example, the /ou/ sound can be spelled ou or ow. Before students have committed whole words like cloud, clown, outer, and flower to the dictionaries in their brains, they need a way to decide how to spell the /ou/ sound. Is it clowd or cloud? We can help kids figure out which spelling to use by teaching them to think about where they hear the sound in a word. In this instance, you might tell your students that if the /ou/ sound is heard at the beginning of a syllable, spell it ou. Then give them examples (ouch, out, oust, and ounce). If /ou/ is heard at the end of a syllable, spell it ow (as in cow, now, chow, eyebrow, powder, and flower). And if /ou/ is in the middle of a syllable, use ou (as in mouse, loud, bounce, joust, and grouch). Finally, teach them an exception to the middle position: if you hear /ou/ in the middle of a one-syllable word and the vowel sound is followed by a /n/ or /l/ sound, then spell it ow (as in brown, gown, howl, and growl). Other vowel spellings that can be determined by sound position include oi and oy, ai and ay, and long vowel sounds at the end of a syllabe in multi-syllable words (most are open syllables, which are simply spelled with one vowel, as in hero, ego, fever, ivy, vital, pilot, navy, favor, bacon, radio, and potato). Using the position of a sound in a word also works for consonant spellings. Thus, when you hear the /f/, /l/, or /s/ sound after a short vowel sound in a one-syllable word, you double the f, l, or s letter (as in fluff, bill, and glass). The main point: a few principles are easier to remember and more broadly applicable than many exception-ridden rules. Comments are closed.

|

Mark WeaklandI am a teacher, literacy consultant, author, musician, nature lover, and life long learner.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed