|

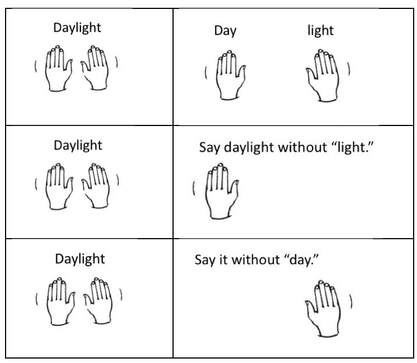

For decades, the educational community has known of the importance of phonological awareness. Many researchers pointed it out prior to 2000 (Bradley, L. & Bryant, 1983, Stanovich, K.E. & Siegel, L.S., 1994, Ehri, L.C., 1998), but it really moved front and center when the National Reading Panel report named it as one of the Five Big Ideas of Reading. The Panel said that teaching phonemic awareness not only helped preschoolers, kindergartners, and 1st graders learn to read, but also helped older readers with reading problems. (NICHD, 2000). Since that time, reading researchers like Sally Shaywitz (2003/2020), Maryanne Wolf (2008), David Share (2011), and Mark Seidenberg (2017) have been highlighting the research on and importance of phonological and phonemic awareness. Here’s Seidenberg talking about it in his book, Language at the Speed of Sight: “For reading scientists, the evidence that the phonological pathway is used in reading and especially important in beginning reading is about as close to conclusive as research on complex human behavior can get” (p. 124). In his 2015 book on preventing and overcoming reading difficulties, David Kilpatrick spotlighted phonological and phonemic awareness within intervention programs, saying that the especially effective ones "…aggressively address and correct students phonological awareness difficulties and teach phonological awareness to an advanced level” (Kilpatrick, 2015). Robust teaching is critical to the development of orthographic mapping: if children cannot analyze and discriminate between the individual sounds of a language, it is very difficult for them to assign letters (alone or in combination) to each sound, and if sound-symbol associations are not mastered, reading and spelling cannot develop. Kilpatrick also mentioned a study that shows how “training in phonological awareness and letter-sound skills reduced the number of struggling readers by 75%” (Shapiro & Solity, 2008). But why wait until students are struggling to teach phonological awareness to an advanced level? To prevent reading difficulties, let’s teach advanced sound analysis skills in regular education classrooms at the Tier I level. What follows are classroom activities that begin moving young students towards advanced phonological awareness. The first focuses on large chunks of sound – syllables. The second has to do with the smallest bits of sound – phonemes. Hands Together, Apart, and Away Advanced phonemic skills include adding, subtracting, and substituting phonemes to make new words out of existing words. Set the stage for this by teaching students to delete or add larger sound chunks such as syllables. One practical way to do this is to practice the deletion of one word in a compound word. Then, practice a more advanced version by replacing the deleted word with another word, thus forming a new compound word. To help children better understand how these deletions and additions work, use hands together, apart, and away. To do this activity with hand motions and preserve “reading left to right,” you’ll need to turn your back to your students and present the back of your hands. With your hands together, thumb touching thumb, say a compound word like “Daylight.” Pull your hands apart and say the compound word as separate words: “Day, light.” Next, put your hands back together and say, “Daylight.” Then, ask your students to say daylight without day. Model taking away your left hand and gently shaking your right. If they don’t know the remaining word, say, “Light.” Ask your students to say daylight without light, taking away your right hand and gently shaking your left. If they don’t know the word, say, “Day.” Here are other words to say as you move your hands to show syllables and syllable deletion:

An advanced form of Hands Together, Apart, and Away is not using hands at all! Bump up to an even higher level by using three syllable words. At this point you will definitely give up the use of your hands to segment syllables (unless you are an octopus). Have students say a three-syllable word like November. Then ask them to say only the first syllable, the last syllable, or the middle. A more advanced version is to ask them to say the word with a syllable deleted. For example, “Say November without the No.” (Vember) Or say, “Say November without the last syllable.” (Novem). Stretch and Zap the Word. Then go beyond! Sound stretching helps students hear the individual sounds of a word. Later they can segment the phonemes more discretely by zapping out the sounds., Use the I Do, We Do, You Do sequence to first model the action and then have students practice.. To stretch a word, tell your students to imagine the word as a big rubber band. Or if you live in western Pennsylvania, tell them to imagine a “gum band.” They’ll know what you mean. Grab hold of either end of the word (make two fists and hold them close to each other in front of you). Then slowly pull your hands away from each other, stretching the word out, holding out the vocalization of each phoneme as you stretch. After the rubber band is stretched as far as it can go and all of the phonemes have been drawn out, snap the band back together with a handclap. When students clap, they say the word. In this way, phonemes are brought back together to make a word. For example, flip would be modeled ffff-llll-iiii-p, (clap) flip! And dream would be d-rrrr-eeee-mmmm, (clap), dream! Some teachers teach this technique as “bubble gum words,” stretching the word out from the mouth as they were stretching a wad of chewed bubble gum. Is this disgusting? Perhaps. But if kids are engaged, do it. We do whatever it takes to get students to learn, right? Second graders stretching a word Add zapping to the stretch routine to help students phonemically segment words and feel that segmentation in their bodies. To model zapping, first say the target word as you make a fist. Next, segment the word into the sounds you hear, pumping your hand and throwing out a finger for each sound you say. For example, the word it gets two pumps. The index finger comes out when you say /i/. The middle finger comes out when you say /t/. Finally, draw your fingers back into a fist, blending the sounds together, and saying the word - it! When giving words, it is important for you to say the word and have your students repeat it with you (I Say, We Say) before the zapping begins. I Say, We Say gives a model of the correct pronunciation of the word prior to sound segmentation and an opportunity to repeat that correct pronunciation. After all, one cannot segment phonemes correctly if the word isn’t pronounced correctly. Here is an example of a teaching routine I ran in classrooms. If I used a total of six or seven words, it took about five minutes. My instruction was direct and explicit, used modeling, and proceeded at a brisk pace. The point was to work in lots of practice so the kids could master the technique. Once mastered, children can use zapping as an independent strategy for spelling and reading unknown monosyllabic words. In this lesson, we’ll imagine the teacher is working with a group of second graders on the r-controlled syllable.

With short bursts of repeated practice distributed over time, students can master the art of stretching and zapping in just a few weeks.Then they will be ready for more advanced work: sound identification and sound deletion. For example, after students have segmented stork as /s/ /t/ /or/ /k/, ask, "What is the first sound?" The answer should be /s/. Then ask, "What is the final sound?" and "What is r-controlled sound?" The answers are /k/ and /or/. Sound identification is a more advanced form of phonemic analysis than simple segmentation.

Finally, ask students to delete a sound. For example, and once again using stork as the target word, ask your students to "Say stork without the /s/." The correct response is /tork/. Then ask them to "Say stork without the /k/." The correct response is /stor/. Sound deletion activities are a great way to build advanced phonemic awareness. They also have the added benefit of being sensitive to some types of reading difficulties. This means that sound deletion tasks can provide clues as to why a child is having a difficult time learning to read and write, and here I am thinking of students who have dyslexia due to phonological processing impairments. One last thing: if you prefer to use a program, and you are looking for effective, low-cost options, here are three excellent resources:

SOURCES

Comments are closed.

|

Mark WeaklandI am a teacher, literacy consultant, author, musician, nature lover, and life long learner.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed