|

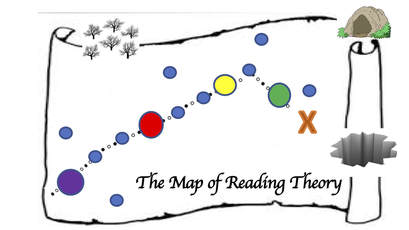

As I prepare to travel to ILA’s 2018 Conference, maps are on my mind. I’ll use a mental map to get from my home in the hinterlands to the Pittsburgh Airport. Knowing the roads of western Pennsylvania well, I have no need for Google or Apple maps. But in Austin, I’ll use my phone to navigate from my BnB to the convention center, as well as to the parks, Tex-Mex eateries, and music nightclubs I plan to visit. Finally, I’ll use a digital or even a hardcopy map of the conference center to get to Room 18 D (where Carrie Zales and I will present our session, Literacy Crosswalks for Leaders). I am fascinated by maps. Always have been. Perhaps this is the reason I am using the image to create an analogy for how literacy leaders can create stronger reading, writing, and spelling programs. For the last four years, as part of my business, I have provided workshops, consultation, coaching, and model lessons to teachers and administrators in school districts. With regards to literacy instruction, my starting point is always reading theory (as formulated by research) and the instructional best practices that spring from that theory. In a Reading Today blog last year (as well as in this blog), I called our theoretical understanding of reading The Map. Now, I’d like to expand upon that image and idea. The idea of a scientific theory being a map was put forth by author and researcher Peter Godfrey-Smith. Science is largely about finding patterns of behavior – the behavior of quarks and atoms, of elements in a chemical reaction, of children interacting with text. These patterns are observed over and over again in a variety of situations. In time, facts are identified and general laws are formulated. Godfrey-Smith says that a theory of science (a.k.a. a map), is a descriptive narrative of how a particular system works. A map (a.k.a. theory of science) shows what is essential, focuses the map reader on the core properties of the considered system, and perhaps most importantly, is predictive. When it comes to literacy, The Map of Reading Theory describes reading as landscape features (scientific facts). These features include, but are not limited to, the alphabetic principle, metacognition, speech as a starting point for reading development, fluency as rate and accuracy, the idea that encoding and decoding draw from the same pool of knowledge, the understanding that the brain reads through the coordination of various processing systems including semantic, orthographic, and phonological, and so on and so forth. Each feature on The Map of Reading Theory can be used to plot a path towards an ultimate destination point (X). For teachers and parents (in fact for everyone), this destination point is capable and happy readers and writers. Because The Map is highly predictive, if educators follow it, there is an excellent chance they will get their kids to X. To continue the analogy, the most efficient path to X (capable and happy readers and writers) involves transecting specific map features. These features sit within larger circumscribed areas. I think of these larger areas as the frameworks of reading, writing, and spelling instruction. Consider the following:

The list of features, as well as the areas that circumscribe said features, would fill a book. In fact it fills many books, including the 2.6-pound, 1,344 page-long book Theoretical Models and Processes of Reading, 6th Edition that sits on my desk (published by the International Reading Association). As I interact with principals and teachers, my desire is for them to follow The Map of Reading Theory- always! Following it greatly increases the chance that students will become successful readers, writers, and spellers. Of course, some paths are more direct (efficient, effective) than others. The more a child struggles, the more you should chart a direct course. But even then, multiple pathways to success exist. Multiple pathways, however, does not equate to all roads being equal. Some pathways are simply too circuitous and convoluted. Others are downright dangerous. What is to be avoided at all costs is a path that veers to the fringes of the map or worse, off the map entirely. Uncharted and dangerous “features” include the Pits of Unproven Practice (teaching to individual learning styles; using tinted lenses to “help” children with dyslexia ), the Thickets of Instructional Ignorance (discovery learning is best for all; writing spelling words five times each is an effective way to practice), and the Caves of Classroom Isolation (“Our district doesn’t use literacy leadership teams or coaching” and “I close my door and keep my head down”). These are places we don’t want to go! There are, however, more maps to consider. If reading, writing, and spelling success is going to be scaled to a point where it occurs throughout a district (beyond the individual classrooms of highly capable teachers), then it is necessary to follow other maps as well. What are these other maps? I’d say:

In Part II of this blog (which I hope to publish by the end of this week), I’ll define these maps and tell two personal stories regarding them. Comments are closed.

|

Mark WeaklandI am a teacher, literacy consultant, author, musician, nature lover, and life long learner.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed