I was contacted recently by a Title I coordinator with a question: “What is meant by real, connected text?” The coordinator, currently working with her teachers to research and then restructure their district’s reading interventions, asked the question with regards to a point made by David Kilpatrick in his 2015 book, Essentials of Assessing, Preventing, and Overcoming Reading Difficulties, namely, and I’m paraphrasing here, that effective reading interventions share the following:

Because reading research tells us “the components of effective reading instruction are the same whether the focus is prevention or intervention” (Foorman & Torgesen, 2001), we know Kilpatrick’s trio is just as important to classroom reading instruction as it is to reading interventions. But what, exactly, is meant by real, connected text? How much time should students be given to read it? And in what settings are the various types of text appropriate? I’ll tackle the first question this week and the last two later in August. What is real, connected text? Defining educational terms is challenging. Our field seems to constantly create, redefine, and deconstruct its vocabulary but rarely discards any of it. Still, I’ll try to give a definition, starting with the “connected” part of the phrase. I take connected to mean multiple sentences, contiguous on a page or presented over pages, relating to each other in ways that ultimately tell a story or present cohesive information. These sentences, a.k.a. connected text, can be found in:

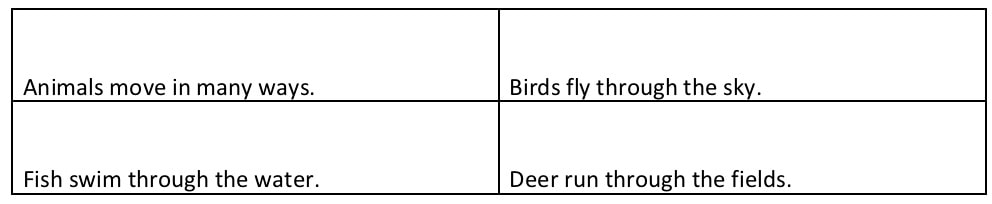

Authentic text Unlike the term “real text,” authentic text has been repeatedly defined by others. Here’s what the Florida Department of Education, which says: “Authentic text may be thought of as any text that was written and published for the public… written for “real world” purposes and audiences: to entertain, inform, explain, guide, document or convince” (FLDOE, 2020). Educators like Scott Thornbury and Lesley Morrow also weigh in, saying “…text is authentic if it was originally written for a non-classroom audience” and “[authentic text is a] stretch of real language produced by a real speaker or writer for a real audience and designed to convey a real message” (Thornbury, 2008; Morrow, 1977). An example of text most would classify as authentic is Nancy Shaw’s entertaining Sheep in a Jeep, a picture book featuring simple sentences of varying structure; colorful, active illustrations; a plethora of phonic patterns; and a variety of engaging verbs (go, yelp, push, grunt, shove, leap, splash, thud, shout, cheer) which provide the reader with, as Catherine Snow puts it, “rare and sophisticated” vocabulary. Although teachers and parents can use this text to expose children to language and teach concepts (sequence, verbs, using context to gain meaning, and so forth), the book was not originally written with teaching in mind. Definers of "authentic text" often go beyond books to classify blogs, novels, pop songs, newspaper articles, recipes, and road signs as authentic. Some also include radio shows, podcasts, photos, and video clips as examples. For me, podcasts and video clips won’t contribute much to teaching students the fundamentals of how to read written words and so I’ll put them aside. And while environmental text certainly helps children understand that text is an integral part of the world, I don’t think it is a central tool of K-3 reading instruction. So, in the end, I define connected, authentic text as text 1) that features connected sentences over one or more pages, 2) is not created for instructional purposes, and 3) is one of the main tools for fundamental reading instruction, K-3. Varieties of text that work within this general definition are poems and rhymes, picture books of all kinds, and chapter books, simple and more advanced, both narrative and informational. Once again, many of these types of texts can exist in digital format although I think the science of how well digital text works to teach reading is still in its infancy (and there are many unanswered questions). A broader definition of “real and connected” My sense is that Kilpatrick’s real and connected is a bigger category than authentic. Thus, in the file drawer labeled "real and connected," I’ll include books written specifically to help children learn how to read. Here I am thinking of the leveled books and predictable (pattern) books often used in kindergarten and 1st grade instruction. Leveled text Unlike authentic text, leveled readers are written with instruction in mind. Typically they support young readers with controlled vocabulary, a measured number of words in a sentence, and sometimes a repetitive sentence structure. For example, the first four pages of an early leveled reader might be this:  These types of books also fold in supports typically associated with picture books, such as photographs and illustrations. Also like authentic books, these texts present children with multiple, relating sentences in a book form (with title, cover art, and illustrations) that often tells a story or gives topical information. Finally, I’ve found that young children are excited when they finish one of these contrived texts and the excitement that springs from their reading success is a very real thing.  Text written with teaching in mind Other pieces of text I categorize as “real and connected” are the informational articles and short, fictional stories found on sites like Readworks.org. Specifically authored for a website or program, these passages are written with reading levels and teachable content in mind. Like leveled readers, they typically have measured vocabulary loads, controlled sentence structure, and confined sentence lengths. Even with their constrained writing, these informational passages and short stories seem real to me (and almost authentic) because they closely follow text forms (newspaper articles, short stories in magazines) that are written without instruction in mind. Is decodable text real? Writers create decodable text with a narrow teaching focus in mind: giving beginning readers practice in breaking the code through carefully constructed sentences that use a small number of phonic patterns. The construction of decodable text consistently points students towards the strategies of “look at the letters,” “look for patterns” and “sound out the word.” This is why decodable sentences and paragraphs are an important part of many curriculums, such as Barton Reading and Wilson Reading among others, that aim to help students who have dyslexia. By using a limited number of phonic patterns, decodable text gives students who need it more repetition and distributed practice in phonic decoding, and fosters literacy development by helping beginning readers build detailed and accurate replicas of patterns and words in neural circuitry (Shaywitz, 2020; Duke, 2019).  Because decodable text is written by authors who use very narrow parameters to accomplish a specific task, some may see it as the opposite of real or authentic. But I’d say it becomes more real and authentic if it makes sense as a story and builds topical, background, and vocabulary knowledge (Hiebert, 2020). In my mind, the best example of highly controlled text that is real, connected, and perhaps even authentic is Dr. Suess’s Green Eggs and Ham. After using only 225 different words to tell the tale of The Cat in the Hat, Suess’s editor bet him he couldn’t write another book using fewer. He did, using only 50 words to write Green Eggs and Ham. A classic in the world of children’s literature, this highly controlled text features memorable characters, humor, conflict, resolution, and character growth. Use it all to read, read, read In the end, all of this might be mere semantics. The big idea is to get kids to read, read, read! No matter what text you have available, do your best to program opportunities for children to read. It's best when students are reading everything and anything, from traffic signs and recipes to poems, website articles, graphic novels, and picture books. Give more support for those who need it. For example, if some students need more practice in breaking the code, give them additional opportunities to read decodable text. But don’t forget to also give them rich, authentic children’s literature. Support all students through read alouds and a kick butt classroom library laid out in browsing bins. No one type of text will teach all children to read and certainly you can’t teach all children with only one reading textbook! In my next blog I’ll discuss programming time to read all types of text, every day and for long periods of time. Sources / Citations

Comments are closed.

|

Mark WeaklandI am a teacher, literacy consultant, author, musician, nature lover, and life long learner.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed