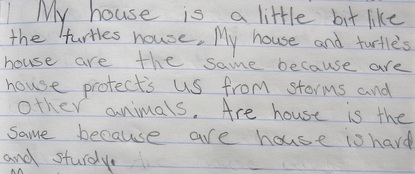

An amazing amount of work teaching in schools near and far, bikes ride in the fabulous fall weather in times between the work, and a recent bout of bronchitis - all of this has kept me from my blog. But today I’m back, breaking the dry spell with an entry on spelling strategies. In a September post, I discussed the sound-based spelling strategies of Stretch, Zap, and Chin Drop. I followed that with a post on an activity that gives children opportunities to practice these sound-based strategies. Today’s post has to do with meaning, the third layer of orthography (sounds and patterns being the other two), which begins to develop a little later in a child’s life, typically around the age of 6 or 7. Just as words have sound parts (phonemes) and letter parts (graphemes), words also have meaning parts (morphemes). Teach morphemes to students and they can use meaning to spell words. One-syllable words are often morphemes unto themselves. Think of words that rhyme or sound similar, words such as two and too and our and are. While they sound similar, their meanings are dramatically different. Even at a young age, students can be taught to pay attention to the meaning of these words. But the initial teaching must be direct and explicit, and for some children the opportunities for practice must be many. Below we see a third grader who is confused about the usage of the words are and our. The third grade teacher, who happens to be me, never gave his class enough opportunities to practice the use of both words, so I’m not surprised that this third grade writer didn't use the word correctly in this independently written piece. As an instructional guru once said, “If they didn’t learn it, you didn’t teach it!” By the way, formative assessment through independent writing samples (such as this one), provide opportunities to change instruction In the upper grades of 4th, 5th, and 6th, affixes and Latin roots take center stage in spelling, and it’s at this time that teaching children to pay attention to meaning really begins to pay off. Most upper grade elementary school teachers I know spend a good deal of time teaching students prefix and suffix meanings, such as un (not), uni (one), less (without), and so on. The more time you spend on the spellings and meanings of affixes, as well as the spelling and meanings of roots, the more your students will understand the meaning of the text they are reading. Exploring Latin (and Greek) base words and root words helps students understand that word spellings hold word meanings. In the upper grades, spelling instruction shares much with vocabulary instruction because so much of it is meaning based. By examining the spellings of seemingly unrelated words, children can begin to see how and why they are actually related to one another. For example, astro and aster have their roots in astron, the Greek word for star. Knowing the morpheme aster helps readers understand the meaning of astronomy, astronomer, aster (the flower) and asterisk. But what about disaster? Disaster, a word that literally means bad star, is rooted in the ancient belief that comets (once thought to be stars) were harbingers of bad news. When a comet appeared, war, pestilence, or some other calamity was sure to follow. Here’s an interesting connection between common words based on the root quar. We all know a quart is a fourth of a gallon, a quarter is a fourth of a dollar, and a quartet has four members. But what’s quarantine’s connection to four? Turns out that quarantine comes from quarante or quarania, the French and Italian words for 40. In the days of sailing ships, if a vessel arriving in port was suspected of harboring an infectious disease, the ship and its sailors had to avoid contact with others by staying moored off shore for about 40 days. Paying attention to meaning can be especially helpful to spellers because the sound (but not the spelling) of a morpheme can change between words. If students understand that know is spelled k-n-o-w, and if they realize that the word knowledge has a meaning related to know, then they can use that information to correctly spell the word knowledge, even when the words initial vowel sound is different from the vowel sound of know. The same holds true for word derivations such as pray and prayer, define and definite, wild and wilderness, and relate and relative. I use the “think about meaning” strategy fairly frequently. For example, because I have a hard time seeing the word competition in my mind, sometimes I’ll spell it compitition. But as soon as I write it, I can see that this word doesn’t look right. If I can remember to start my spelling process by thinking of the word compete, which is easy for me to see and spell, then I spell competition correctly right from the start. The spellings of roots and bases often remain stable across word derivations, even as the sound of the roots change. Using meaning to spell is also like spelling by analogy. In effect, students can use a word they know to help them spell a word they don’t know. As before, teach your students a little routine for spelling an unknown word by meaning and analogy: 1. Say the long word you want to spell out loud. Think about what it means. 2. Ask yourself, “Is there a shorter word that is related to the meaning of this word? Do I know of a short word that would help me spell this longer word?” 3. Write down the short word you know. Use it to spell the longer word. Check the word after you spell it: Is most or all of the spelling of the short word contained in the longer word? Does your longer word look like it’s spelled correctly? 4. Check the word after you spell it: Is most or all of the spelling of the short word contained in the longer word? Does your longer word look like it’s spelled correctly? Comments are closed.

|

Mark WeaklandI am a teacher, literacy consultant, author, musician, nature lover, and life long learner.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed